Phonetic transformations (Part 3)

Welcome back!

I hope you are enjoying these lessons that mix the study of the Serbian language with my musical and engraving skills.

Get ready because today we delve deep into yet another transformation, which promises to confuse the cards on the table even more! Let’s get started!

First palatalisation

While the two transformations we looked at in the previous lessons (10, 11) happened when two consonants came into contact, the first palatalisation occurs when specific consonants find themselves in front of specific vowels. The two main manifestations of this phenomenon are:

- When the velar consonants к, г, and х are followed by the vowels е or и, they respectively become ч, ж, and ш.

- When the dental consonants ц and з transform into ч and ж in specific circumstances.

To summarise:

| Original consonant | Transformed consonant |

|---|---|

| К, Ц | Ч |

| Г, З | Ж |

| Х | Ш |

This transformation is, according to lore, a fairly recent addition to the Serbian language and, thus, one can find two variations of certain words, one palatalised and one not.

Let’s now look at some practical examples.

К, Г, Х + е

Vocative singular

The vocative singular of masculine nouns usually ends in -e,1 so when the root of the word ends in к, г, or х, we witness this transformation.

The word друг (IT: amico; EN: friend), transiently becomes друге, but the г in front of the -e becomes ж, thus resulting in друже.

Дух (IT: spirito; EN: spirit/soul) temporarily becomes духе before assuming its final state as душе.

Mentioning a hero (IT: eroe) calls for the Serbian word јунак. To call him, you would need the vocative case, which should result in јунаке. The palatalisation, though, causes the к to become ч, resulting in јуначе.

Verbs in -ић

Some verbs whose infinitive ends in -ић, have the root of the present tense ending in either of our three friends: к, г, х. Тhe termination of the first-person singular of the present tense of these verbs is -ем, while, for the third-person plural, it is -у.

The verb вући (IT: tirare; EN: pull), found, for example, printed on doors to show you the opening direction, has вук- as the root of the present tense. The first-person singular would then be вукем, if it weren’t for the palatalisation that shapes it into вучем. In the 3rd person plural, though, the root -к makes a comeback as вуку.

Сечем means “I cut” (IT: io taglio), as in сечем хлеб (IT: sto tagliando il pane; EN: I’m slicing the bread). Its infinitive is сећи, while its root is сек-. The palatalisation makes the -к become -ч.

A final example—important because it bears an exception—is стићи (IT: arrivare; EN: to come/arrive), whose root is стиг-. Тhe -г becomes -ж, resulting in стижем. The exception is that, also in the 3rd person plural, the -ж remains: стижу (IT: arrivano; EN: they come).

Actually, there is more to this. There is a special verbal tense in Serbian called aorist, which is some kind of hopelessly gone past. Seriously, though, this tense indicates pure and simple action, regardless of time and duration. We will get back to it in due course, but for now, let’s say that verbs whose present root ends in к, г, х are subjected to the first palatalisation in the II & III person singular. A single example will suffice: пећи (IT: arrostire; EN: to roast), has пек as root. The aorist ending for the II/III person singular is -е, so we get пеке, which palatalises into пече, for the same rules stated above.

Ц, З + е

Аgain in the vocative case, nouns (and derived adjectives) whose root ends in ц and з, undergo the palatalisation process. For nouns ending in -ац, three steps occur:

- The final -ц is palatalised

- The “moveable A” falls, possibly bringing two consonants in touch, which then…

- …may undergo further transformations.

Let’s look at a few examples. The word “prince” (IT: principe) is кнез in Serbian. The vocative adds -e to the end, resulting in кнезе. This causes the palatalisation of the з into ж, giving us кнеже (or its possessive adjective кнежев).

Ramping up with the difficulty, the word отац means father (IT: padre). First we add the -e (отаце), then the -a falls (отце), followed by the palatalisation of the ц into ч (отче), and concluded by the dissimilation of consonants that causes the first of two consonants to fall out (оче, or its possessive adjective очев). These are among those things one needs to learn by heart.

Another example with the ц is ловац (IT: cacciatore; EN: hunter). From ловаце we can either let the A fall first and the palatalisation occur later or viceversa, the result is the same: лов(а)це > ловче/ловчев.

Жабац, the Serbian word for “frog” (IT: rospo/rana) is more interesting. Adding -e gives жабаце, which causes the fall of the A and the palatalisation: жаб(а)це > жабче. Here we go back to the first lesson, where two consonants of different sonorities must learn to agree. Б being voiced and ч being unvoiced forces the first one to change into п, giving us the final result of жапче/жапчев.

К, Г, Х, Ц, З + derivation suffixes

When a word’s root ends in either к, г, х, ц, or з, it walks down the palatalisation path when it comes in contact with derivation suffixes such as -ић, -ица, -ина, -ерда, -ба, -ан, -ски, … Let’s try to go with order.

Ић and ица are both diminutive suffixes. The word круг (IT: cerchio; EN: circle) would become кругић, were it not for the palatalisation changing the г into ж to give кружић (IT: cerchietto; EN: hairband). Девоијка (IT: ragazza; EN: girl) would become девојкица, but the transformation changes the к into ч, resulting in девојчица (IT: ragazzina; EN: little girl).

The suffixes -ина and -ерда, can be augmentative endings (IT: suffissi accrescitivi), though they also like to subtly change the meaning of the word they modify. A hero (IT: eroe) is јунак in Serbian.

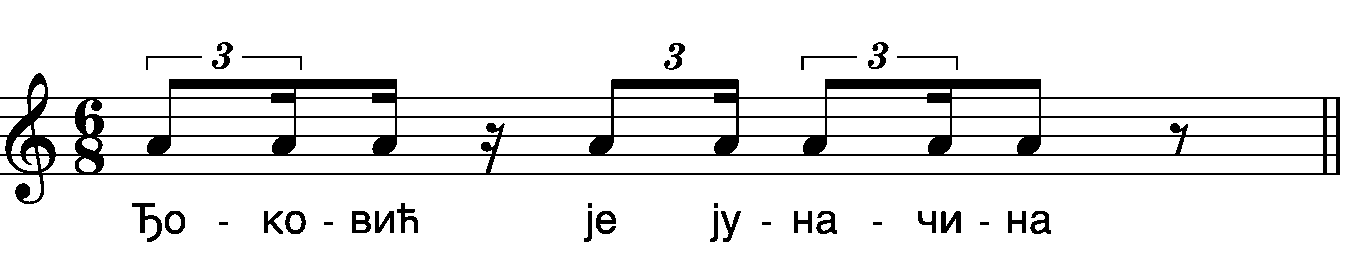

Јуначина (passing from the јунакина before the palatalisation) means “great hero”, for example:

Ђоковић је јуначина!

An interesting example is the word прах (IT: polvere; EN: dust). In its base form, it actually indicates the powdery state of a substance. For example, powdered sugar (IT: zucchero a velo) is шећер у праху (literally “sugar in powder”). If we want to talk about dust itself, the annoying thing accumulating absolutely everywhere before you’ve even finished cleaning it for the first time, is called прашина in Serbian. To get there, one adds the suffix -ина to прах (прахина), with the х becoming a ш during the palatalisation process.

The suffix -ин, instead, is usually denoting a possessive adjective. Thus, when we say the word куварица (IT: cuoca; EN: cook (f.)), to get to the possessive adjective we would need to remove the -а ending and add the -ин suffix. That would bring us to куварицин, but the ц needs to change in front of the и, becoming куваричин (it: della cuoca; EN: the cook’s).

This does not happen if the adjective is derived from a proper noun (e.g., Бранка remains Бранкин, but Милица chances into Миличин)

Adding -ан to a noun creates a qualifier based on it. For example: смех means laughter (IT: riso), while something ridiculous (IT: ridicolo) is смешан. How did we get there? Смех+ан gives смехан, with the х being transformed into a ш by the palatalisation.

The word радник (IT: operaio; EN: worker) needs the suffix -ски to become an adjective. There are a few more passages here, though: from радникски, the к becomes ч following the palatalisation, and the ч causes the falling of the с through the dissimilation (раднички). So, it seems that in the dissimilation it is not said that the first consonant will be the one to fall. Once we get to that transformation, things will hopefully get clearer.

The final example of this long section shows how the word “father” (IT: padre), отац in Serbian, can become homeland (IT: patria) through the addition of the suffix -бина. Starting from отацбина, we have the first palatalisation, causing the transformation of the ц into a ч. Then, we have the assimilation based on sonority that prevents two consonants of the same sonority from living peacefully next to each other. The unvoiced ч must conform to the voiced б that follows, becoming џ, thus resulting in отаџбина.

К, Г, Х + и (а)

Body parts

There are only two examples of this transformation, both referring to parts of our body: око (IT: occhio; EN: eye) and ухо (IT: orecchio; EN: ear), when said in the plural form, respectively become очи and уши. The palatalisation process has shaped the к into ч, and the х into ш.

Verbs derived from nouns

Some verbs, instead, derive from nouns. Removing the noun’s ending and adding the verb’s one, can make either of к, г, or х come in touch with the vowel и, requiring palatalisation. So, the word лек (IT: medicina; EN: medication), when adding the verbal suffix -ити, cannot stay as лекити, but needs to be changed into лечити (IT: curare; EN: to heal).

The word грех (IT: peccato; EN: sin), instead, needs the palatalisation to go from грехити to грешити (IT: peccare; EN: to sin.).

К, Г, Х + љив/ив

Adjective derived from verbs ending in -ати/-ити whose root terminates in к, г, х, are subjected to the palatalisation of this last character. Thus, лагати (IT: mentire; EN: to lie) adds -љив to its root лаг- (лагљив), but the г cannot stay like that and must palatalise, becoming ж. The final result, therefore, is лажљив (IT: bugiardo; EN: liar). It is interesting to notice that also the present tense of these verbs undergoes the same transformation: to say “I lie” (IT: io mento), one says ја лажем.

Exceptions

There are few cases where the palatalisation does not occur.

The suffix -ин

When the consonants к, г, х are alone in a bisyllabic word, the palatalisation risks altering its meaning. Thus, бака (IT: nonna; EN: grandma) stays as бакин, (IT: della nonna; EN: grandma’s) not бачин.

The suffix -ица

If the syllable preceding the suffix contains ч or ћ, the palatalisation is not needed: девојчица (IT: ragazza; EN: girl) > девојчицин (IT: della ragazza; EN: the girl’s), not девојчичин.

When forming diminutives, the following are not palatalised:

- Kinship nouns: декица (IT: nonnino; EN: grandaddy), …

- К, г, х are preceded by another consonant: патка > паткица (IT: papera/paperina; EN: duck/little duck), …

Accusative plural of masculine nouns

The accusative plural of masculine nouns normally ends in -е. As we saw at the beginning of this lesson, also the vocative singular ends in -e, but in that case, the palatalisation occurs. Here, instead, it does not: лешник > лешнике (IT: nocciola; EN: hazelnut).

Bottom line

That’s it for today, and I hope you enjoyed it. In the next lesson, we will tackle the second palatalisation, which will hopefully look less daunting after what we faced today! Stay tuned!

If you like what I do, feel free to share this article with your peers.

I also have a mailing list, dedicated mostly to my activity as a music engraver and sheet music publisher. You’re more than welcome to join!

I suggest you also give a look at the rest of my website, to see о чиме се бавим! 😉

See you soon for another lesson!

- Also the accusative plural of masculine nouns ends in -e, but there it doesn’t cause palatalisation. ↩

I love it!

LikeLike