Announcing Johann Simon Mayr’s Concerto n° 1 for Cembalo [Fortepiano] and Orchestra

What follows is an extract from M° Fabrizio Capitanio’s notes at the beginning of this edition. Find the full edition here and watch the promo video here.

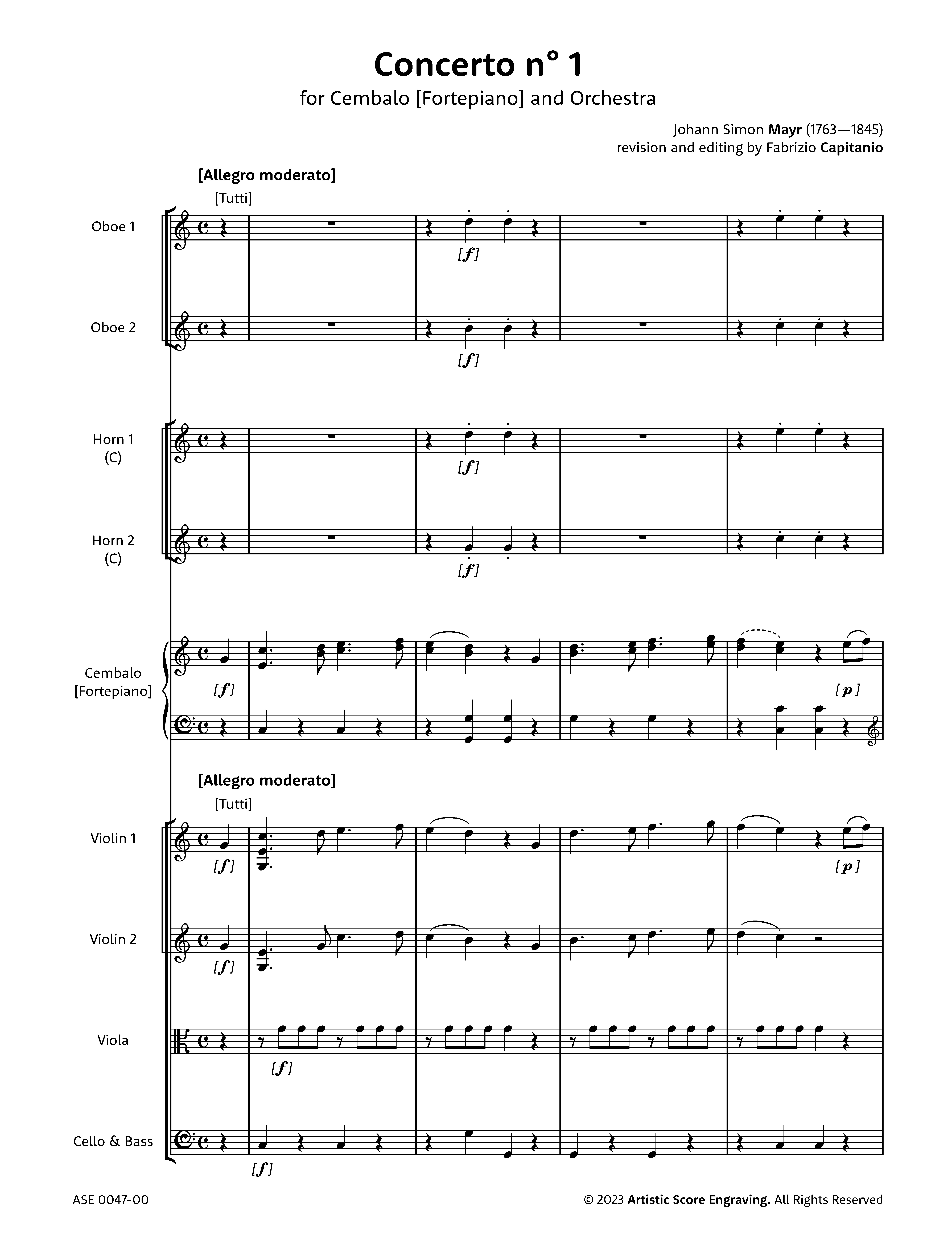

This is the first edition of a new series dedicated to the city of Bergamo, Italy. It takes its name from the popular dance from the Renaissance period of the same name, La Bergamasque! Here’s a sneak peek of the first page of the concerto:

I hope you enjoy this!

EDITORIAL NOTES

Historical preamble

In the extensive musical production of Johann Simon Mayr (Mendorf über Kelheim, Bavaria, June 14, 1763—Bergamo, December 2, 1845), author of many plays, oratories, cantatas, sacred music—works into which he poured most of his talent—the composition of instrumental music is to some extent ascribed to the occasion and, preponderantly, to pedagogy: the latter field was cultivated by the Bavarian musician with great interest and lasting passion.

The three concertos for harpsichord (or forte-piano) and orchestra—two in C major and one in F major—, kept in autograph score in Bergamo at the Biblioteca Musicale Gaetano Donizetti and at the Museo Donizettiano, were written by Mayr with obvious pedagogical purposes. It is natural to think that they were intended for some student of the Lezioni Caritatevoli di Musica, of which he was the founder and director. Characterised by a kind of piano writing that is technically not very complex, combined with a melodisation and harmonisation of a purely classicist style, one can glimpse in Mozart and especially in Haydn, the models kept by the composer during its elaboration, which took place in an era in which the style of the two great Austrian masters had long been phased out.

This concerto, like most of Mayr’s instrumental music, raises several questions about the date of composition: no document has been found that gives reliable indications in this regard. The only reference to his instrumental production, even if in a somewhat cryptic way, is derived from the Autobiographical Pages of Mayr himself:

Di poco numero sono le sue [riferito a sè stesso] composizioni stromentali, eccettuati alcuni divertimenti per Cembalo stampati a Venezia, ed altri a Londra, e cinque o sei concerti ed altrettante partite e notturni per stromenti da fiato.1, 2

In any case, an unpublished document that can provide some information about a possible date of composition ante quem can be identified in one of the concerto’s sources: it is precisely a transcription for solo harpsichord carried out by unknown hands, marked with the acronym I-BgmPf, kept at the Museo Donizettiano. This source is bound together with three other compositions, two of which are transcriptions for solo harpsichord from the original for orchestra (a ballet by Wenzel Robert Gallenberg and a symphony by Ignaz Pleyel) while the last one is an original composition for keyboard, titled «N° 6 Variazione [sic] Per Cembalo Piano Forte» by a not clearly identified «S.r Mastro [sic] W. Raffael».

The first of these three piano pieces provides us with a little help in establishing, if not the exact date, at least the period of composition of the concerto; it is Gallenberg’s Cesare in Egitto,3 a ballet written and performed in Naples in 1825. Since:

The music paper on which this ballet was copied is identical to that of the transcription of Mayr’s concerto (watermarks are also the same)

Both transcriptions appear to have been realised by the same hand because, even if a different pen was used, the handwritings are very similar.

It can reasonably be said that the ballet was transcribed at the same time or shortly after its staging

It is therefore inferred that the concerto was composed by Mayr in 1825 or 1826 at the latest. This would confirm what Mayr said in the aforementioned Pagine autobiografiche since, in the calculation of the ‘five or six concertos’, it is not possible to understand whether the number refers entirely to those for wind instruments (which is doubtful, at the current stage of studies) or also includes concertos for other instruments, such as the harpsichord.

As for possible performances, nothing is, of course, given to us about the if and when this concerto was performed with the author still alive: unfortunately, the programs of the numerous final performances of the students of the Lezioni Caritatevoli are almost completely untraceable today. Only the performances of the XX century are sufficiently documented.

The score and corresponding orchestral parts marked with the acronym I-BGi have been copied from the autograph in the first years of the XX century to celebrate a specific event. Kept at the Biblioteca Musicale “G. Donizetti” there is a series of unlisted concert programs relative to the commemoration in Bergamo of the centennial of Mayr’s appointment as Maestro di Cappella in the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore.4 The program of the concert organised for the evening of December 20, 1902, in the “concert hall of the Institute” (that is, the place that will become the Sala Piatti) textually reports the performance of the following piece: G. S. Mayr – Concerto in Do per pianoforte con accompagnamento di piccola orchestra, played by the teacher Prof. Alessandro Marinelli together with the orchestra of the students of the Pio Istituto Musicale.

Also interesting is the pencil annotation that appears on the inner cover of this copy-score:

“Eseguito in occasione della commemorazione centenaria della Morte di S. Mayr il giorno 16 giugno 1945”5.

On the «Giornale del Popolo» (then become Giornale di Bergamo) of Monday, June 18, 1945, there is a column titled “Il saggio finale del Conservatorio e la commemorazione di G. Simone Mayr”6 reserved to the piano, violin, and singing classes. More than forty years after the last performance, this concerto by Mayr was once more performed by an unidentified student of the piano class of M° Alfredo Rossi, accompanied by the small orchestra of the Istituto Musicale. The well-known donizettian biographer Guido Zavadini, at the time music history professor at the Istituto, was the main promoter of the initiative.

The last performance in Bergamo of this concerto happened during the celebrations for the 150th anniversary of Mayr’s death. On October 30, 1995, the pianist Luigi Di Ilio, accompanied by the Orchestra Stabile di Bergamo under the baton of Donato Renzetti, performed it at the Teatro Donizetti in the revision of the late M° Gianluigi Cerea.

Standards adopted in the Critical Edition

This critical edition has made use, albeit with necessary adjustments as appropriate, of the criteria established by the editorial committees relating to two of the most important initiatives for the philological recovery of Italian works from the first half of the nineteenth century:

- Edizione critica delle opere di Gioachino Rossini – Sezione prima: Opere teatrali, Pesaro, Fondazione Rossini / Milano, Ricordi;7 the editorial standards, elaborated from the Comitato della Fondazione comprised of Bruno Cagli, Philip Gossett and Alberto Zedda, have been published in the «Bollettino del Centro Rossiniano di Studi» anno XIV, n° 1, Pesaro, 1974, special issue dedicated to the criteria for the critical edition of all works by Gioachino Rossini.

An integration to these norms was published, once again on the «Bollettino del Centro Rossiniano di Studi» anno XXXII, Pesaro, 1992, inside an article redacted by Patricia B. Brauner titled “Opera omnia di Gioachino Rossini. Norme editoriali integrative per i curatori”;8 - Edizione critica delle opere di Gaetano Donizetti, Milano, Ricordi9, in collaboration with the Comune di Bergamo; the editorial criteria have been defined by a committee composed by Roger Parker and Gabriele Dotto (coordinating editors), Riccardo Allorto, Philip Gossett and Alberto Zedda.

General norms

The performance suggestions found in scores from the first half of the XIX century are, often, quite hasty; for example, a few dots traced here and there usually indicate a long section of “staccato” accompaniment. Dynamics are seldom shown in a coherent manner, and even phrasing articulations can vary between different proposals of the specified excerpt, sometimes even between instruments without clear musical reasons. Even Mayr, even if considerably more precise and scrupulous compared to many of his contemporaneous, cannot always escape the general rules of his time. Therefore, graphically signalling every intervention by the editor, or mentioning it in the apparatus, would bring an excessive and perhaps useless heaviness of the text. Besides, the reader’s attention would be diverted from really crucial interventions.

The following criteria have therefore been adopted:

- Performance suggestions found in one or more instrumental parts are clearly referred to other rhythmically or melodically identical parts; they have therefore been extended without graphical differentiations or mentions in the critical commentary. Particularly relevant situations have been mentioned in the apparatus, though;

- In certain cases, it has been deemed necessary to suggest playing techniques even when absent in the sources. Such indications are differentiated by dashed strokes (slurs, ties) or placed between square brackets (dynamics and articulations); when necessary, the editor’s choices have been mentioned in the critical commentary;

- When a clear error has been found in the sources for which a single logic solution exists, that has been corrected without graphical differentiations nor footnotes. If the solution presented itself in a non-univocal way, the choice, and reasoning behind it have been explained in a dedicated note;

- Given the general concordance between sources—after all, almost certainly they all derive from the autograph—it has been deemed appropriate not to adopt graphical differentiations that signalled the provenance of a certain solution from one source or from another one, to avoid needlessly cluttering the score with markings extraneous to the music. Only when, for a specific reason, this has been deemed interesting, the few differences to be found between the sources have been mentioned in the notes.

Graphical organisation of the score

The instruments order in the score follows modern practice; instrument names have been modernised as well.

When dyads are found in violas, the performance practice of the time prescribed for them to be played divisi, using separated stems in opposite directions. In this edition, the stems have always been unified.

The alternation between «Solo» and «Tutti», marked by Mayr on every instrument group (winds, cembalo, strings), has been kept in this edition only above the first visible stave of the system and, if necessary, above strings.

Graphical peculiarities found in the autograph, for example beam groupings and unbeamed notes, have been kept since they signify the different articulation that a phrase can assume.

Accidentals have been updated to modern practice; missing cautionary accidentals have been added in square brackets, while superfluous ones have been suppressed.

In cases when the autograph omitted a section of an instrument’s part, suggesting proceeding in unison with another instrument, the omitted section has been written out in full, using square brackets at its extremities to signal its insertion.

In the autograph, the stave generically labelled as «Basso» is to be assumed to be destined to “Cellos & Basses”, normally at the octave. At the time of Mayr, double basses were typically equipped with three strings, tuned in fourths (sounding pitch: A1, D2, G2, or G1, D2, G2). In case the lower limits of the instrument’s range were crossed, it was necessary to transpose a few notes at the higher octave, in unison with the cellos. With modern double-basses with four strings, this transposition is no longer necessary, and therefore this edition keeps the original notation. Striking cases of this procedure have been listed in a dedicated note.

The prescription «col basso», sometimes found in the viola part, has usually been interpreted as “at the octave with the bass” without additional mentioning in the notes in those cases where this is evident by logic and musical fullness. Dubious cases have, instead, been mentioned.

In other cases, instead, the viola part is completely missing, lacking both bar rests and the «col basso» suggestion. When, comparing analogous sections of the score or following musical logic, it was evident that violas had to play—either at the octave or in unison with the bass—this has been signalled in the notes.

Ornaments

When it was impossible to define with absolute certainty the rhythmical value of grace notes found in the autograph score, the original handwriting has been maintained. A slur between the grace note and the main one has been added only if already present in the original.

Regarding the notation of trills, Mayr adopts a peculiar notational system, regardless of the duration of the note: the long inverted mordent, or the simple inverted mordent.

This can bring confusion in case these signs are placed above quarter notes, like in bb 198 & 200 of the first movement: in fact, there is no way to understand whether the note has to be trilled or embellished with a simple mordent.

The mordent sign could represent the composer’s will to adopt resolution notes; this, though, is in contrast with bb 156-61 of the first movement and b 137 of the third movement, where the author has marked those notes explicitly. This notation marks only those also present in the autograph. It has been preferred to keep the original trill signs, then, leaving the last word to the performer.

Dynamics and Tempo markings

All dynamic and tempo markings have been uniformed to modern practice (example: ff for f.mo).

Missing nuances in instruments that enter at the same time or later have been added in square brackets, based on the previous or general dynamic. Only when absolutely certain, the square brackets have been omitted.

Articulation of the musical phrase

In every XIX century manuscript score there are overlooks, small inconsistencies, omissions, and contrasting articulation marks. With the goal of producing an editorial work as faithful as possible to the original, but at the same time clear and fully enjoyable without ambiguity by the modern performer, the following rules have been followed:

Minimal and unimportant differences in articulations and slurs, where the composer’s will appeared crystal clear, have been uniformed without recurring to comments or graphical differentiations;

When sources show a recurring phrase without repeating the same articulation, this has been extended to all identical repetitions without mentioning it in the notes. As stated above, dashed slurs have been used where phrasing suggestions were not born out by models found in the sources;

The different notations for the staccato—dot or vertical bar—found in the autograph have been kept.

Bottom Line

The Critical Notes for this Concerto can be found in the full edition available here. You can hear how the Concerto sounds at this YouTube link.

Join my mailing list to keep up to date with the latest news and to get free excerpts of every published edition.

Thank you for your time and continuous support.

Michele Galvagno

- Few are his [referred to himself] instrumental compositions, if we exclude a few divertimentos for Cembalo printed in Venice, and others in London, and five or six concertos and as many partitas and nocturnes for wind instruments. ↩

- The Pagine autobiografiche date back to 1827 and are kept in autograph manuscript form at the Biblioteca Musicale Gaetano Donizetti (I-BGi, Dono Massinelli-Mandelli, PREIS.472.6423). They have been published in Giovanni Simone Mayr, Zibaldone preceduto dalle Pagine Autobiografiche, curated by Arrigo Gazzaniga, Bergamo, Grafica Gutenberg Editrice, 1977; the quoted excerpt can be found at p 18. In a note, Gazzaniga adds to the autograph list also a Symphony and two Divertissements for orchestra, three Concertos for piano and orchestra, a Trio concertante for three violins and orchestra, besides several pieces for solo instrument (piano, violin, flute, organ, harp). ↩

- Gallenberg, Wenzel Robert, count of (Vienna, 1783—Rome, 1839). Of ancient and noble family, he studied in Vienna with Albrechtsberger. Settled in Naples, he was active above all as a composer of ballets and occasional pieces. ↩

- MÎA – Pio Istituto Musicale Gaetano Donizetti in Bergamo | Commemorazione di Giovanni Simone Mayr 1802-1902 | Centenario della nomina di Mayr a Maestro di Cappella della Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore – Programma, Officine dell’Istituto Italiano d’Arti Grafiche, [Bergamo, 1902]. ↩

- Performed in occasion of the commemoration of the 100th year since the Death of S. Mayr on June 16, 1945. ↩

- Final exhibition of the Conservatory and commemoration of J. S. Mayr. ↩

- Critical edition of Gioachino Rossini’s works – First section: Operas. ↩

- Gioachino Rossini Opera Omnia. Additional editorial norms for curators. ↩

- Critical edition of Gaetano Donizetti’s works. ↩