announcing the Capriccio sopra un tema della Niobe di Pacini, Op. 22, for cello solo

This article is an expanded version of the Editorial Notes that can be found in the published edition, available digitally at this link, and as a physical book here. A video of this piece played by the incredible Antonio Meneses can be watched here.

EDITORIAL NOTES

A mystery unsolved?

Carlo Alfredo Piatti (1822—1901) is widely known for his Twelve Caprices for cello solo, Op. 25, composed in 1865 and published in 1874. Among all his generous production, he composed only one more piece for solo cello, published in 1865 by Ricordi in Milan: a Capriccio sopra un tema della Niobe di Pacini, Op. 22.

Preparing this edition has required a fascinating investigation, since so little is to be found about the piece in the available biographies. The opera that inspired Piatti was Niobe, a heroic-mythological drama in two acts composed by Giovanni Pacini (1796—1867), a prolific opera composer of Sicilian origin, in 1826. The original manuscript of the opera’s full score is held in the Conservatorio S. Pietro a Majella in Naples and has been recently digitised, albeit at such a low resolution as to make it illegible. In the Ricordi Historical Archive one can find only a handful of arias published for voice and piano in 1826-7, but no trace of the full score, nor of parts, or of a complete vocal score. A modern edition doesn’t exist, nor does a complete recording, a true pity for a piece which appeared to enjoy such popularity at the time. Unless, this may have been intentional.

Thanks to the generous and masterful contribution of M° Fabrizio Capitanio, librarian and curator of the Biblioteca Musicale “Gaetano Donizetti” in Bergamo, it was possible to shed some light on this mystery. In the XVIII-XIX century, the full score of an opera existed only in its autograph form but wasn’t usually published, nor used for the performance. If a theatre wanted to schedule a performance, the score would be used as a source by the copyist(s) tasked with preparing the performance material (i.e., the parts). The concertmaster (1st violin) would then head the performance, since the practice of having a conductor was just dawning.

But why not publish an opera’s full score? Simple: there was no market for it, and they knew it very well. The XIX century’s market was focused on amateurs, in the most positive acceptation of the word, that is, those who love doing music but are not professionals. Right after an opera’s première, a publisher would be there to gauge the reaction of the audience to the different arias, and decide which ones to arrange for voice and piano. With a first performance on November 19th, 1826, and five arias and a chorus published by Ricordi between 1826 and 1827, this checks with what M° Capitanio said1.

Plenty of references to the piece can be found, especially as a source of paraphrases, fantasias, and caprices. The most relevant one is undoubtedly the Grande fantaisie sur des motifs de Niobe, S419, for piano, by Franz Liszt (1811—1886), composed in 1835-6. There is also a Grand Duo Concertant for violin and piano, by virtuoso pianist Henri Herz (1803—1888), and a Fantasie for cello and orchestra (or string quartet, or piano), Op. 51 by Friedrich August Kummer (1797—1879), both composed before 1840.

What do all of these have in common? They chose the same aria, showing how that quickly became the most popular excerpt of the opera. The excerpt used by Liszt, Herz, Kummer, and then Piatti, is the cavatina2 “Il soave e bel contento”, with the aria “I tuoi frequenti palpiti” as its second section. Within the musical structure of the opera, this comes from the 3rd scene of Act 1, and features Licida (prince of Thessalia, tenor) following the opening chorus “A’ verdeggianti allori”. Here’s an excerpt of the original cavatina in a vocal score (piano reduction):

My main concern has been to try to understand where Piatti may have heard this opera performed, or whether he had ever played it in the orchestras where he was principal cello—first in Bergamo, and then in London. Once more, M° Capitanio came to the rescue, remarking how this information may have been totally irrelevant. Given how the sheet music market worked at the time, the most plausible hypothesis would be that Piatti got his hands on a copy of the voice and piano reduction, liked it, and decided to compose the Capriccio over it.

But how to verify this? Thanks to an in-depth research of the documented representations of this opera, only one is found: November 19th, 1826, which coincides with the date of the first performance. As astonishing as it may sound, it appears that this opera was never performed again after the debut. Thinking of a possible mistake, I researched other operas by Pacini, and found plenty of performances, both before and after 1826, in Italy and abroad, confirming how unlikely it is that Piatti heard or played the opera in its full form.

Should any more information be unearthed in the coming years, I will update this edition in the next print, and in its digital version available online.

Piatti’s contribution

The origin of this piece may be much older than its first publication, though. Before moving to England in 1846, when he was appointed principal solo cello of the Opera orchestra of Her Majesty’s Theatre in London, he tried to embark into a concert career by touring Europe. One of the surviving documented concerts happened in Pešt—one of the two original parts of today’s Budapešt, Hungary—on August 25th, 1843, after which he fell ill and was even forced to sell his cello. In this concert, he played the Capriccio sopra un tema della Niobe di Pacini, showing how the piece had already been composed by then. His first published opus number (L’abbandono, Op. 1, for cello and piano) dates from one year before that (1842) with editor Francesco Lucca, so we currently do not know why he waited more than twenty years to offer this piece for publication. Ricordi has not saved a copy of the original autograph used to create the first printed edition, which may therefore be assumed to be lost.

He then moved to London, where he played—among the rest—in the première of Giuseppe Verdi’s I Masnadieri (1847), in which a solo line was specially written for him. Piatti lived in London until his retirement from the public concert scene in 1898, before coming back to Le Crocette near Bergamo to spend the last three years of his life.

His rendition of Pacini’s melody is more original and subtle than those by his colleagues’. Where they plainly stated the theme at the beginning, Piatti chose to start with a cadenza-like introduction followed by two pages where the theme is hidden among arpeggios and left-hand pizzicati. As a true gentleman, though, Piatti underlines the motive with emphases:

Above the title, there’s the following dedication:

all’amico Guglielmo Quarenghi

Guglielmo Quarenghi (1826—1882), four years Piatti’s junior, studied with his same teacher, Vincenzo Merighi (1795—1849) at the Conservatory in Milan. Quarenghi went on to become principal cellist at the Teatro alla Scala in Milan in 1850, and professor at the conservatory there one year after that. He composed mostly music for cello—caprices, transcriptions for cello and piano, some chamber music—, and also an opera. He is remembered today mainly for his Metodo di Violoncello (published in 1876).

Let’s now give a detailed look at the piece itself.

The Capriccio

The Capriccio sopra un tema della Niobe di Pacini, Op. 22, opens with a declamatory line in triple-stopped chords. These six bars move from D major through A major, E minor, then a diminished seventh of A major again, landing finally on a D major chord in second inversion announcing a cadenza. After the cellist has gotten the chance to warm his fingers with this virtuosic passage, it is time to hear the theme, which Piatti marks as TEMA. Moderato. The melody of “I tuoi frequenti palpiti” is clearly marked by the emphases, while the harmony is developed through the triplets runs, accompanied only by languishing left-hand pizzicatos. Piatti’s exposition and elaboration on the theme lasts for two whole pages, where the focus is set on finger independence to let the multiple voices come through. Several fermatas allow the cellist to make their lyrical qualities shine, directing the listener to the final cadence.

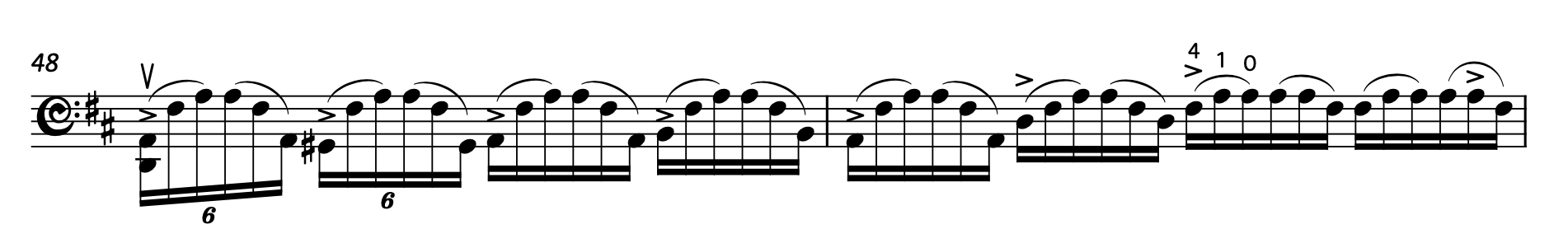

While Piatti neither marks what comes next as a “1st variation” nor adds a double barline to separate it from the previous part, it is clear that this is now something different. The next two and a half pages will hide the melody behind fast arpeggios on three strings, always clearly marking the notes to be emphasised.

Plenty of composers have written studies on this technique or inserted it in their concert pieces, and Piatti himself will compose his 7th Caprice, Op. 25 using exclusively arpeggios. The most uncomfortable part of this section is when the part climbs the 3rd and 2nd strings while keeping the open A string free to vibrate. Getting the bow nearer the bridge while reducing the weight is paramount.

A new, extended cadenza moment eases the pressure of the previous section and prepares the listener for what comes next: a sweetest Lento (slow) section. The key centre changes to D minor, with the line splitting into two voices: an upper, melodic, one, and a lower one in tremolo. This section, besides being of a stunning beauty, is very challenging since the fingers furiously tapping on the lower string run the risk of disturbing the upper melodic line. Pedagogically, this could be extracted to practice several finger dispositions in thumb position. This section is again quite lengthy, and contrasts the first part in D minor, with a second part that returns to D major, as if light had suddenly chased darkness away. A final, extended trill announces, like a trumpet blast, that something is approaching.

The next section, marked Allegro, is introduced by a short cadenza rich in chords and modulations. An arpeggio run on the Dominant of D major finally unveils the character that was hiding in the darkness: fast, furious, and jumping 16th-notes where the melody is accompanied by the constant drumming of the open A string. This is a Dominant pedal of sorts, akin to those we used to find in the ricercari, on whose form Bach Suites’ Preludes were based. This whole section is fiendishly difficult, all in double—and sometimes triple—stops, with several intervals of a tenth that could make it unplayable for smaller hands. Bow management is also terrifying, with the groups of four notes slurred by two and with staccato dots suggesting that all this should be played with a mix of spiccato and gettato. While practicing this, start slow, with a lot of relaxed weight on the string, and consider practicing the note changes in legato. Only when the left hand feels automatised, start accelerating but avoid voluntarily lifting the bow from the string, since this will make you lose control. The bow is innately elastic, as are the strings. With the right speed and weight, the bow will lift on its own, and you will be able to control the accentuations with precise, subtle movements of the wrist.

A short chord sequence introduces the final section, marked Più presto, obviously all in double and triple stops, that triumphantly brings to a close this magnificent and masterfully written Capriccio.

About this edition

This edition is mainly based on the oldest surviving printed edition, published by Ricordi in 1865 with plate number 36898, belonging to the “Tito” royal plant based in Milan and Naples. The manuscript of this piece, from which Piatti played in Pešt in 1843, is not to be found among all his other autographs in the Fondo Piatti-Lochis in Bergamo, nor anywhere else where library entries are documented. It can therefore be assumed to be lost. In the 1890s, a new printed edition was released by Leipzig-based publisher C. F. W. Siegel. Only one copy of this survives today, and it has been used for reference and fundamental additions. All relevant differences are listed in the Critical Notes at the end of this volume, alongside all musical mistakes and omissions found through careful analysis and instrumental practice of the piece. Concerning music notation, all elements in need of a refresh have been updated to current standards. Due to these edits, and even if the autograph will ever become accessible, this edition qualifies as a Critical Performance Edition. There is one more thing, though.

During the editing process, I contacted Maestro Antonio Meneses—since his recording was so crucial to helping me pinpoint some well-hidden mistakes—to inquire about whether he would have been interested in curating a version of this edition. To my delight, he enthusiastically accepted and, thanks to this new, outstanding collaboration, this edition now also contains—in addition to these notes, the original cello part, and the critical end-notes—a separated cello part edited by M° Meneses with his fingering, bowing, and performance suggestions.

This music deserves to be played and recorded much more than what it is now and, most of all, it needs to make its return on the note-stands of gifted students where it rightfully belongs.

My deepest thanks go to, in order of appearance, M° Fabrizio Capitanio of the Biblioteca Musicale “Gaetano Donizetti” in Bergamo for his patience and professionalism, to M° Alberto Jona of the Conservatorio “G. F. Ghedini” in Cuneo for his help in understanding Pacini’s opera production, and to M° Antonio Meneses for accepting to help me in creating this edition and for his invaluable contribution.

- The arias are:

– Preghiera, S’ è primo tuo vanto, for Bass (catalogue number 3012)

– Sogno d’Anfìone, Fra le notturne tenebre, for Bass (c.n. 3013)

– Cav., Il soave e bel contento, transposed for Soprano voice (the original is for Tenor) (c.n. 3015 & 3091)

– Cav., Invan tuoi preghi ostenti, for Soprano, and Duettino, Lagrime di piacere, for Soprano & Alto (c.n. 3017)

– Scena ed Aria, Tuoni a sinistra, for Soprano (c.n. 3034 & 3092)

– Coro e Passo de’ Ciclopi (c.n. 3090) ↩ - In cantatas and oratorios of the XVIII century, a cavatina was a simple and short aria performed at the end of a recitativo. In the melodramma, it was an aria without repeats, usually presented by the singer at its first entrance on scene, with the aim of portraying the character. When used in instrumental music, it would mean a piece of lyrical character without development. ↩

2 thoughts on “Piatti Opera Omnia – Episode 2”