The Music of the Opera Zarqa Al-Yamama

Welcome back!

Last time, we analysed in depth how the story became a libretto and how the libretto became an opera. We encountered the characters of the story and went through the synopsis of the whole opera.

Today, we will analyse its music, going scene by scene to describe what you hear and how this may be connected to the drama unfolding on the stage.

Brace up, we’re going to start!

ACT 1

Scene 1

First things first: there is no ouverture! This is certainly a defining feature, though not unheard of in contemporary opera. In the past, having an ouverture was needed to present the musical themes so that the listeners would feel more engaged. Times change, though, and one needs to adapt.

The pizzicato of the double basses open the dances, in a 5/4 metre, with Arabic Percussion (both off- and on-stage) and Alto Flute soon joining the fray. Afira starts singing her opening aria, and the opening interval is that of a tense major seventh, immediately setting the mood of the piece.

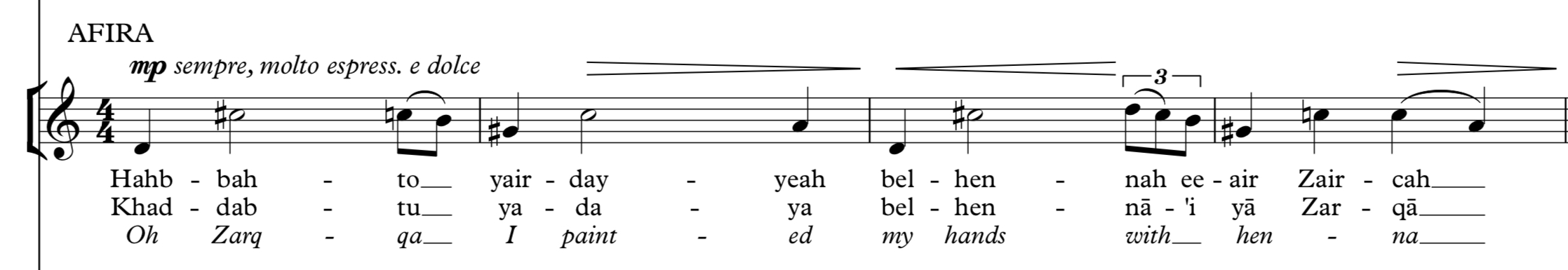

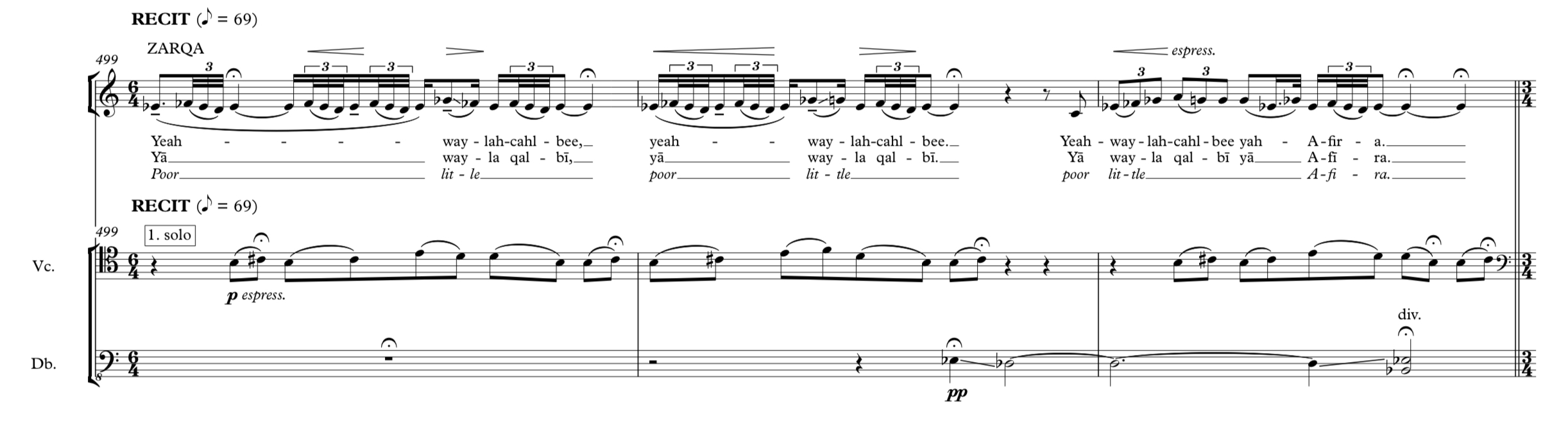

While this is sung by Afira, this is—in reality—Zarqa’s theme, which will return several times in the course of the opera. Every time Zarqa makes a prophecy or its effects are about to unfold on stage, we can hear this melody coming back, more or less variated. The orchestral intermissions between the vocal regions provide us with access to a signature feature of Lee Bradshaw’s music, which I would call “enriched ornaments”. They are irregular groups of notes (tuplets) found at the beginning or at the end of a bar which greatly help propel the musical discourse forward. Here’s an example in the woodwinds:

Zarqa’s entrance brings in an entirely different mood: her line is an almost chromatic recitative, dwindling between F and A, a major third above, while keeping F-sharp as a balancing focus. Accompanying her are the strings alone, playing in their highest possible register, a stark contrast with the message Zarqa is conveying, that “love shall guide your way”.

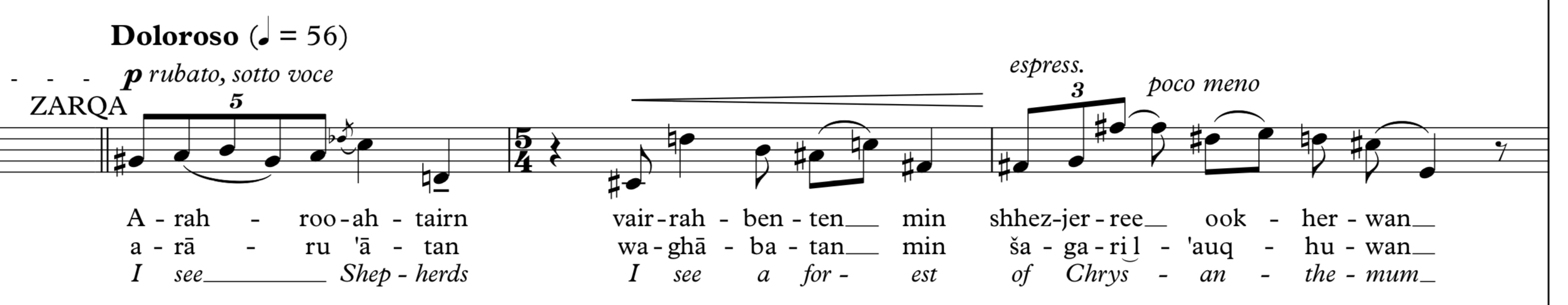

Afira then resumes singing her melody, asking Zarqa what she sees beyond the horizon. Zarqa’s answer, marked “Doloroso” (painful) in the score, finally takes back the major 7th interval that was hers, with even a minor 9th jump marking the words “I see”.

When Zarqa reveals she is seeing heartbreak in their future, the melody starts switching between major and minor 7ths, conveying the uncertainty. The low strings and woodwinds introduce a line that will also return again and again in precise spots, symbolising the desert storm:

Whenever we hear it, it represents the wind over the desert, or the storm in the distance. Furthermore, it tells us that something is about to change.

The first scene ends with the off-stage choir singing an Orthodox-style chant in the distance, to which Zarqa replies with a final “I see heartbreak” on a D to C-sharp major 7th.

Scene 2

The second scene abruptly begins with the brasses blowing the “theme of tyranny” of King Amliq, who is now being pushed forward on stage atop his obsidian throne.

Mr. Bradshaw has already explained his view on this theme and its intervals in his interview here on the blog.

The horns quickly follow with a solo line whose intervals will be made their own by both Amliq and his attendant, Riyah.

Don’t allow the apparent innocence of the perfect fifth (symbol of royal power) fool you; look instead at the final contour: E to E-flat/D (transposed from the horn part), another 7th! The Snare Drum line aggressively depicts the military power of the king with which he subdues his subjects.

A recitative by Riyah follows, in which he presents Hazila and Qabis to the king, coming to ask for justice concerning their custody dispute. The thundering voice of the king alternates big interval jumps with chromatic descents, a possible expression of his intolerance through which he still needs to express a sensible judgment.

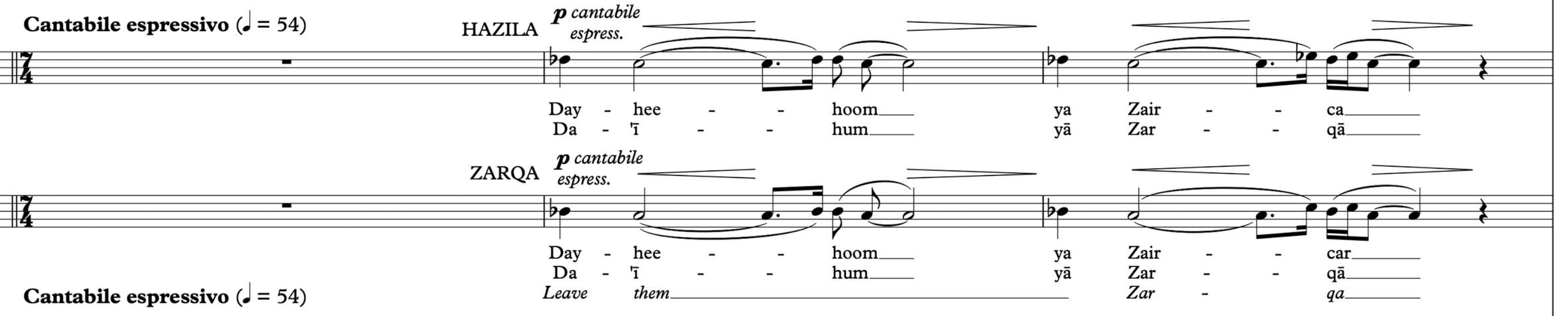

What follows is one of the most beautiful melodic moments of the entire opera, labelled “Lullaby”, in which Hazila prays to the king for justice (“Our sons are our hope and security”).

This is accompanied by solo woodwinds and the third horn, the harp and the strings playing tremolo and pianissimo. The aria, in ABA form, continues with a “Fanfare of the Dead”, slightly faster, with only the lowest representatives of each instrument family making the cut in the orchestration this time. The lullaby then comes back with an ornamented closing.

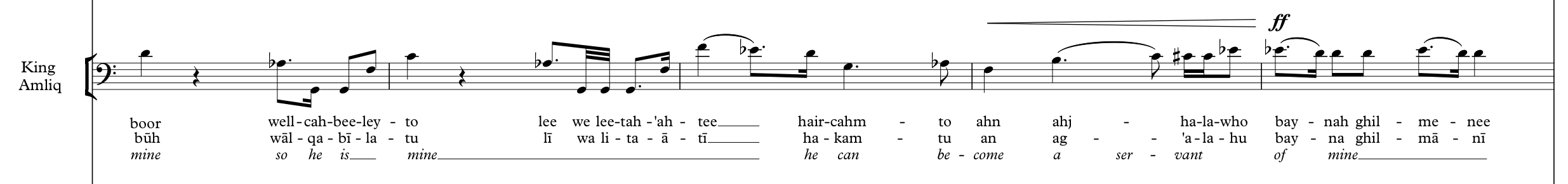

After a brief general pause, King Amliq emits his final verdict: their son will be enslaved at his court. The theme of tyranny comes back, and finally, we have an aria worthy of the king’s bass voice. His rage is expressed by huge intervals jumping up and down, a fiendish challenge for the singer.

Amliq and Hazila get into a duet/duel, the first adamant, the second desperate for what has just been deliberated. The king doesn’t like being contradicted and decides to humiliate the whole tribe, the full orchestra and choir together announcing the gravity of this decision. With a final recitative, Amliq states that no virgin from Jadīs shall marry unless he beds her first. The melody of this recitative is like a drill trying to break into the wall: small, contorted intervals followed by sudden jumps.

The scene closes with a slow chorale in the strings and solo winds.

Intermezzo — Quartet

This section depicts the preparations for the wedding between Afira and Naoufel, and is scored for four soloists (Afira, Naoufel, and two bridesmaids), choir and a delicate orchestral accompaniment. Such an ensemble eagerly welcomes a contrapuntal writing, and the result is simply stunning. We initially get the three female voices, echoed by the choir, and followed by Naoufel’s (tenor) solo. The melody paints ample arcs with its seventh jumps before falling again closer to where it started, in the best possible representation of a musical rainbow. Here’s a moment where the four voices sing together.

After a short duet between the soon-to-be-wed, the intermezzo closes with a poignant “Solo” for the concertmeister, whose beauty immediately echoed in my ears the first of the Four Last Songs by Richard Strauss.

Scene 3

The choir sings an equally joyful and furious dance motif, in 3/4 time, interspersed by 6/8 moments in the second bar of each 4-bar phrase. They joyfully call for the bride to be brought forward. An intimate love dance with just solo woodwinds, double bass and Arabic percussion briefly interrupts the dance, which then comes back before, suddenly, the theme of tyranny violently breaks in.

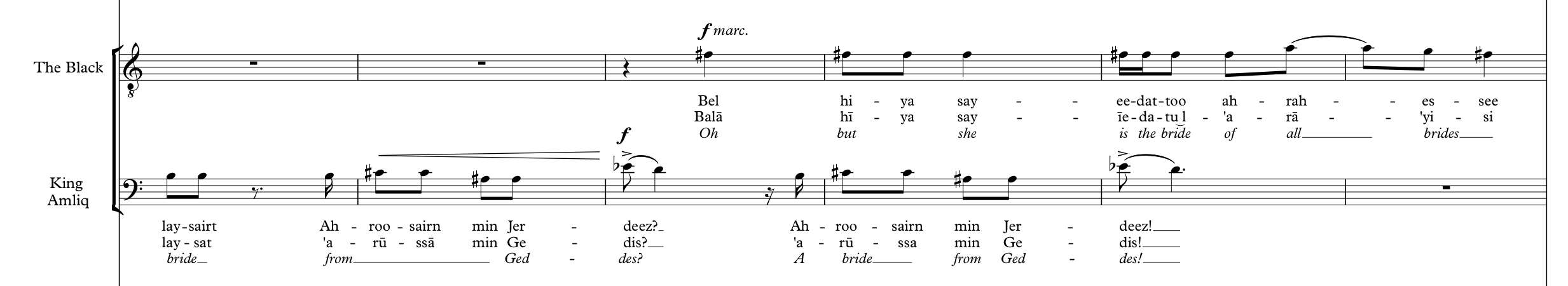

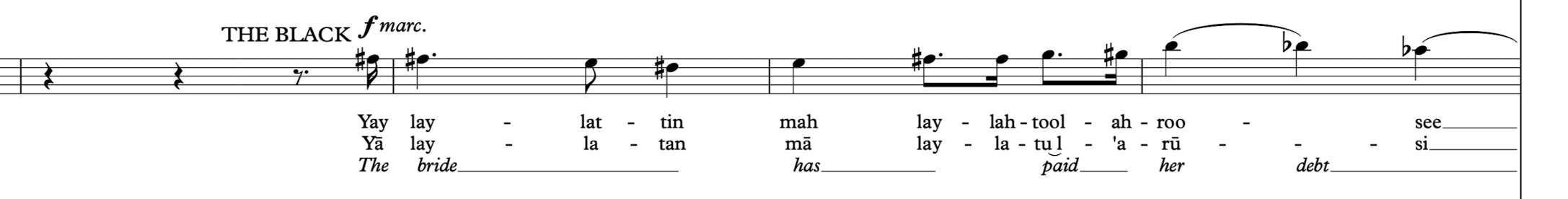

King Amliq has come with his soldiers to take Afira away. Almost ironically, the king sings the same “bring forth the bride” that the joyous choir was singing before. The contrast is cruel and powerful. Afira’s brother, The Black (Al Aswad) emerges from the crowd and engages in a duet with the king. The tension and desperation is palpable in the melodies, both moving in the smallest intervals.

The theme of tyranny comes to its climax when Amliq’s men (the male portion of the choir) engage in a tight formation and remind Al Aswad that the entire tribe will be slaughtered if they don’t submit.

The muted trumpet announces the upcoming recitative between Al Aswad and Amliq, where the first tries to challenge the second to a duel, but gets rejected. A minor 9th jump underlines Afira’s brother’s line “No humiliation shall pass!”. The worried tribe is then represented by the whole choir whispering among themselves.

With Afira taken away by Amliq’s soldiers, Zarqa comes back on stage with a heartbreaking lament accompanied by the solo cello:

The following aria sung by the blue-eyed mezzo-soprano seer is now replacing the 7ths with augmented 4ths over the words “eternal pain”. Only when she reflects on how her vision of heartbreak and tears came to reality, we get back to the bigger intervals. The divisi double-basses below, with slow glissandi and enriched ornaments, and reinforced by low timpani and bass drum, give these closing section an incredible dramatic power.

When the “Fanfare of the Dead” comes back, Zarqa’s melody almost assumes the rhythm of a gloomy Sarabande and, following that, a variation on the previous melody comes back. The lines of this aria are very long, and they never truly resolve their tension, making it a true challenge to sing and sustain, also because of its length (ca. 5 min).

Scene 4

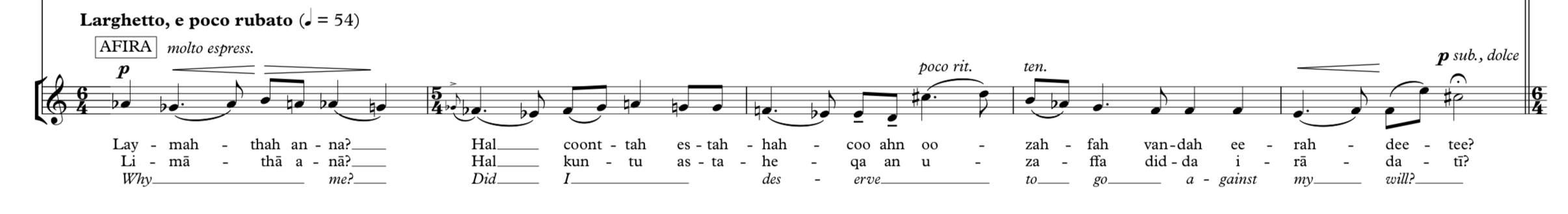

In the fourth scene, we witness to a broken Afira emerging from Amliq’s bedchambers, asking “Why me? Did I deserve to go against my will?”. Her sobbing and suffering is masterfully described by each bar of the melody being a phrase in itself. There are no long lines, as she cannot breathe for what has just happened. The continuous alternation of all kinds of intervals of a 2nd (minor, major, augmented) gives this a Turn of the Screw vibe. The more Afira sings, the more we suffer with her. The only two jumps—7ths, you guessed it—serve the purpose of painting her hopeless gasps for fresh air.

The solo woodwinds try to console her, but she keeps singing her desperation with chromatic ornamented descents. The final part of her aria is somewhat freer, and uses fragments of the octatonic scale, ending on a hopeful D-flat major.

The choir takes over, divided into two halves, one singing, the other staggering with a breathy whisper. The orchestra establishes a B-flat major carpet with the lowest instruments, contrasted only by the piccolo flute. What’s best for expressing darkness than pairing it with searing light?

Scene 5

In Scene 5, we see the rallying of the tribe by Hazila and Al Aswad. This is all supported by a furious rhythm in the Snare Drum and tremolos in the strings.

Hazila then starts singing, invoking the tribe’s honour. The C-sharp pedal in the strings describes the speechless crowd, standing there listening while Hazila tries to stir them with her expressive line.

“The Black” now joins, with a Tristan-like minor sixth expressing the shame he feels for the dishonour suffered by his sister. The “Desert Storm” element heard in Scene 1 comes back in the woodwinds to close this part of the scene.

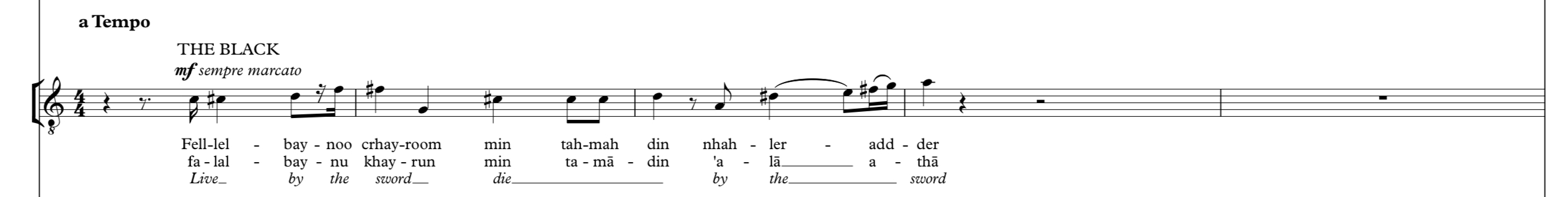

A solo on the trumpet, a development of the one heard before in the exchange between Amliq and Al Aswad, introduces the solo of the Jadīs nobleman. Al Aswad rallies the tribe for good, with a powerful march supporting his speech. Here’s the start of his line:

The upward jump of a 4th in the second bar gets swapped with an augmented 5th up followed by a perfect 5th down and a diminished 5th up, describing how “death is better than a life of shame”. The male choir then joins him, doubling the melody at the lower octave, for an immediate expansion of sound and dramatic depth. When the female portion of the choir joins, the focus shifts to their being worried about Amliq promising to annihilate them.

In a recitative accompanied only by low strings and solo trumpet, Al Aswad explains his plan to the tribe. His “they shall pay” gets a reaction by the strings which desperately gliss from and to an esachord (6-note chord: F-A flat-C-E-G-B) in different inversions.

The fury of the tribe comes alive in a powerful chorus with full scale orchestral accompaniment.

The scene closes with a duet recitative between Zarqa and Al Aswad where she tries, in vain, to convince him to rethink his decision.

Scene 6

The sixth scene opens with a solo of the Alto Flute exploring the thematic material surrounding the character of Zarqa. The Disappeared Arabs take over from off-stage, singing how Jadīs will be avenged. It is now time for Zarqa’s lament: she sees what is about to happen, and is heartbroken at not being able to do anything to prevent it. The melody is built upon this motif:

Dissonant intervals are built in a much smoother way this time, the only violent jump of a diminished 8ve underlining the “what moves swords harder than pride” in the text. Her line ends on a different disposition of the intervals found in the theme of tyranny: before we had D / E-flat / A, now we have C-flat / F / B-flat. In a sense, the final hour of King Amliq is getting near, but what Zarqa sees in her tribe’s future after that is not positive. Perhaps more suffering is awaiting them?

While the strings shift between A-flat minor and D-flat major, Hazila tries to understand what Zarqa means with her words. Her melody, in a G Lydian mode, expresses all the uncertainty and fear the still unforeseeable future brings upon them.

The choir, whispering in Sprechgesänge, depicts the tribe in the act of sharpening their swords, accompanied only by a gloomy gong in the distance.

A tense orchestral moment follows, after which the choir heard at the end of Scene 5 comes back. It is decided: Jadīs shall pay its tribute to Tasm, but on their terms.

Scene 7

The first part of this scene is occupied by the Jadīs tribe’s war dance. The 5/8 metre with an emphasis at the end of the bar gives way to the bloodthirsty energy that is rising on stage. The music repeats itself incessantly, almost like a trance, but one thing is certain: it is always growing, with more and more instruments joining at each new page. When the dance is over, Hazila approaches Zarqa asking what she sees, what she hears, and why that place is looming with fear. Her melody is almost a plainsong, expressing how tired she is of all this. The minor second interval of the beginning of her lullaby in Scene 2 can be heard here as well, an echo of the pain she feels for the loss of her son.

Zarqa replies that she hears death, tyranny, and disaster, that Tasm is not promised tomorrow, nor is Jadīs. Initially, the melody struggles to take off from its starting point (C) then, in a sudden major 6th burst, it escapes gravity and keeps rising towards the dreams she wishes she had heard about.

It then comes back to a lower register, with the word “death” described by an apparently innocent major 3rd, while “tyranny” and “disaster” use minor and major 2nds around the note D.

The scene—and the act—closes with an almost entirely chromatic ascent to C, with the orchestra playing a C-sharp / F-sharp / B / E-sharp quartal harmony chord, and the English Horn accompanying the closing of the curtain with an ornamented A-flat.

ACT 2

Scene 8

The second act opens with the feast-trap organised by the Jadīs to get revenge on Amliq and the Tasm. The winds play an initial iteration of the royal fanfare, the melodies intentionally written to be particularly hard for intonation—more on this in a bit.

In a duet-recitative, accompanied by the strings alone, Amliq notices Hazila and tells her that her son is dead. He then turns to address Al Aswad, and a duet between them ensues. We assist now at the most enthralling rhythmical moment of the opera, with an ostinato section in the low strings and bassoons to accompany the voices.

The winds, not shown in the picture, intervene with their enriched ornaments to keep the tension high. Both melodies refuse to engage in big intervals, instead moving in little steps, like a lion and a tiger circling each other, ready to pounce.

The choir—in the vests of Amliq’s court—joins the figurative battlefield, invoking the bride: Amliq wants to see Afira. When the high strings finally join, they give the signal for the new entrance of the royal fanfare, this time completely out of tune. The score itself states:

The Orchestra plays “out of tune”

So, it’s not a mistake!

We now hear the music which announced Afira’s entrance at the beginning of the opera. Over the same melody, she no longer sings “Zarqa” but “Amliq”, teasing how the king is a weakling now. She then gives the signal for her brother to get him. As we saw in the synopsis, violence is avoided onstage with the substitution of the massacre with the poisoning. Lastly, Afira convinces Al Aswad to spare Riyah’s life, since he is Zarqa’s brother.

The choir gets back, this time celebrating the victory of the Jadīs and the fulfilment of their revenge.

The low strings return with the “Desert Storm” melody, while the brasses introduce the theme of Al Aswad’s triumph. Afira’s brother, then, engages in a passionate aria:

It is a challenging line, all in the upper register, between D-sharp and B, continuously alternating half- and whole-steps. The few jumps (minor 6ths and 7ths), then, provide an even greater contrast. The theme of triumph is eventually taken by the choir, singing in fortissimo:

“Al Aswad” (The Black).

Then, suddenly, the choir switches role, back to the Disappeared Arabs, this time with a choral writing which is so different from anything we have just heard to cause a real shock. They try to warn the Jadīs that what they have just done will bear grave consequences.

Intermezzo & Scene 9

A short intermezzo ensues now, with Zarqa on stage with the little Nora accompanied by the ney flute and the oud. She sings a Hijeni, a kind of popular song that was used by camel riders to keep track of each other during the long overnight marches.

It is an innocent melody in what could be C minor, but these five notes are all those one will hear, leaving us in the darkness about what lies ahead.

The scene then switches to the desert storm Riyah is passing through to get to King Hassan of the Himyarite kingdom. The low strings and winds reiterate their quick gestures as if it were a warning of dire things to come. A steady percussion carpet drives us forward, while the melodic line is entrusted to the Bass Clarinet, which insists on a minor 7th (B / A). The high winds and strings attempt to gain the upper hand with short, bursty lines then, suddenly, all strings quote Zarqa’s melody, introducing the emerging of her brother Riyah from the storm.

He introduces himself to the Commander of the army with a melody echoing what the bass clarinet had kept repeating until then:

The rhythm becomes more frantic, underlining his conflicted emotions. He seeks revenge, but is also worried about hurting his sister, Zarqa. The seer’s theme (the minor 7th followed by ascending and descending 2nds) is constantly there in the strings, almost poking Riyah’s conscience.

As soon as he gets the commander’s attention, he engages in a recitative accompanied by cellos divided in six. There, he warns the army about Zarqa’s divinatory powers. Look at how the melodic material of the two characters intertwine here:

Scene 10

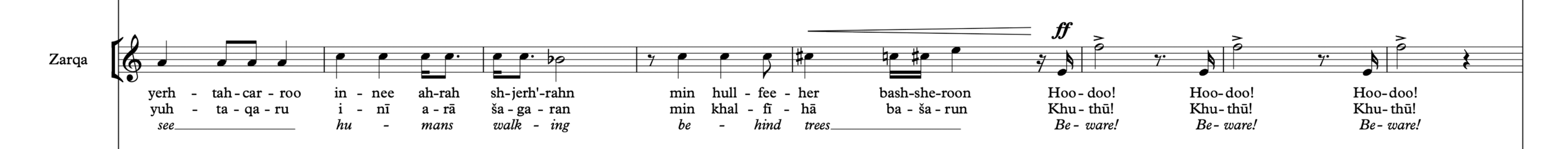

As predicted by Riyah, Zarqa sees the approaching army and tries to warn her tribe. She does so with desperate upbeat jumps, first in octaves, then in minor 9ths, on the word “Beware!”. In between these cries, her melody slowly rises chromatically, with a massive usage of “subito” dynamics and bursty crescendos.

Then, at the end, the jumps become diminished octaves, as if she were losing the strength to fight.

The solo trumpet once more announces the entrance of The Black. Curiously, now, the melody sung by the new ruler is extremely light, with a general air of indifference driven by his newfound pride. While the orchestra is clearly in 3/4, the voice—doubled by the first bassoon—proceeds in 6/8. We can see the recently appointed king, filled with hubris, looking down at Zarqa with contempt, not believing her. The woodwinds, in a trance-like movement, underline the general confusion reigning in the camp.

Zarqa gets back with her warning with renewed energy, this time once more with the minor 9ths—fiendishly difficult to sing in the required fortissimo dynamic. Back to Al Aswad, who still doesn’t believe the tribe’s seer. To be noticed now are the two bassoons proceeding in parallel fourths in a chromatic descending movement from A-flat to E-flat.

Both aware of the pointlessness of their efforts, Hazila and Zarqa engage in a poignant duet, accompanied by the winds alone with lines reminiscent of Stravinsky’s Firebird.

At the end of this duet, Hazila collapses to the ground.

Scene 11

This scene is introduced by the Alto Flute proposing Zarqa’s theme one more time. While Zarqa sings of her people’s hubris, Hazila quietly dies in her arms. The blue-eyed seer, therefore, intones a lullaby for her friend, whose words are just heart-rending:

Your eyes shine like stars saying goodbye to our land

The trombones join the strings in the accompaniment, with the PPP dynamic making their part extremely demanding.

This aria is roughly in ABA form, the first part moving in waves, and the second one starting on a G and coming back to that same note every four bars, as if a relentless clock were ticking down to the inevitable doom. This section ends on an eerily consonant B-flat minor chord.

What follows is, perhaps, the most incredible part of the opera. Even after listening to five rehearsals, when this played out in the premiere, I couldn’t hold the tears, it was just too much. The orchestration of this “Lullaby” consists of the entire cello section divided into four voices, the bass clarinet, and the choir (with the briefest interventions from the other strings). It is difficult to find the words to describe this, so I will let the score speak:

Each of the dark statements of the bass clarinet tells its story, with the low G-sharp alternating between bridge and arrival point. The octatonic movements, then, give the necessary uncertainty to support the drama that is unfolding on stage. The choir, then, enters the stage from the right, walking very slowly, and developing shivers-bringing harmonies. They sing of the dreams and memory that are accompanying Hazila in her eternal sleep and, with an ending in D major, we are encouraged to think that, eventually, all will be well. This, though, will have to wait a bit more, since we are about to witness the fury of destiny striking the tribe of Jadīs.

I honestly believe that this brief choir is a masterpiece, so much that I allowed myself to label it as the “Va’ Pensiero” of the Arab people. In Verdi, the choir sings of a people in chain; here, the chains of an endless and pointless cycle of revenge and pride are holding the Arab people down. History will tell whether I was right or not to make such a bold statement, but, for now, I know I will treasure this excerpt as one of the most incredible pieces of music ever written.

Scene 12

The last scene opens with a terrifying battle chorus, where the forces of the Himyarite king manage to surprise the Jadīs, slaughtering them all. Al Aswad is among the first to be cut down, and the ghosts of the dead Tasm rise to join the battle, ensuring vengeance is complete.

The orchestra in full force, and the choir, describe the battle in a furious 3/4 dance, the melody based on a B and paired with increasingly large intervals (a 5th, a minor 6th, a minor 7th), each one painting a mouth that opens wider and wider while it screams in horror every time stronger. The low instruments, instead, contrast this with chromatic movements, descending at first, then coming back up, with sudden 7th jumps.

A contrasting theme with just single woodwinds, whispering chorus, and low strings provides a short respite, but it actually represents the point of view of the Himyarite soldiers, looking around to check if anyone escaped the massacre. The first section then comes back on the words “The day has come”, ending with a fast run upwards in the high winds and strings (actually, cellos and basses are the only ones to run downwards).

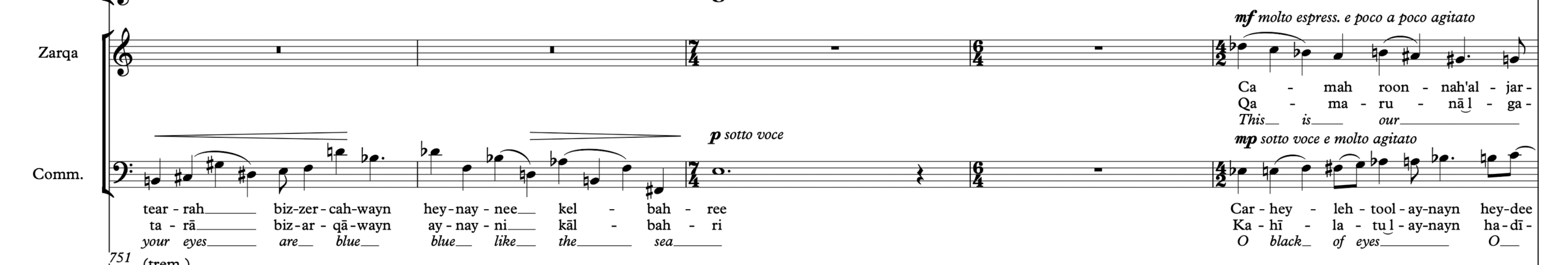

The curtain opens, and the “Commendatore” stalks through the dead, accompanied by Riyah. The low portion of the orchestra engages in an ostinato made up of the notes C-sharp | D | E | F | F-sharp, a gloomy tam-tam beat marking the steps of the commander. The “Fanfare of the Dead” is back in the trumpets, while the harp keeps plucking a high B that expands the range of the ostinato, and the choir, representing the ghosts of the dead Jadīs, whisper “We may be gone” from far, far away.

A duet between the Commander and Riyah ensues, with the first asking the second if the one he sees is indeed Zarqa, the seer. The commander sings only a low F-sharp, while Riyah shows the conflict tearing him apart by dwindling between a higher F-sharp and an F-natural, a half-step below. The expression instruction given to Riyah by the composer is, indeed, a “piano molto espressivo e doloroso”.

Zarqa, not at all intimidated by the presence of the Commander, points out to the moon, and begins singing “This is our moon, the last one you will see”. The melody descends octatonically, then jumps up a diminished octave, and again moves down alternating steps and half steps.

The ostinato in the orchestra has stopped, the texture now thick with counterpoint lines, almost trying to describe the inscrutable fog surrounding these characters. Tremolos begin in the strings, with the double basses exploiting their 5th string with the lowest possible C. The Commander replies to Zarqa, scared and mesmerised by her eyes at the same time. His voice rises and falls, torn by anger and admiration. The two melodies get then superposed, the resulting harmony so tense to almost dissolve into impalpable sand.

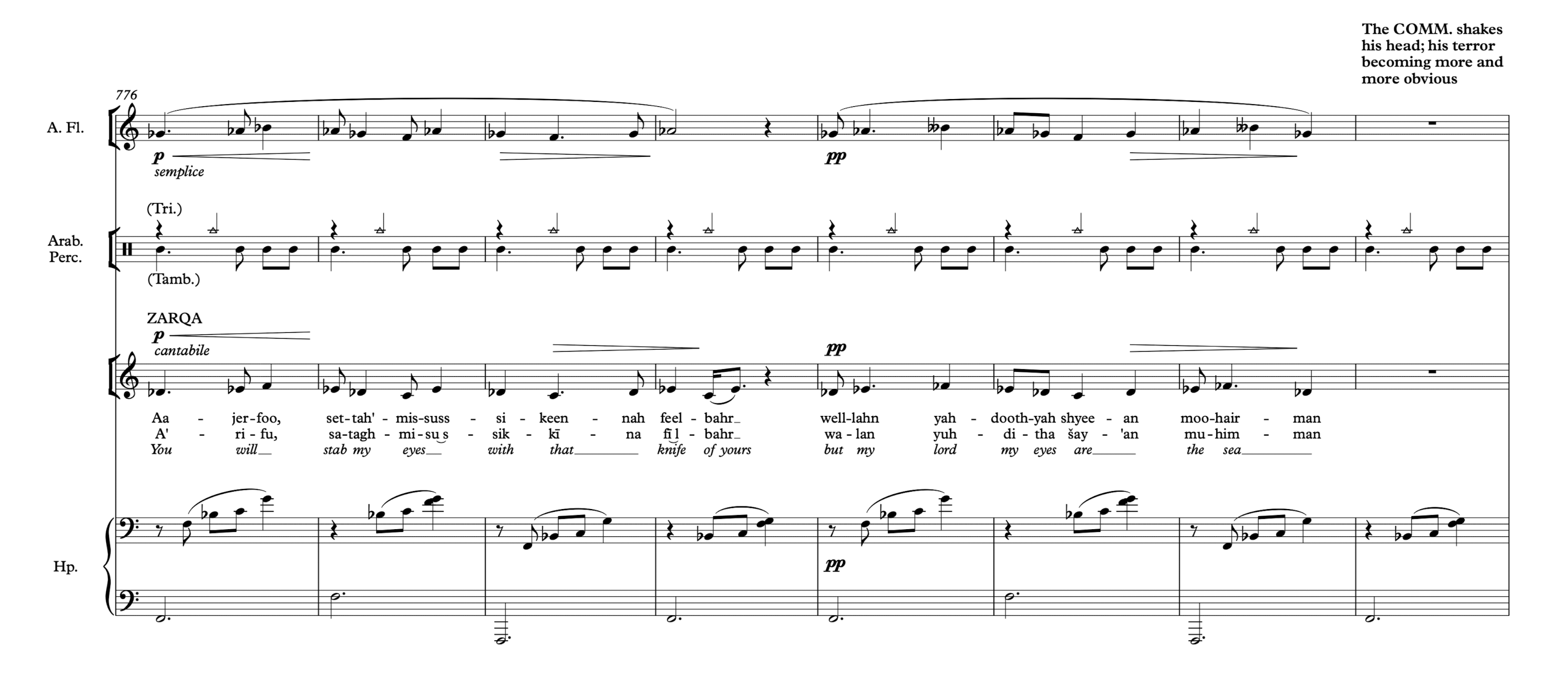

A short recitative follows, where Zarqa is warning the Commander about his upcoming death and making he react aggressively. Then, a mesmerising bolero begins, with just harp, Arabic percussion, and alto flute accompanying Zarqa.

More winds and pizzicato strings join, while Zarqa warns that her antimony will go to Afira, making her the new seer of the tribe. In a sudden general pause, the Commander, no longer able to stand the hardship of the prophecy, stabs Zarqa in her eyes. In her final moments, with the flute playing the seer’s theme, Zarqa anticipates the words of the Finale:

We may be gone, we shall go back to the land created for us, we survive for the dream.

While Afira takes the stibium and applies it on her eyes, the Alto Flute plays the notes with which she had begun the opera, closing the circle.

The Finale is a long solo line by Afira, or unique beauty, and set in 5/4 time and in an Aeolian B mode. The harmony is rich in added sixth chords and isolated clusters in the strings, and the emotional effect is stunning. Please refer to the end of the last episode for the full text of this Finale. After the initial accompaniment with just strings and flute, more instrument join, and the texture becomes thicker, denser, exactly when Afira encourages the Arab countries to be patient, that she hears weddings coming tomorrow.

On her final note, a high D, the choir joins, with the whole ensemble singing a B minor chord in all possible registers and inversions. A seventh (A) gets added to create tension but then, suddenly, the chord’s root B disappears, leaving just a glorious, positive, hopeful and, yes, relieved, D major! The opera started with a low A in the double-basses and, 100 minutes of music and drama later, the tension has resolved and found a home, or better yet, has found hope.

So ends Zarqa Al-Yamama, by Lee Bradshaw, the first grand opera of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. I hope you enjoyed this lengthy recount, but I even more wish you to get a chance to witness this masterpiece in person. For me, it has been an incredible journey, and it makes me feel like I have come full-circle from that day, thirteen years ago, when I realised I could not afford a degree in Opera Studies after my cello degree.

I would like to express my immense gratitude to everyone involved in this project, from the composer to the Artistic Director (Ivan Vukčević), from the Arabian Opera crew to each of the wonderful cast who made this miracle a reality. The Dresdner Sinfoniker, the Choir of Brno, the two conductors (Pablo Gonzalez & Nayer Nagui) were beyond excellent, and brought a positive energy to the stage.

Being in Riyadh for this event was an honour that cannot be described with words, and I will always keep everyone met there dear in my heart.

Thank you for traveling alongside me in this journey through time and music. Please let me know what your thoughts are, and get in touch, I would love to hear from you.

Until next time, thank you once again.

Michele

One thought on “Love prevails”