Phonetic transformations (Part 4)

Welcome back!

Today, we are going to look at yet another phonetic transformation, very similar to the one we saw last time. Let’s get started with the second palatalisation!

Second palatalisation

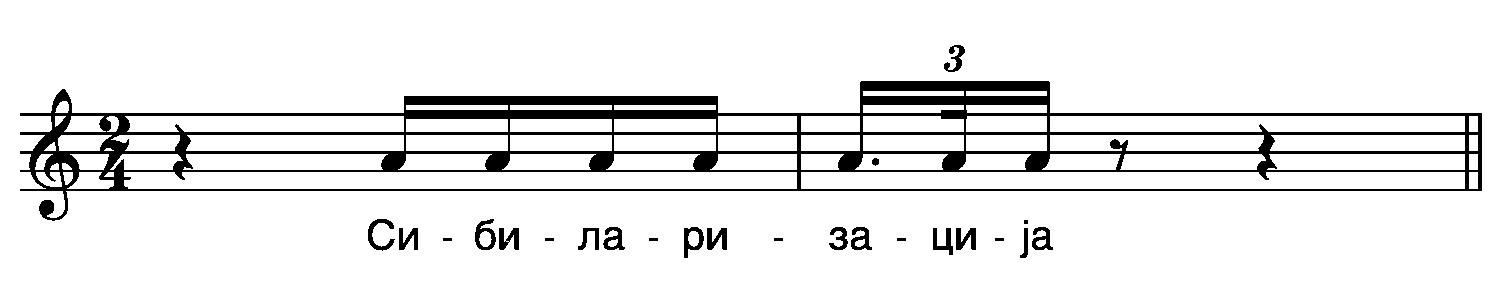

This transformation was called “second palatalisation” in the book I was studying from, but in Serbian, it is actually called сибиларизација (IT: sibilarizzazione; EN: sibilarisation — none of these words natively exist in Italian, or in English, which may have caused the different naming).

It occurs when the consonants к, г, х come in contact with the vowel и and get transformed into ц, з, с. The potential for confusion with the first palatalisation here is great because the original consonants are the same, and some destination consonants here were parts of the starting consonants there. Here’s a table that tries to clarify:

| Original consonant | Transformed consonant |

|---|---|

| К | Ц |

| Г | З |

| Х | С |

I suggest going back to the previous lesson to compare the two tables. It may help to create a mind map so that you know that, for example, the two original consonants of the first palatalisation (к, ц > ч and г, з > ж) are now origin and destination in the second palatalisation (к > ц and г > з). For the х becoming с it is harder to find a logical link, and it will hopefully become clearer in the examples.

Feminine nouns in -ка, -га, -ха

Feminine nouns ending in -ка, -га, -ха transform the last consonant in the dative and locative singular case, whose ending is -и. For example, рука (IT: braccio; EN: arm), would be руки in those cases, but the к becomes a ц, resulting in руци.

Another body part, нога (IT: gamba; EN: leg), would become ноги and, instead, becomes нози.

Similarly, књига (IT: libro; EN: book) becomes књизи and not књиги, and банка (IT: banca; EN: bank) becomes банци and not банки. Nouns with х are rarer: снаха (IT: nuora; EN: daughter-in-law) becomes снаси and not снахи.

So far, this transformation seems to have stemmed from a need for an easier pronunciation.

Masculine nouns

Every case of the masculine plural apart from the genitive and accusative have the potential of bringing к, г, х in contact with the и because their endings are, respectively, -и for the nominative and vocative cases, and -има for the dative, instrumental, and locative cases.

The word ђак (IT: alunno; EN: student), would become ђаки/ђакима, but the к becomes ц and thus the correct form is ђаци/ђацима.

Moving on to fruits, орах (IT: noce; EN: walnut) becomes ораси/орасима instead of орахи/орахима.

If one day you feel like a pancake with walnuts, something every good kiosk or restaurant in Serbia should have, say this:

Хоћу једну палачинку с орасима!

Looking at animals, we have the word паук (IT: ragno; EN: spider), which becomes пауци/пауцима, and noт пауки/паукима. More seriously, грех (IT: peccato; EN: sin), becomes греси/гресима.

Finally, предлог (IT: proposta; EN: proposal) becomes предлози/предлозима.

Imperative of verbs in -ћи

If the present tense’s stem ends in -к, г, х, then it will clash with the imperative endings of -и, -имо, -ите, thus requiring palatalisation. The three endings correspond to the 2nd person singular and to the 1st & 2nd person plural.

The verb пећи (IT: arrostire; EN: to roast sth) has пек- has the present stem (do you recall the example we had for the first palatalisation?), and becomes пеци/пецимо/пеците instead of пеки/имо/ите.

Similarly, the verb рећи (IT: dire; EN: to say), will have its imperative form as реци/рецимо/реците.

Imperfect tense of verb in -ћи

I have seldom seen this tense be used in my everyday experience in Serbia, possibly because this is not a tense much apt to conversational subjects1. It shows the same issue as the imperative for verbs whose present stem ends in -к, г, х, because the endings of the imperfect tense are, respectively: -ијах, -ијаше, -ијаше; -ијасмо, -ијаше, -ијаху.

Let’s use the same example of before with the verb пећи: the contact of the present stem with the vowel и will trigger the palatalisation. The result, thus, will not be пекијах, rather пецијах.

Perfective and imperfective verbs

Perfective verbs are used when one action is final and executed only once, while imperfective verbs are dedicated to repetitive actions or actions that are currently being performed. This is a quite complex topic over which we will come back again in the future, as giving examples now would not be of much help for your understanding of the second palatalisation.

Exceptions

The second palatalisation does not occur in the dative and locative singular cases under specific circumstances. For example, proper nouns do not get changes: saying “to Olga” will therefore be Олги, not Олзи! Same story for toponyms such as Волга > Волги (EN: on the Volga river; IT: sul fiume Volga), and not Волзи. There are some of them, though, which do require the palatalisation: Африка becomes Африци and not Африки.

Words of only two syllables, such as бака (IT: nonna; EN: grandma) keep their form to avoid altering their meaning. “To grandma” will thus be баки and not баци.

Feminine nouns that denote a feminine job occupation do not palatalise: библиотекарка (IT: bibliotecaria; EN: librarian (F)) becomes библиотекарки.

Family nouns such as унука (IT: nipote; EN: nephew) and супруга (IT: coniuge; EN: sposa) can have both forms, and they are both considered correct.

Nouns ending in -ка that denote a nationality also do not change: италијанка (IT: italiana; EN: Italian (F)) keeps the к in the dative/locative as италијанки.

Nouns with specific consonant groups (зг, цк, ск, чк, ћк, тк, рк) keep the form, for example:

- коцка (IT: dado; EN: die) becomes коцки

- мачка (IT: gatto; EN: cat) becomes мачки

- патка (IT: papera; EN: duck) becomes патки

Finally, words of foreign origin ending in -га do not palatalise: колега (IT: collega; EN: colleague) becomes колеги and куга (IT: peste; EN: plague) becomes куги.

Bottom line

That’s it for today, and I hope you enjoyed it. In the next lesson, we will take a small break to cover a quite funny subject! Stay tuned!

If you like what I do, feel free to share this article with your peers.

I also have a mailing list, dedicated mostly to my activity as a music engraver and sheet music publisher. You’re more than welcome to join!

I suggest you also give a look at the rest of my website, to see о чиме се бавим! 😉

See you soon for another lesson.

- Upon further inspection, the Serbian imperfect is similar in role to the Italian’s passato remoto, and to the past simple in English. ↩

One thought on “An Italian cellist’s journey into Serbian Language — Lesson 13”