announcing the Trio for Piano, Violin, and Cello, Op. 180

This article is the second part of an expanded version of the Editorial Notes that can be found in the published edition. If you missed it, you can read the first part here. For the first time, this piece will be available exclusively in printed form until a publicly documented performance and a recording are realised. The edition will go into print in one month from today, to allow any interested sponsors to get in touch and be featured in the book.

A digital version will be released in 2025.

Pre-order the printed and digital version, plus get a PDF copy of these Editorial Notes for FREE here.

Videos of this piece can be found here: Allegro non troppo; Andante cantabile; Scherzo: Allegro non tanto – Trio – Scherzo; Finale: Allegro.

The Trio in E minor for Piano, Violin, and Cello — Op. 180

This Trio is a massive piece, lasting at least 32 minutes, and requiring impressive skills, especially from the piano player. Let’s not forget that the dedicatee of this work, Dotzauer’s eldest son Justus Friedrich Bernhard (Leipzig 1808 — Hamburg 1874), was a virtuoso pianist and professor of chamber music. The composer, therefore, was sure he could trust the skills of the pianist. The string parts are not easy by any mean, but they are a far cry from the piano one, confirming how comfortable and passioned Dotzauer was with the keyboard.

The piece is built upon the standard four-movement stamp used by Piano Trios (and Symphonies): a first movement in Sonata form (Allegro non troppo), a second, slower, movement in Lied form (Andante cantabile), a third, lighter, Scherzo and Trio (Allegro non tanto), and a closing fast movement (Allegro) again in Sonata form but using a fugue as main ingredient.

I. Allegro non troppo

The piece starts with a solo statement from the cello, in 3/4 metre, the piano joining immediately afterwards with a run in contrary motion octaves:

The violin promptly reacts, soon revealing how this was just an introduction to the real exposition of the main theme:

These three ideas get mixed, matched, and transformed in a two-periods-long modulating bridge, bringing us from the initial E minor to its relative, G major. This time, it is up to the violin to push the discourse forward:

The two strings swap roles in the next period, reinforcing the theme in the listener’s memory. A calmer, almost mystical coda section concludes the Exposition, with a final dominant seventh chord over B bringing us back to the beginning for the repeat. I believe this has to be played to avoid missing the origin of the material of the upcoming development, which is the starting triplet of the very first phrase.

With a surprise tonal shift, Dotzauer veers from the dominant of E minor to the key of C major, a typical Romantic modulation (VII/III solving on I).

As outlined in the excerpt above, all instruments are dancing around the opening triplets. From C major, we touch D minor (with a B natural from the descending Bach minor scale), E major, and finally F-sharp minor, this key persisting for longer, able to resist the lures of both B and C-sharp minor. The repeated triplet chords of the modulating bridge in the piano make a comeback while the strings chase each other as if they were in the stretti section of a fugue. This longer period contains brief modulations to B and E minor as a springboard to the A major of the next section, the first one to develop the melodic material of the main theme instead of the introductory triplets. The different ideas start to mix in a powerful, swirling concoction, first in A major, then in F-sharp minor once again, with the piano’s rolling arpeggios in contrary motion contrasting the strings’ melodic lines. The third instance of this new section explores D major and B minor, with lowered sixths obscuring the stormy waters we are sailing through. The time for smooth transitions is over, and we are now jumping from one key to another every two bars without any preparation. G, C, F-sharp (with a ninth chord!), and B major, sharply bring us back to E minor for the recapitulation.

The main theme returns unaltered while the modulating bridge—which should keep us in the home key—cannot help but yearn for something more luminous, resulting in the second theme changing course for the E major sea.

The Coda, very similar to the one in the exposition, could easily end the movement, but Dotzauer is not the same composer of the Two String Quartets, Op. 12 from forty years earlier, where he would throw away the conclusion, condemning the pieces to oblivion. This time, he has learned the lesson, and a più mosso section based on the opening triplets gives the movement the finishing touch it was missing. The closing melodic movement of both piano and violin paints an ascending major third, E | F-sharp | G-sharp, warning the listener that this is not over, and that our journey together has just begun.

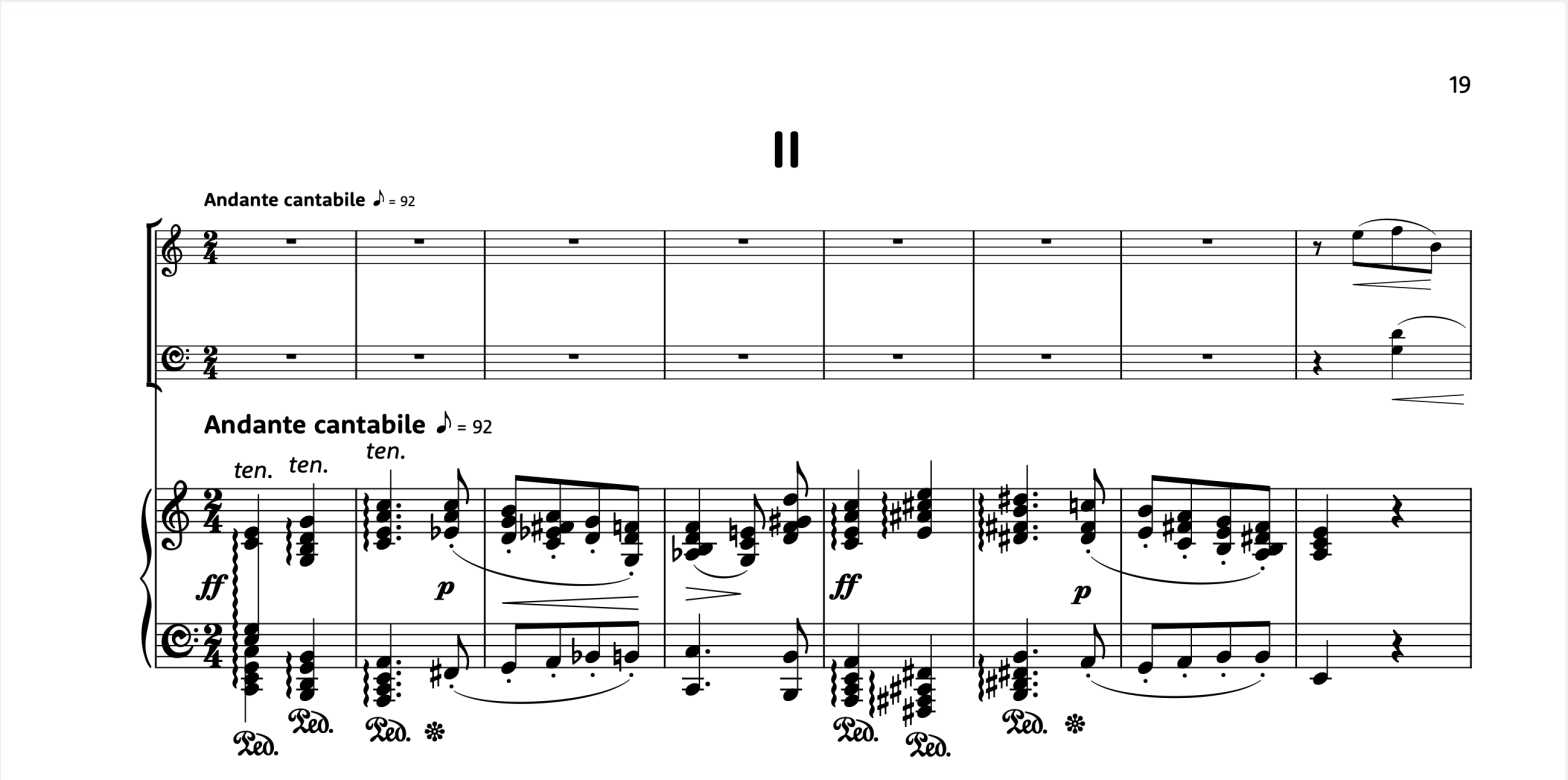

II. Andante cantabile.

The second movement is based around the key of C major (submediant of the main key), and starts with a solo exposition of the main theme—made up of an upward arpeggio followed by a melodic descent—in the piano. The V-IV cadence at the end of the phrase is a tell-tale sign of things to come.

The initial response of the strings is, sadly, quite banal, and fails to convey interest to a potentially engaging harmonic start. The piano continues its progression, veering towards A major (b. 17), D, G, and back to C major, the strings still refusing to engage, as if observing from afar.

The final C serves as a common tone for Part B, in A-flat major, where the strings now take the arpeggio and syncopated lines, the piano replying with nonchalance, giving a sense of three actors cautiously studying each other on stage. The texture slowly grows in intensity, as if the three had found some common ground to build their future upon—this being announced by a brief excursion into F major.

The A-flat that concludes this section, repeated as bell chimes by the right hand of the piano, becomes the major third (G-sharp) of Part C’s key, where a whole new world opens.

After an initial exposition of this new theme by the piano alone, the strings join in unison repeating the same line, accompanied by rebound chords in triplets (the F dynamic suggested in the piano should be carefully managed to avoid covering the strings). Another solo phrase in the piano part develops the new theme, promptly answered by the strings in the following period, still in parallel motion. The wait, though, is over, as the strings engage in an imitation duel where the cello follows the violin one bar later and a major seventh below, bringing also this part to a close with a soft E major chord in all instruments.

With no transition, we are brought back to C major with Part D (bb. 117-47), an ornamented version of Part A with a longer period that serves as a bridge to the closing section (E). The piano and the violin dance contrapuntally over delicate four-string arpeggios played by the cello, the first half of the period on a static C major pedal, and the second half on a descending fifth progression (A > D > G > C > F) pivoting on the final note to create a IV-V-I Perfect Cadence. The following period attempts a more variegated journey, starting from C major and visiting D-flat, E-flat, F, and G major in an ascending motion that lands on the most peaceful C major plateau. From there, we observe the calm after the storm, the gentle sun setting over the horizon, ready to sail towards new, uncharted seas.

III. Scherzo (Allegro non tanto) — Trio.

The opening phrase of the Scherzo, with the solo piano playing a contrapuntal realisation of the ascending E minor melodic scale, betrays early the imitative nature of this movement:

The strings join in the second period, alternating pizzicato and arco in perfect imitation. The cello then proposes a new melodic idea (in C major), immediately echoed by the violin and, successively, by the piano. A furious last period and a descending chromatic scale bring us back to the beginning with the canonical repeat.

The E that would have signalled the Tonic of the home key now represents the third of the Diminished Seventh chord of D minor with which the second part begins. The ascending scale is, this time, scattered between the instruments: E-F (natural) in the piano, G-A in the cello, C-D in the violin, and D-E in the piano once more. Now, though, we have moved from D minor to C major through a series of modulations by thirds: F minor, A minor, C major.

We cannot stop here, though: the C major deceptively peaceful chord gives way to another Diminished Seventh of B minor, which serves as a reprise of the previous melodic idea in the major mode. This is not a development, ready to go elsewhere, though, since the violent, diminished chords are back, this time pushing us towards a C-sharp minor which is not allowed to survive even one bar, immediately assuming the role of F-sharp’s Dominant. This triggers a domino effect that avalanches downhill through B, E, A, and D major, this last one becoming the Subdominant of a Perfect Cadence to A major.

A new progression ensues, driven forward by the melodic idea previously proposed by the cello and based on a peculiar harmonic progression: I — V — iii — V/V, ending on the minor Tonic of the key based on the Dominant. Thus, from A major, we jump to E, B, F-sharp, and finally to C-sharp minor. An extended pedal on the Dominant of E minor (B) allows the tension to ease enough to prepare the listener for the recapitulation of the initial theme.

The final two periods of the Scherzo are furiously trying to reach the home key, with G major and A minor trying to delay the inevitable as much as possible.

The Trio, based in the key of E major, is, surprisingly, in waltz form, and employs the mechanism of the “infinite screw” to fuel its harmonic structure. Already in the first period, where the cello plays a descending chromatic melody and the piano accompanies, we move through four keys: E major, G minor, F-sharp minor, and F minor.

The second period introduces a short melodic idea, performed in imitation between the strings, with the violin then taking the lead with broken chords lines. Here we have three micro-sections: the first modulating every bar (B-E-A-D), the second and third firmly settled in C-sharp minor. The final Tonic is followed by the Dominant of E major, bringing us back to the beginning through the repeat. We had not seen any melodic triplet since the first movement, and yet here they are, in the piano’s arpeggiated chords, serving as a connection throughout the piece. The second ending of Part A, while using the same bass note (B), modulates from C-sharp minor to A major, where the cello proposes a new descending chromatic line, the piano takes the violin’s broken chords over, and the violin replies to the cello with an ascending line.

In Part B, the cello’s chromatic line lasts only four bars before passing to the other string in another key. To the A major offered by the cello, the violin reacts with B major, always with an ambitious chord progression: I – V – V/IV – IV | modulation | augmented 6th resolving on the new Tonic. To the C-sharp major offered by the cello, the violin replies with D-sharp major; the last chord, though, is a Dominant of C-sharp which, through a Deceptive Cadence, brings us back to A major. This has a peculiar effect, as though we had circled in a loop all this time, covering a considerable distance without apparently going anywhere.

The next period, dominated by the only truly melodic line of the movement, serves as a bridge towards a sort of recapitulation, this time apparently in B major. The stability is not to last, though, and while the violin and cello ride chromatic waves, the piano profits from almost improvising on them, covering the following keys in Tonic-Dominant chunks: B and B-flat major, then A, G-sharp, and G minor, the Dominant of which, a D major chord, is followed by a Dominant of C-sharp major!

The melodic broken chords come back, now in the cello for the first time, with the violin answering in melodic octaves and the piano offering a steady rhythmical structure. From C-sharp, we descend to B major, A and F-sharp minor, and, suddenly, back to E major: home was just around the corner, after all. The conclusion—leading to the repeat of the second part—is, and surprisingly after all these fireworks, quite soft and calm, the first ending adding contrary motion to the piano triplets as it goes back to A major. The second ending, instead, is made up of three bars of E major Tonic, followed by a “General-Pause” bar. The Scherzo, without repeats, can now be brought back on stage.

Bottom Line

Thank you for reading so far.

Be sure to subscribe to the blog to be notified of the publication of the next episodes.

See you here very soon!