announcing the Trio for Piano, Violin, and Cello, Op. 180

This article is the third and final part of an expanded version of the Editorial Notes that can be found in the published edition. If you missed them, you can read the first part here, and the second part here. For the first time, this piece will be available exclusively in printed form until a publicly documented performance and a recording are realised. The edition will go into print in one month from today, to allow any interested sponsors to get in touch and be featured in the book.

A digital version will be released in 2025.

Pre-order the printed and digital version, plus get a PDF copy of these Editorial Notes for FREE here.

Videos of this piece can be found here: Allegro non troppo; Andante cantabile; Scherzo: Allegro non tanto – Trio – Scherzo; Finale: Allegro.

The Trio in E minor for Piano, Violin, and Cello — Op. 180 (cont’d)

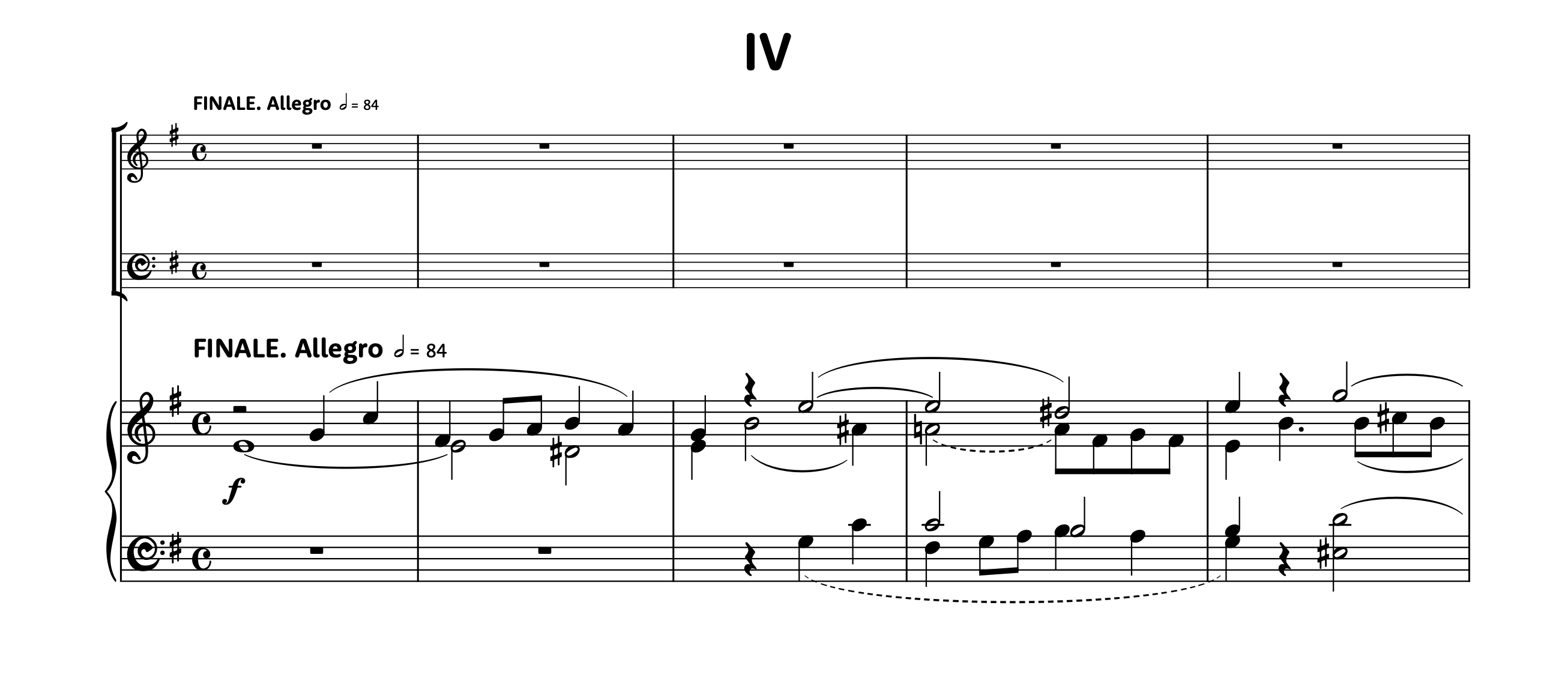

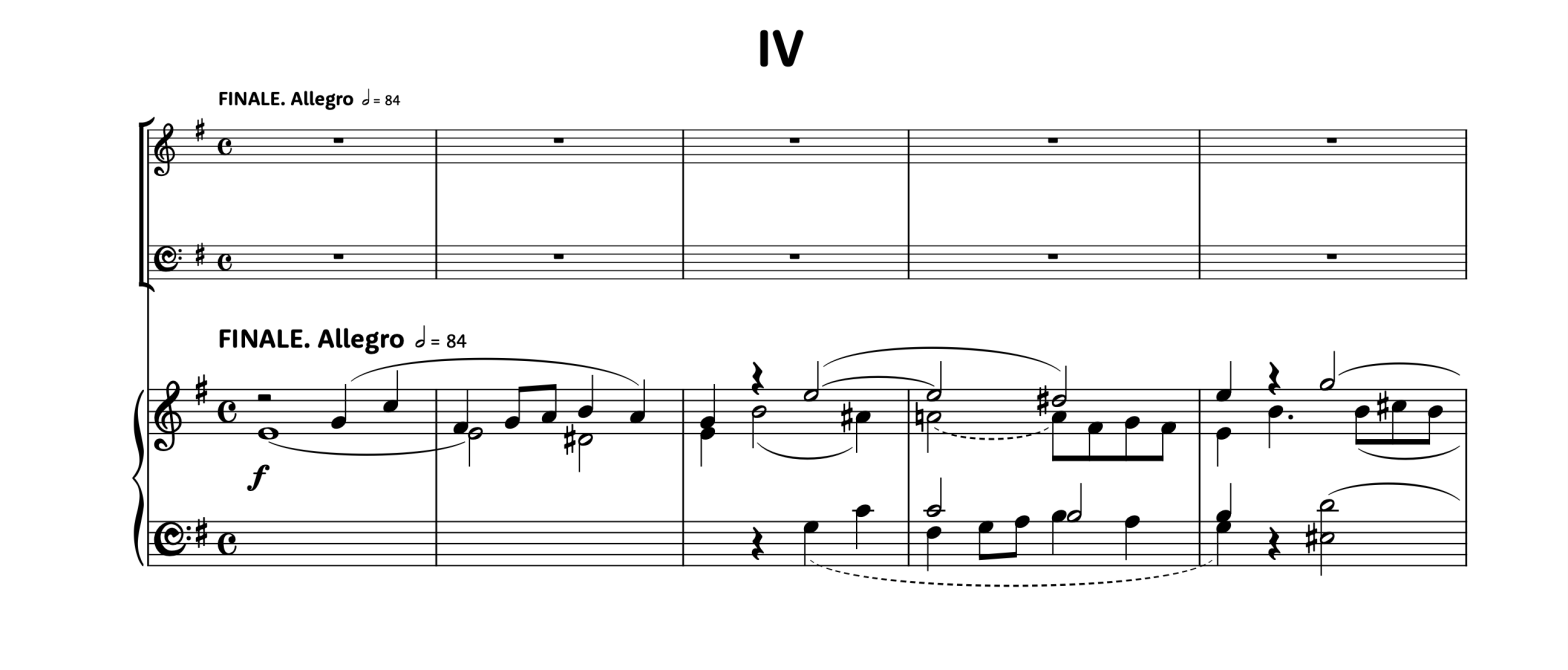

IV. Finale. Allegro

The last movement is what Dotzauer has reserved his best cards for: it is an Allegro in common time with a fast metronome mark that specifies the rate of a minim instead of that of a crotchet. I do not think it is a mistake, though, as the rhythms employed are often short enough to justify Dotzauer’s choice.

The opening period that precedes the exposition of the main theme of this Sonata form is a fugue, where its elements are already closely intertwined from the very beginning.

The violin and the cello join the fray, playing hide-and-seek with the material offered from the piano until it is time for the violin to take the lead.

It is a playful melody of elementary form and structure, accompanied by the steady chords of the piano. This first phrase is then immediately repeated by the piano, with the cello closely chasing in imitation. The violin is again trusted with the task of building a bridge towards the second theme, opting for a V-IV-V cadence already in the first bar of the transition. With powerful scales in octaves and contrary motion, the piano accepts the challenge and paints its version of this scene, with the cello singing a proud and contrasting bass line alongside. Then, the piano alone adds two bars of chords to create a suspended cadence and a fermata that halts everything. What will happen now? Something new? A repeat? Neither of them, as what follows is a re-exposition of the initial fugal theme in the strings alone. The second phrase, though, deviates towards G major, where the piano joins for the final period of this bridge. Here we get the last return of the fugue, this time harmonically enriched by the strings’ lines. The G major key is confirmed and reinforced by several excursions into neighbouring keys: E-flat major (lowered VI), Diminished Seventh of the Dominant, followed by a continuous alternation between the Dominant (D) and a resolution in minor mode. A last chordal progression in the piano’s right hand (vi – V – vii°/V – V – I – V/V – V) introduces the second theme, while the left hand plays a Dominant pedal (D).

The chant of the secondary theme, in G major, is entrusted to the cello, with only the piano accompanying through chords alternating between the two hands.

The whole phrase ends with a perfect cadence in B minor, but the violin doesn’t buy it, and insists in repeating the unaltered first part of the theme. The cello immediately engages in a contrapuntal battle, and the violin is obliged to change course to stay in G major. The piano is given its chance to express its perspective on this theme, proposing several modulating ideas while eventually coming back home with an ascending and descending scale in octaves where the triplet element tentatively peeps round the door.

The next section is based exactly on those triplets: is it a third theme, or just the coda of the exposition? Whatever the case, it is one of the more harmonically intense moments of the entire piece, where even the “infinite screw” found in the Trio of the third movement managed to find its way here.

This whole period is repeated twice, with the strings engaging in complex chordal polyphony and the piano experimenting with different triplet configurations within the same harmonic path, eventually leading us towards E major. Contrary motion arpeggios in triplets in the piano, accompanied by ever more serrated syncopated chords in the strings, and followed by a chromatic descent, open the way towards the Development section, which begins with the main theme in the new major key. The melody is sung by the violin, but the cello immediately answers half-a-bar later with a stricter counterpoint, closely followed by the piano. The three instruments dance and swirl with and around each other, proposing, answering, falling back, pushing forward, until the theme of the bridge suddenly erupts in E minor.

At first, the violin engages with the cello in a high-register duel, then the cello rejects its previous partner for the piano, relegating the fiddle to a low-register accompaniment that almost sounds as a clear provocation. The violin, though, doesn’t appear to be willing to play along: this period, in fact, is cut short to seven bars, with a fermata at the end, and on a suspended cadence. What comes next is at best unexpected because it is a third reprise of the introductory fugue, this time in C major, by the violin and cello alone. The initial period is followed closely by the piano, summarising with two hands what had just been proposed by the strings. The fugal dance then continues in A minor, first in the piano, then in the strings, with a final deceptive cadence (E-F natural) introducing the final period of this development, in a short three-voice invention in the piano alone that twists the mode into major.

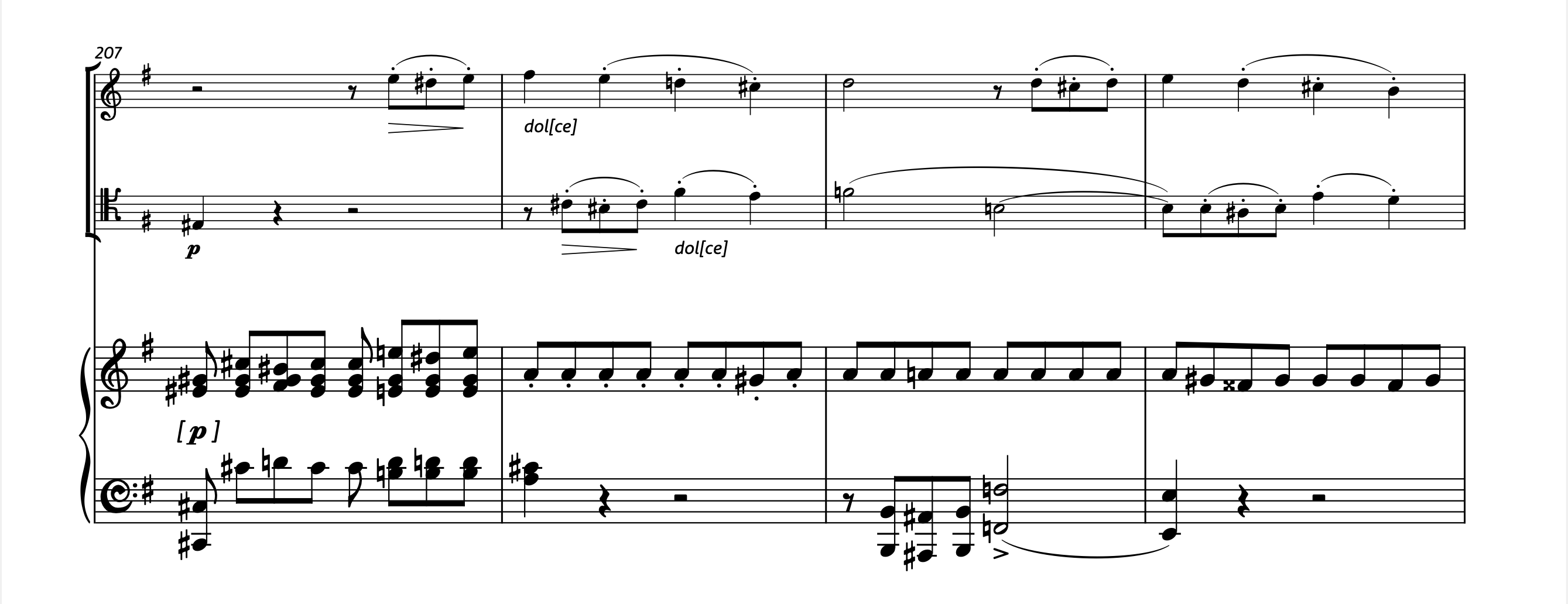

The Recapitulation kicks in with the main theme in A major, a striking contrast in character from its first appearance at the beginning of the movement (in E minor). This section will contain four periods based on the same idea, each time with a different accompaniment style or contrapuntal structure. The first period is entrusted to the singing voice of the cello accompanied by broken chords in the piano rich in secondary and tertiary dominants, and apparently ending in C-sharp major. The violin now takes the lead with the melody still in A major, the cello replying contrapuntally half-a-bar later, and the piano imitating the theme’s upbeat with the left hand while playing repeated single notes in the right one.

The second half of the period veers towards new tonal shores, pivoting through the Dominant of F major to somehow get to B minor, the third period’s key. The piano plays the main theme with the right hand and enriches it with fast arpeggios in triplets; the violin and cello can only punctuate this density with short bits of the melody’s beginning portion. The deceptive cadence at the end of the first phrase allows the modulation to G major, and the same structure will thrice repeat with modulations to E minor and C major. The final deceptive cadence is what modern business language would define “the composer’s exit strategy”, with this new twelve-bar bridge now based in A-flat major.

The whole ensemble plays FF, the violin in descending arpeggios, the cello in arpeggiated chords, the piano performing a guitar-like accompaniment in the left hand and a chromatic variation of the main theme in the treble. The violin picks up the A-flat from the piano and changes it enharmonically to G-sharp to slingshot the harmony into a C-sharp major/minor full-of-pathos and drama. I am not aware of what kind of hands did Bernhard Dotzauer have, but here is the only spot in the piece which appears to be (almost) unplayable (b 241): fast triplets in octaves jumping up and down in contrary motions in the two hands. A much simpler solution with a similar if not equivalent sound signature might be possible. A long fermata on an unison G-sharp, followed by a double barline, and a key signature change to E major, introduces us to the recapitulation of the secondary theme.

Compared to the Exposition, the violin goes first here, accompanied only by the piano, while the cello goes second, accompanied by the contrapuntal line of the violin, and with the piano playing alternated chords throughout. The same coda heard before makes a comeback in major mode, but the true surprise is the key signature change back to E minor that follows. For the next two pages (bb 276-91), the piano doesn’t play anything else than triplets in either arpeggios or octaves. The violin and cello reply with syncopated chords and polyphonic double-stops in the first period and with dotted rhythms in the second.

The main theme makes a final try to come back on stage but is pushed away by the return of the opening fugue, this time orchestrated over the three instruments. This lasts only four bars, though, and the piano’s triplets, coupled with the strings’ chords, give a gloomy end to this monumental piece. The closing cadence is peculiar, with a Dominant of the Subdominant, a major Subdominant, and a minor one to give a Plagal cadence conclusion to E minor. May Dotzauer have forgotten Johann Sebastian Bach’s lesson that no contrapuntal piece may end in minor? We may never know and, perhaps, it is better to leave this question an open-ended one.

About this edition

This edition is based on the only surviving source from F. E. C. Leuckart (Constantin Sander), plate number FECL 2585. No autograph has been found so far.

Several edits have been necessary: the few supposed wrong notes have been marked with their corrected equivalent in square brackets or with ficta accidentals outside the stave to mark a possible oversight. Whenever articulation or slur structures were thought to have been omitted to save vertical space—or simply time and ink—they have been marked either in dashed typeface or with the addition of the word “sim.” in square brackets. A few gradual dynamics were marked incoherently between the instruments, often due to the lack of vertical space—the full score being extremely packed. They have all been uniformed and a note has been left in the appendix.

The Critical Notes section includes the over two hundred remarks that have been found during the fifteen-months-long preparation of this edition. The final edition includes this volume and the two separated string parts.

I would like to thank all those who made this edition possible, from the personnel of the New York City Public Library to the composers and performers who have listened to this piece and shared their invaluable opinion during the construction phase. Finally, I would like to thank Swiss composer William Blank for his in-depth aural analysis of the piece and for sharing his enlightening view on Dotzauer’s surprising and unexpected style.

I hope that this piece will be allowed to find its way back into concert halls and recording studios, where—in my humble opinion—it rightly belongs.

The Editor

Michele Galvagno

Belgrade, Serbia — September 8th, 2024 (updated and prepared for web publishing on September 30th, 2024)

One thought on “Dotzauer Project — Episode 12 – Part 3”