Phonetic transformations (Part 1)

Under specific conditions in the Serbian language, words undergo subtle changes to certain consonants and vowels based on surrounding letters and sounds. These changes are called Phonetic transformations, or, in Serbian, Гласовне промене—literally, “voice changes”. Given that the Serbian language has a phonetic spelling, all transformations that occur when speaking are also made in writing, provided that the word retains its meaning and must be easy to pronounce. Should a word lose its meaning due to a transformation, then an exception arises, and the transformation does not occur.

There are several kinds of transformations, grouped by whether consonants or vowels are being changed. Transformations involving vowels are:

- The “mobile A”

- The transformation of the Л in О

- The assimilation

- The dissimilation of Е and О

- Other mobile vowels

Transformations involving consonants, instead, are:

- The assimilation based on the sonority

- The assimilation based on the place of articulation

- The first and second palatalisations (the second is called сибиларизација in Serbian, that could be translated as something similar to “wheeze-ation”, or “hiss-ation”).

- The iodisation

- The dissimilation

We will start today by looking at the assimilation of consonants based on their sonority.

Assimilation based on the sonority

This first transformation is called Једначење сугласника по звучности, which literally means the “equation of consonants based on the sonority” (IT: assimilazione in base alla sonorità).

It occurs when two consonants of different sonority (EN: voiced / unvoiced; IT: sonore / sorde; СР: звучни / безвучни) are found next to each other in the same word. To make the word easier to pronounce, the sonority of the first consonant is assimilated to that of the second one. So: a voiced consonant followed by an unvoiced one is changed to its unvoiced equivalent, while an unvoiced consonant followed by a voiced one is changed to its voiced equivalent (if present).

Most voiced consonants in Serbian have an unvoiced corresponding one:

| Voiced | Unvoiced |

|---|---|

| Б | П |

| Г | К |

| Д | Т |

| Ђ | Ћ |

| Ж | Ш |

| З | С |

| Џ | Ч |

| — | Ф |

| — | Х |

| — | Ц |

Keep this table handy when looking at the following examples.

Unvoiced becomes voiced

п > б

When visiting Belgrade, you need to see the fortress of Калемегдан, atop which there are still many cannons on display. Топ (EN: gun, IT: cannone), then, becomes Тобџија (EN: gunman, IT: cannoniere). When learning this, try to go through all passages: топ would become топџија, but п is unvoiced and comes before ђ which is voiced. П must, therefore, change to its unvoiced equivalent б. Thus, we have тобџија.

т > д

Сват means someone invited to a wedding party, while свадба represents the wedding party itself.

Сват > сватба > свадба

к > г

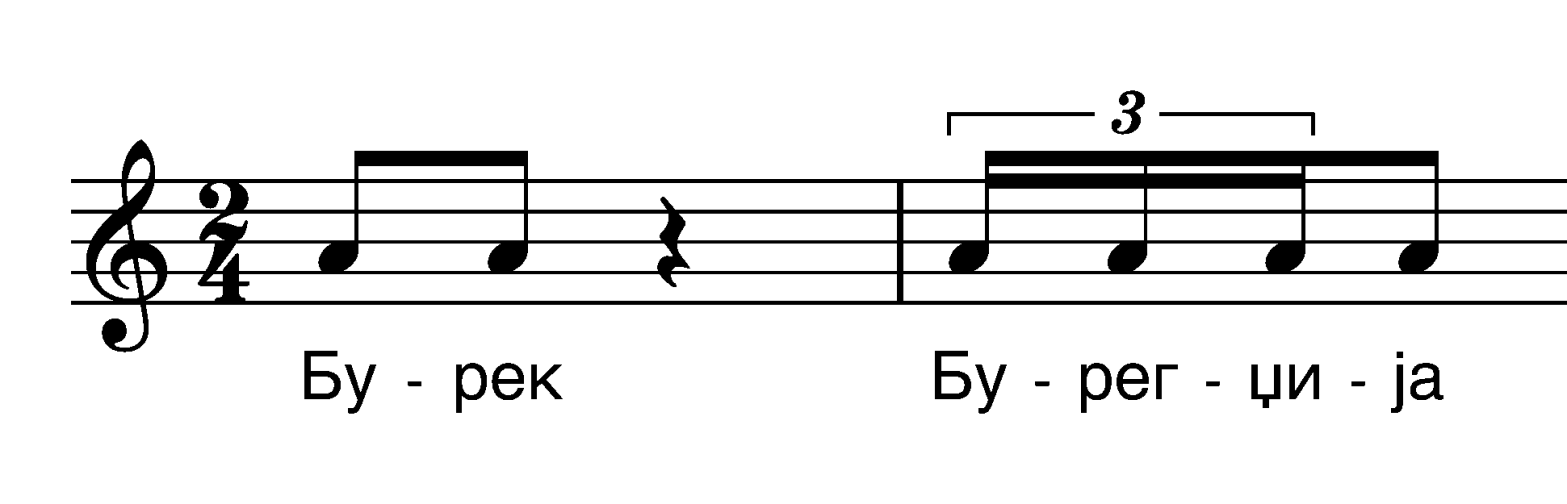

Something typical that you need to try when you are in Serbia is бурек, a kind of pastry made of a thin flaky dough such as filo with a variety of fillings, such as meat, cheese, or even sweet. Between 7 and 8 AM, you can see long queues in front of bakeries where people try to get their hands on бурек before it’s over. If the sales assistant is brilliant, they will shout:

Ко не чека бурек?

That is, “Who’s not in line for бурек?”, allowing people who just came for some bread or anything else but бурек to avoid waiting a considerable amount of time.

Specialised places that produce бурек are called бурегџиje (singular: бурегџија).

Бурек > бурекџија > бурегџија

ч > џ

When you want to order something at the restaurant, you use the verb поручити (EN: to order, IT: ordinare). The order itself, that is what you’ve asked for, is поруџбина. On menus, you will often find a section called јело по поруџбини, that is the equivalent of the French “à la carte”, that is, when you choose from the list.

Поручити > поручбина > поруџбина.

с > з

This example is a bit more complex, as it contains two transformations. Гост means guest (IT: ospite), but the word for party is гозба. The transformation path is as follows: гост > гостба > (the т falls for dissimilation) госба > гозба1.

Voiced becomes unvoiced

This can happen under several circumstances: the moveable A, called непостојано А, both in the genitive singular and in the nominative singular of certain substantives and adjectives, brings a voiced and an unvoiced consonant close together, causing the assimilation. Moreover, some prefixes and suffixes can cause this.

б > п

The animal symbol of Belgrade is the sparrow (IT: passero, SR: врабац2. The suffix for the genitive singular is –A, which would make it врабац-а. This process causes the penultimate A to fall away, resulting in врабца. Б and Ц, though, can’t stay close together, so the Б becomes П, resulting in врапца. Another, similar example is пољубац (IT: bacio, EN: kiss), which becomes пољупца.

The adjective љубак (IT: carino, EN: cute) is in masculine form, but it would change its ending for the feminine and neuter genre, becoming љубака and љубако. This would cause the A to fall, bringing б and к in touch. Б then becomes п and we get љупка and љупко.

Finally, when we would like to mention that something belongs to something else, we add the suffix –ски to the end of the word. For example: клуб (EN/IT: club) would become клубски but, by now you know the drill, б becomes п and we get клупски (EN: of the club, IT: del club).

з > с

Following the same rules listed in the previous section, we now simply go through a few examples.

Долазак (EN: the arrival, IT: l’arrivo) would make the following steps: долазака > долазка > доласка

Узак (EN: narrow, IT: stretto) > узака/o > узка/o > уска/o

Париз+ски (to mean Parisian, IT: parigino), would make an extra step: Парисски > Париски (the doubled с would fall because of the dissimilation rule we will cover in a future episode).

д > т

Сладак (EN: sweet, IT: dolce) > сладака/о > сладка/о > слатка/о

The verb ценити (EN: estimate/assess, IT: valutare), would change when prefixed with под (EN: under, IT: sotto). Под-ценити > потценити.

ж > ш

Тежак (EN: hard/complex, IT: difficile) > тежака/о > тежка/о > тешка/о

The verb “to hold” (IT: tenere) is држати in Serbian. Some substantives derive directly from verbs by replacing the verb’s ending with the suffix –ка. The –ти of the infinitive is replaced by –ка, becoming држака. The ‘A’ falls, leaving држка, with the ж becoming ш, thus дршка.

ђ > ћ

Rust (IT: ruggine) is рђа in Serbian. If we would like to mention that something has a “rusty colour”, then we need to add the suffix каст to the end of the word. The A will fall again, leading to the following transformation: рђа > рђакаст > рђкаст > рћкаст.

г > к

The word “other” (IT: altro) is други in Serbian. The word “different” (IT: diverso) uses the same root and adds a somewhat complex suffix: –чији. The word is thus composed and the transformation from г to к happens, with the final и falling away: други > другчији > друкчији.

Exceptions and peculiarities

The consonants ф, х, and ц have no voiced correspondence, making them remain unvoiced when they come in the first place. They still cause the transformation in other consonants if they are found in the second place.

The sonants (в, р, л, љ, ј, м, н, њ) are always voiced and do not transform in front of unvoiced consonants. For example: цинк (IT: zinco, EN: zinc) or вампир (IT: vampiro, EN: vampire). At the same time, unvoiced consonants in front of sonants do not become voiced: шетња (IT: passeggiata, EN: stroll (walk)), усне (IT: labbra, EN: lips).

Finally, a few exceptions:

- The letter Д doesn’t change in front of С and Ш, nor when it is found at the end of a prefix (од-, град-, људ-, пред-, под, …)

- The letter ђ doesn’t transform in front of the suffix –ство, for example вођство (IT: guida, EN: guide).

- Most names of foreign origin are not transforming, for example: предсетник (IT: presidente, EN: president). It should be претседник, and, indeed, it is one of the few pronunciation exceptions to the Serbian language, with the д being pronounced т, but it stays written with the д.

Bottom Line

That’s it for today, and I hope you enjoyed it. In the next lesson, we will tackle the assimilation of consonants based on the place of articulation, another quite hefty topic! Stay tuned!

If you like what I do, feel free to share this article with your peers.

I also have a mailing list, dedicated mostly to my activity as a music engraver and sheet music publisher. You’re more than welcome to join!

I suggest you also give a look at the rest of my website, to see о чиме се бавим! 😉

See you soon for another lesson!

3 thoughts on “An Italian cellist’s journey into Serbian Language — Lesson 10”