announcing the publication of Carl Schuberth’s Souvenir de la Hollande, Op. 3, for Cello and Piano

This article is an expanded version of the Editorial Notes that can be found in the published edition, available digitally here or here. A promotional video can be watched here. The printed version will become available during the Spring.

EDITORIAL NOTES

Introduction

Carl Eduard Schuberth (Magdeburg, 1811 – Zurich, 1863) is considered one of the most talented students of Justus Johann Friedrich Dotzauer (1783–1860), the eminent German cellist and pedagogue, father of the Dresden Cello School. In 1833, the young Carl set out to conquer the European stages with only this solid training and his enthusiasm.

At the beginning of 1836, following a particularly notable concert in Saint Petersburg, he was appointed ‘concert cellist’ at the Court Orchestra and at the Imperial Theater. This is how his long and successful career in Russia began. During the following 27 years, Schuberth fulfilled his duties as soloist, quartet player, teacher, conductor, and composer.

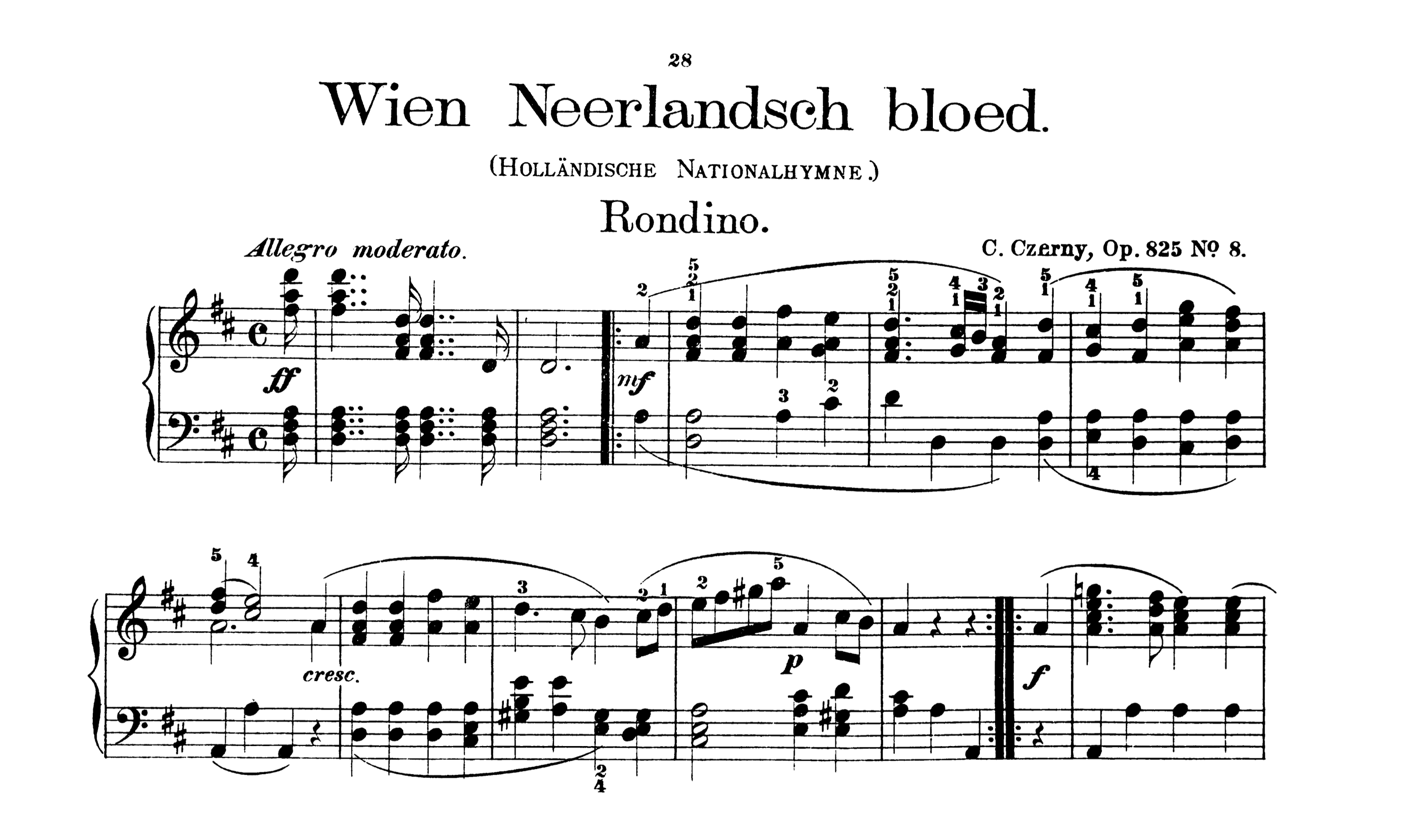

But let’s come to the story of his Opus 3, composed around 1829 but first published in 1836, titled (from the first edition’s cover) “Souvenir de la Hollande | Fantasie et Variations brillantes | sur un Thême national hollandais | pour le | Violoncelle | avec | Accompagnement de l’Orchestre | ou de Pianoforte.” The work is inspired by an old popular song titled, in Dutch language, “Wien Neêrlandsch bloed in de aders vloeit” (Whose Dutch blood flows in the veins), composed by the Dutch-German composer Johann Wilhelm Wilms (1772–1847) on text by Hendrik Tollens (1780–1856). It served as the national anthem of the Kingdom of the Netherlands from its foundation in 1815 until 1932. Here is its incipit:

The theme was quite in vogue at the time, with the great pianist Carl Czerny (1791–1857) using it for n° 8 of his Amusement des jeunes amateurs, Op. 825, for piano, first published in 1853.

The fantasy and variations composed by Carl Schuberth for cello and orchestra (or piano), constitute an eminently virtuoso work and, being composed at the dawn of his career, proved to be crucial to his success. His brother Julius (1804–75), publisher in Leipzig and Hamburg, reported how this composition aroused extraordinary enthusiasm during his European tours from 1833 to 1835. Its performances in Holland in 1834-35 even earned him the title of “Honorary Cellist to His Majesty the King of the Netherlands”. The work was composed and dedicated to Her Majesty the Queen of the Netherlands, and he received from her a diamond ring worth 1000 florins (approximately 40,000 euros today). During a visit to London in 1835 he also ousted his colleague Adrien-François Servais (1807–66) during a musical ‘joust’ organised for the birthday of His Majesty the King (William IV, father of Queen Victoria) at the Palace of Saint-James. As we already mentioned, it was the performance of this piece in 1836 that earned him his engagement with the Court Orchestra and the Imperial Theater of Saint Petersburg.

Carl Schuberth’s performances were reported in numerous musical publications of the time, the critics pointing out that the virtuosity, but also the commitment of the artist, literally transported the audience and triggered ‘thunderous applause’ and multiple encores.

This evening was a new triumph for Mr. Schuberth; his Variations on a National Theme electrified the large audience.1

As fate would have it, this work fell into oblivion, but following the recent discovery of an original score in an antique dealer, a new life is taking shape. This would only be fair to Carl Schuberth, considered the legitimate founder of the Russian Cello School and one of the founding fathers of the Russian musical Society and the St. Petersburg Conservatory.

The Souvenir de la Hollande for Cello and Piano

This fantasy is composed in the form of an introduction, followed by J. W. Wilms’s theme with three variations, and capped by a long recitativo and a closing Allegro. The main key is D major, a most comfortable and sonorous key for the cello, with only the recitativo switching to D minor. It is clear from the first look at the score that Schuberth conceived this piece originally for cello and orchestra, with “Solo” and “Tutti” markings and instrumental cues in the piano part, alongside the doubling of the orchestral basses in the “Tutti” sections in the soloist part.

The Introduction2 has two entire periods based on a Dominant pedal (A), with the cello entering the stage with a lyrical line painted with an ascending major sixth followed by a descending scale. Only after the first period, where the cello flexed its muscles with embellished runs, we get a glimpse of the theme, as much as the author tried to conceal it:

A sudden shift to B minor (b 34) shrouds the scene under tempestuous clouds, until the piano answers to an F-sharp major chord (Dominant of B minor) with an A major with added seventh (Dominant of D) chord, breaking the siege of darkness with the rays of a sunny D major.

A short cadenza introduces the main Theme, marked Andante, in common time with a quarter-note upbeat:

The theme itself is of the utmost simplicity, with no internal modulation and with a clear path from Tonic to Dominant and back to the Tonic. The theme and each of its variations are followed by an orchestral tutti, here reduced for piano.

The First Variation starts with a jété gesture from the cello, followed by an impressive mixture of some of the most complex techniques the instrument has to offer. From sudden changes of register to octave runs, the first period quickly flies by, followed by a second one which the composer decides to repeat twice—all following variations will share this updated form. The variation closes with a fast ascending scale in artificial harmonics, followed by the orchestral “Tutti” adding four extra bars of Dominant pedal at the beginning.

The Second Variation is marked Più lento (slower), with the piano developing the thematic line and the cello starting from its lowest register. The “fantasy” character is glaring here, since there is not a single and clear melodic idea developing throughout that can be followed. Rather, there are short excerpts in different techniques joined—almost stitched—together, the main goal being to show the performer’s abilities. The second part of the variation is built upon the melodic idea of the introduction and only briefly mentions the end of the first phrase of the main theme. The “Tutti” then returns, with a Tempo I marking signalling the recovery of the initial pace.

The form of the Third Variation changes structure again, with both parts now bearing a repeat. This time, Schuberth focuses on arpeggios and jété gestures, which he marks with “tiré”. This could have been a deformation of the French “tirer”, down-bow, since more often than not the jété technique is performed by pulling. Given the complexity of the solo part, though, this would hardly be the most serious quandary. The second half of the variation focuses on three- and four-strings arpeggios, with the piano singing the second part of the theme. A short cadenza follows, with the cello performing a descending chromatic scale in ricochet, and exiting with an alternation of bowed and left-hand pizzicato notes. The descending scale has different notes in the cello and in the piano part—which doesn’t show a cue staff for the solo part; sadly, both options appear to be riddled with errors, and an editorial proposal has been added as an Ossia staff above. The jété line comes back, with a descending arpeggio welcoming the orchestral “Tutti”.

The Recitativo imitates the equally named form used in operas, where the singing line proceeds alone, interspersed with chords from the orchestra or piano in appropriate points. This scene requires the greatest virtuosity from the performer, especially in bow management. It is set in D minor, subsequently visiting B-flat major and, with a tense French augmented 6th chord (E-flat | G | A | C-sharp), we are brought back to D major, not without feigning a visit to F major. The flageolets of the cello, doubled by flutes and clarinets, welcome back the main theme, entirely presented in artificial harmonics.

The trumpets’ call announces that the finish line is in sight, with a long “Tutti” section (Allegro) where the main theme is presented one last time. The solo part is now ready for the final fireworks, with ornaments, double stops of every kind, and, if all this were not enough, broken octaves in irregular patterns. There is also time for a few “jété” strokes and a final scale in artificial harmonics to seal the package. It is no wonder that this piece caused so much enthusiasm in the audience of the time: it is masterfully written with a single goal in mind, that is, to explosively and spectacularly show off everything the cello has to offer.

Building a modern edition

The sources used to reconstruct this edition were the following:

- R-Vc: solo cello part of the reduction for cello and piano, from the Schuberth & Niemeyer edition (published 1836), plate number 178. There are at least three copies of this, and they have been checked to be the same.

- R-Pno: separated piano part of the reduction for cello and piano. Same as above.

- Or-P: set of orchestral parts for the cello and orchestra version, curiously with the same plate number as R-Vc/Pno. This copy, kindly provided by the Badische Landes-Bibliothek in Karlsruhe, Germany3, contains 15 parts (1.2.2.2. — 2.2.0.0. — Timp. — Solo Vc. — Strings). The strings parts have handwritten music paper inserts stitched with metal brackets in correspondence to certain “Tutti” sections. It has been so far impossible to date these inserts. They contain the part string players need to play when performing without winds or in a string quartet formation, and they integrate what was already written by the composer.

The cover states that three versions of the piece were published: one with piano accompaniment, one with orchestral accompaniment, and one with string quartet. As it was customary at the time, the quartet players would perform from the same orchestral string parts, enriched by the composer with cues from the other instruments. In this case, cues would not be there to help the orchestral player know what happens around, rather as an alternative to be played in case winds were not available. This practice was abundantly used until well into the second half of the XIX century.

About this edition

Unfortunately, the incoherence between the sources—even when belonging to the same publisher and printing run—were much higher than what was usually found in other scores of the same period. The highest number of discrepancies was found among the orchestral parts (Or-P) where, for example, a FZ dynamic marking would be used interchangeably with an SF or an accent articulation. Source R-Vc had different notes in the “Tutti” compared to both the left-hand of the piano and the “Violoncello e Basso” part. This specific mistake has been corrected without further notice, while every other issue has been listed in the Critical Notes section at the end of the present volume. When correcting a clear mistake, notes have been enclosed in square brackets and slurs/ties drawn using dashed typeface. The solo cello part is almost devoid of dynamics, some of which have been added as suggestions in square brackets, taking inspiration from the piano part.

The present publishing initiative aims to reproduce exactly the composer’s original intent. This volume contains the score of the cello and piano version, alongside a separate cello part. Later in 2025, the full orchestral score, the performance material, and the string quartet version will be released to complete the cycle.

Acknowledgements

My deepest thanks go to Michel Schuberth, direct descendant of the composer, for providing invaluable insight over his ancestor’s work, life, and production. This edition would have never seen the light of day without his contribution and encouragement.

An honourable mention goes to the Badische Landes-Bibliothek in Karlsruhe, Germany, for kindly agreeing to digitise the orchestral source in their collection.

We hope you will enjoy rediscovering Carl Schuberth’s works as much as it has been an honour to unearth this unfairly forgotten gem.

The Editor,

Michele Galvagno

Saluzzo, Italy — February 15, 2025.

- Journal de La Haye, January 28, 1835 issue, in French. Report on the 5th concert given by the company l’Harmonie. ↩

- The source doesn’t write “Introduction” as a title at the beginning. This has been added as an editorial contribution in Italian language, in coherence with the rest of the headings. ↩

- Souvenir de la Hollande : Fantaisie et variations brillantes sur un thême national hollandais pour le violoncelle avec accompagnement de l’orchestre ou de pianoforte; oeuv. 3 / composées … par Charles Schuberth. Shelfmark: DonMusDr 2565. Accessible from this URL: https://digital.blb-karlsruhe.de/id/6795084. ↩

2 thoughts on “The Dresden Cello School — Episode 2”