Announcing the Scales and Exercises, Appendix 1 of the Violoncello School, [Op. 65]

This article is an expanded version of the Editorial Notes that can be found in the published edition, available as a printed book (coming Fall 2025) as well as digitally (PayPal/Stripe — Apple Pay/Credit card). Five promotional videos have been realised for this edition and they can be watched here (No 22, No 26, No 28, No 30, No 47), and you can expect several videos from me explaining these exercises in great detail.

EDITORIAL NOTES

The missing link

When, in the first months of 1824, the then 41-year-old Justus Johann Friedrich Dotzauer, accomplished cellist and pedagogue, sent the manuscript of his just completed Violoncello-Schule to the publisher Schott in Leipzig, he must have felt troubled and hopeful at the same time. Troubled because this was his largest work so far, and so extensive that both printing costs and final retail price risked rendering it inaccessible. Hopeful because he knew within himself that this creation had the potential of altering cello playing and teaching in profound ways.

The proliferation of cello methods during Dotzauer’s lifetime reflected two concurrent developments: the instrument’s growing popularity among amateur musicians, and the rapidly evolving musical aesthetics of the late Classical period, which demanded increasingly sophisticated pedagogical approaches.

The two main sources that inspired Dotzauer to write his first Violoncello School both originated in France: the so-called Methode du Conservatoire from 18041 and Jean-Louis Duport’s legendary Essai from 18062. These methods served as blueprints for most 19th-century cello treatises: a theoretical part, divided into chapters by subject and enriched with technical exercises, was typically followed by a practical section consisting of études in simple forms, each focusing on a specific technical topic.

The limitations of these earlier cello methods become apparent upon closer examination: their language and exercises were too complex to allow students to approach them independently. Furthermore, while they were usually very encyclopaedic in character, they often lacked in clarity and depth. This pedagogical gap explains why Dotzauer felt compelled to create an alternative approach—one that would reach a broader audience through greater clarity and be based on the playing style of Bernhard Romberg, one of the greatest cellists of all time. This last point further emphasises the need for an original cello method written in the German language, something that did not exist at the time. Not only were the first editions of both Duport’s Essai and of the Methode du Conservatoire written exclusively in French—a language young aspiring cellists almost certainly did not master—, but Romberg’s style was so novel compared to that of his French colleagues that an evolutionary step became paramount. In order to reach an even greater audience, though, Dotzauer asked one of his students—Charles Mincke—to translate his book in French and write a preface to it. This introductory text was strongly criticised by the press of the time3, mainly for its orthographical defects and odd style in both languages. It is perhaps unsurprising that Dotzauer might have been concerned of being accused of plagiarism for writing a method that so closely resembled—at least in format—those of the French masters who preceded him. This preface, then, may have served to win readers’ goodwill. The reviewers, though, immediately dismissed these preoccupations, saying that:

[…] It would certainly be unfair, and indeed a complete failure, to hastily conclude from this the value of the work itself4.

The final result, in fact, far exceeded what anyone—possibly Dotzauer included—could have ever expected.

Hunting for the sources

Contrary to what one might expect of a prolific composer with over two hundred works published during his lifetime, Dotzauer’s autographs and fair copies are an absolute rarity. When it comes to the Violoncello–School, Op. 65, however, we are fortunate to have the complete autograph of the text and of the two musical appendixes. All the sources are held at the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek (Bavarian State Library) in Munich, Germany, and have been digitised and made available online in open access5.

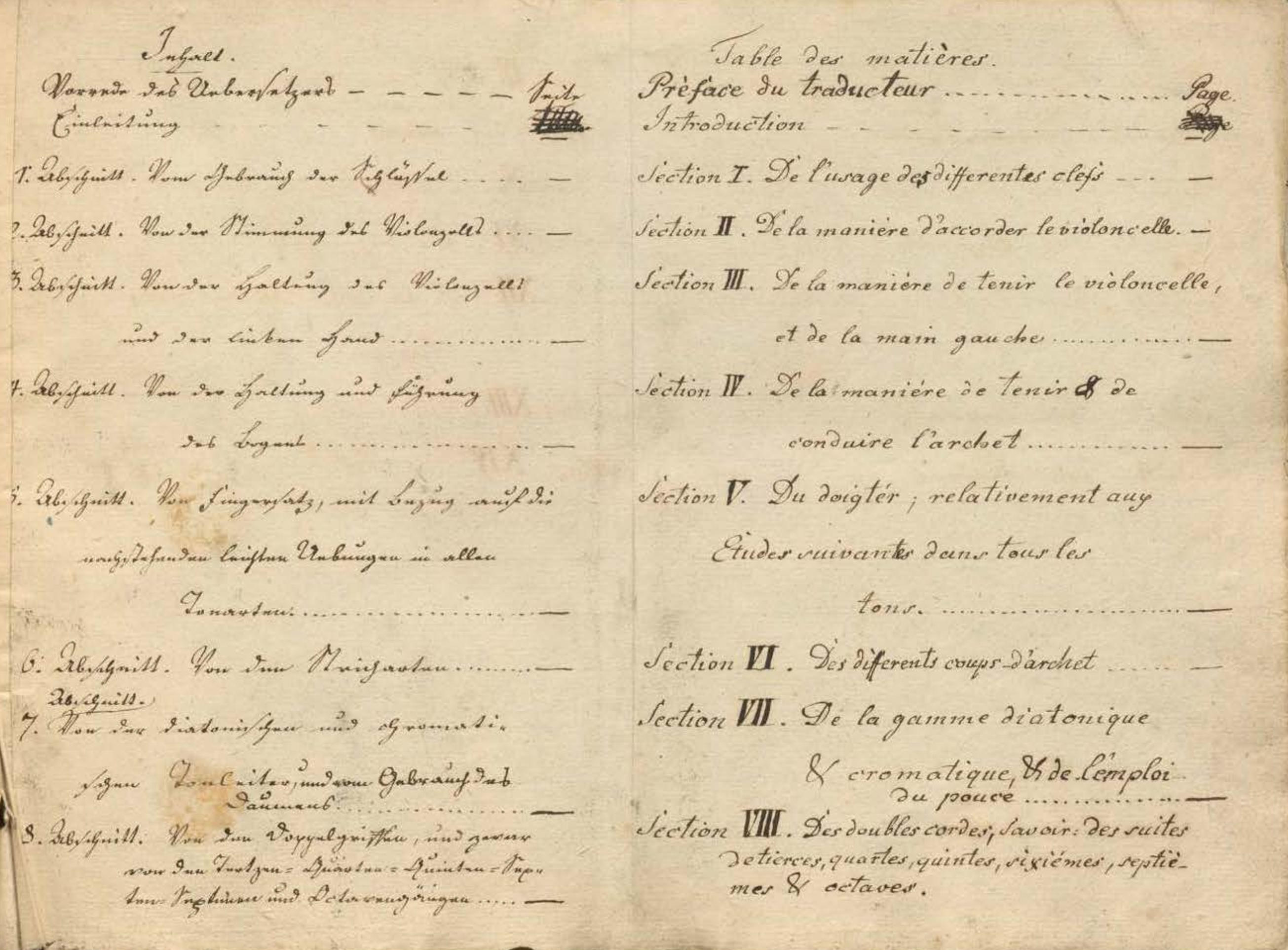

The autograph of the text portion6 bears the title Violoncell-Schule | von | J. J. F. Dotzauer. | Methode de Violoncelle | par | J. J. F. Dotzauer and is composed of 56 folios (leaves) of 32.5 × 24 cm, totalling 112 pages. On the title page, at the bottom centre, there is an old ink signature “2014” representing the publisher number. The manuscript consists of the original German version and a French translation, each written together on one page in two columns. The German text is written in the German Kurrent script, while the French text is in Latin script. Numerous musical examples are embedded in the text, which comprises an introduction, 14 sections, and an appendix.

The manuscript also includes a sheet of paper (35 × 21 cm) of a different paper type and by a different hand with the “Translator’s Preface” (German/French) attached, which, like the main source, is written in two columns. The last page is blank.

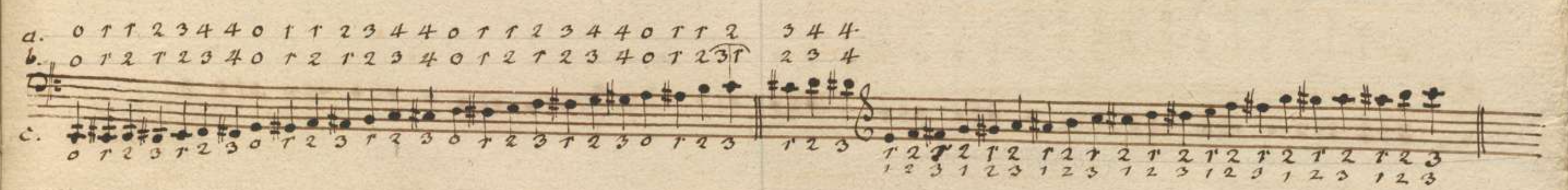

The autograph of the first appendix7, titled Tonleitern und [crossed out: leichte] Uebungen in allen | Dur= und Molltonarten. | Gammes et Leçons dans tous | les tons majeurs et mineurs, is composed of 21 leaves of 33 × 24.5 cm, folded from 10 sheets of music and sewn together with an extra music page with thread. The last page (f. 21 v) contains only empty staves. On the bottom left of the first page (f. 1 r), the library’s signature was added as “Mus.Schott.Ha 1922-4”, evidently in another hand and at a later date from the drafting of the manuscript. On the verso of the same page, a stamp of the library (“BSB”) is visible in the middle bottom of the page, with the shelf-mark “14L.A/463” just below it. The 63 pieces form the first appendix of Dotzauer’s Violoncello-Schule8, as is evident from the printed edition. See, for example, D-Mbs 4 Mus.th. 2211 and, for the second part of the appendix, RISM No. 1001063750. Nos. 1–13 are scale exercises for one cello. From number 14 onwards, there are two-part exercises where a second cello accompanies the main part.

The musical text bears engraver’s markings in red chalk and pencil, indicating the casting-off he planned to realise.

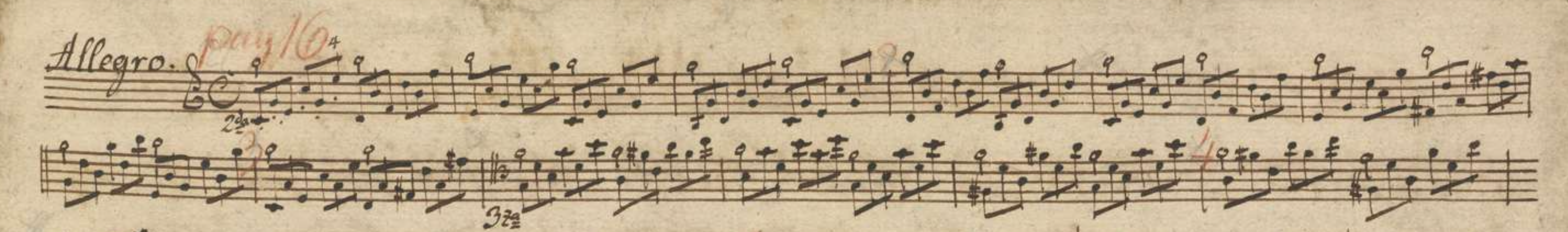

The autograph of the second appendix9, titled Uebungen im Aufsatz des Daumens. Études en employant le pouce, consists of three sheets of music and two music pages, sewn together with thread. The page size is 33 × 24.5 cm, and the musical text contains similar engraver’s markings to those found in the first appendix.

On the bottom left of the first page, we find the library’s signature again as “Mus.Schott.Ha 1922-5”, followed by the stamp and the shelf-mark “14L.A/463” on the verso. These 24 pieces included here form the second appendix of Dotzauer’s Violoncello-Schule: numbers 1–8 are two-part exercises (Tempo di Menuetto with Trio, Andante, Andantino, Allegro, Andante, Cantabile, Andante, Allegro), numbers 9–22 are single-voice bowing exercises, number 23 is an “exercise with the [!] fourth finger in thumb position,” and number 24 is a single-voice Allegro, originally exercise no. 11 from his Op. 54.

The engraver’s markings correspond faithfully to the casting-off of the first printed edition, published by Schott as Méthode de Violoncelle: = Violonzell–Schule, with plate no. 201410. The copy consulted for this publication is stored at the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in Munich, Germany, under shelf-mark 4 Mus.th. 221111.

Publishing outline

The present publishing initiative around Dotzauer’s Violoncello–School will comprise several volumes to facilitate access to each component of this substantial work, thereby honouring the author’s original intent. Here is the outline:

- The main body of the work issued as a standalone electronic publication, and adapted into modern German by Dr. Bernd Krause of Büro für Geschichtswissenschaften12 to make the 1824 text accessible to contemporary readers, and, for the first time, translated into modern English.

- The first musical appendix—this volume, plate no. ASE Editions 0104—containing 63 scales and exercises that do not require the thumb, as a separate publication, in both printed and digital format. The full score will include the original markings found in Dotzauer’s autograph—vastly more accurate than those in the first edition—, while the separate parts will feature editorial fingering and bowing suggestions.

- The second musical appendix, plate no. ASE Editions 0106, containing 24 exercises requiring the thumb, as a separate publication, in both printed and digital format, with the same treatment of score and parts as the first appendix.

- A short volume including only the 24 scales in two octaves and Dotzauer’s proposed rhythmical patterns conveniently listed and ready to be applied to every scale, plate no. ASE 0110.

- A complete edition including the text portion and the two musical appendixes, exclusively in printed format, with plate no. ASE 0092.

The Violoncello School — Op. [65]13

As soon as we start sifting through the pages of Dotzauer’s Violoncello–School, the essential advantages over the preceding methods begin to emerge: a greater clarity, a more accurate understanding and analysis of fundamental topics—such as posture— its systematic ordering, tireless research, and striving for completeness, all concur to the rise of a true masterpiece.

Dotzauer opens his succinct introduction with the assumption that students already possess the requisite elementary knowledge regarding notes, rhythm, clefs, and so forth—something that, today, is regrettably neglected. He does not consider a good teacher superfluous in the instruction of his method, but, at the same time, he wishes to have succeeded in presenting and communicating his principles of cello playing as simply, clearly, and convincingly as possible. Before moving on to the first true section, Dotzauer insists—as though belatedly recalling this essential point—that students should, as soon as possible, master the theory of proper harmony, lest their playing inevitably suffer.

The first section of the book deals exclusively with the usage of clefs, and it is already a breakthrough: besides the bass clef, the tenor and treble clefs (at pitch!) are to be used. This is thanks in no small part to the work of Bernhard Romberg who, in his compositions, did away with the soprano and alto clefs and, most importantly, with the usage of the treble clef transposed one octave down. Now, every clef reads at pitch, a major difference from before.

A second section on tuning the cello is followed by a masterful section on posture, with all rules, advantages, and techniques thoroughly explained and made clear by the two accompanying copperplate illustrations. Fascinatingly, unlike Duport, Dotzauer considered only two positions without thumb support: the first—equal to ours—and the second—our fourth position. While this may be one of the few aspects of Dotzauer’s teaching that did not make it to the present day, the critics of the time were particularly intrigued by such a simplification. Indeed, Friedrich A. Kummer, Dotzauer’s most accomplished student, would, some fifteen years later, classify the four neck positions and the three intermediary positions as we do today. It is likely that Dotzauer himself evolved his thinking in the years following the publication of the school.

The focus given by Dotzauer to the holding and conducting of the bow is unprecedented, with most of his teachings being still valid today. If we look at how Duport and Romberg held the bow, it is evident how Dotzauer’s grasp is on an entirely new level, one that will pave the way for finger flexibility in the generations to come. The greatest merit of Dotzauer’s school when it comes to bow technique goes beyond what is written in the book. It actually inspired an entire generation of cellists to improve, research, and experiment, refining their master’s technique with every iteration.

The fifth section, on fingering, is connected to an appendix of 63 scales and practical exercises, most of which feature accompaniment of a second cello. While they are clearly modelled after Duport’s 21 Exercises, they are vastly simpler and better graduated in difficulty.

The sixth section includes various combinations derived from the three principal bow strokes, and also thoroughly discusses the arpeggio (with 81 variations) and the staccato technique. Dotzauer’s crowning achievement, however, lies in the seventh section, which provides the definition of the best fingerings to be used with the chromatic scale.

The third and sometimes fourth octave of all major and minor diatonic scales are shown here14—the first two octaves appearing in the appendix—alongside instructions for the use of the thumb15. Regrettably, the descending scales lack any fingering suggestions, an inexplicable slip that was already noticed by the reviewers at the time.

Double-stops are covered extensively by Dotzauer in the eighth section, with gracious references to his predecessors’ methods (the Paris Conservatory Method and Duport’s Essai) and to three of his collections of solo studies (Opp. 35, 47, and 54). Comprehensive coverage of ornaments follows in the ninth section, with dedicated musical examples demonstrating how to realise each kind.

Harmonics are the topic of the tenth section, and it is immediately evident how much they captured the author’s interest. Less than fifteen years later, in 1838, Dotzauer’s method on harmonics (Op. 147) would be published, bringing to fruition all his efforts and research. At this stage, though, he did not feel ready to go beyond touch-fourth artificial harmonics.

The next three sections deal with the pizzicato, the resonance of untouched strings, and the rules for accompanying a recitativo, an activity that Dotzauer deemed fundamental for the formation of a professional cellist.

The fourteenth section, then, covers performance, that is, the core motivation that brought Dotzauer to write this book.

The author thoughtfully posits that one can only truly speak of this—the actual soul of playing—when the student has acquired all indispensable preliminary knowledge, has at least learned to overcome the mechanical difficulties, has skilfully mastered the practical part of the art, and has thereby become receptive to the aesthetic16.

For Dotzauer, the key requirements for an accomplished cellist are:

- Purity of intonation

- Regular fingering

- Mastery of the art of bowing

- Coordination of bow and fingers

The final appendix preceding the musical examples describes the cello as an instrument, bestowing precious recommendations on maintenance, strings and rosin choice, and on how to modify the position of bridge and soundpost to achieve the desired sound.

While the goal of this overview of Dotzauer’s Violoncello–School was to provide an introduction to a truly remarkable work, we believe it was crucial to both clarify the outline of the work and to show how, shortly after its publication, it was met with considerable success. We know for certain that every future pedagogical work written by Dotzauer (and others) would be compared to its “excellent cello method”17, establishing it as a lasting milestone in the firmament of cello literature.

Bottom Line

That’s all for today.

Thank you for reading so far.

Come back next week for the second part, dedicated specifically to the first appendix and its 63 Scales and Exercises for Cello. Subscribe to the blog to be notified of new articles.

Contact me for any questions you may have concerning this edition, either here in the comments or via the contact form on the blog site.

- Pierre Baillot, Jean-Henri Levasseur, Charles-Simon Catel, Charles Nicolas Baudiot, Méthode de Violoncelle, engraved by Le Roy, published and printed by the ‘imprimerie du Conservatoire’ in 1804. Later reprinted by Janet & Cotelle and by A. Kühnel. ↩

- Jean-Louis Duport, Essai sur le doigté du violoncelle, et sur la conduite de l’archet, first published by Imbault around 1805-06, plate number 296. ↩

- Ign[az] v. Seyfried in: Caecilia, vol. 3, Nr. 12, 1825, p. 249-262, dated ‘Wien, im März 1825’ ↩

- Ibidem. ↩

- Record of the work in Stichbuch 4 of the publisher B. Schott’s Söhne, Mainz, with the signature: Munich, Bavarian State Library — Ana 800.C.I.4: https://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb00109531-9

D-Mbs, Mus.Schott.Ha 1922-4, 30000882 ↩ - Available digitally online here: https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/view/bsb00122689?page=%2C1 ↩

- Available digitally online here: https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/view/bsb00122690?page=%2C1 ↩

- RISM No. 1001063694. ↩

- Available digitally online here: https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/view/bsb00122691?page=%2C1 ↩

- At a certain point (p 29) the plate number erroneously changes into 2114 and stays wrong until the very end. ↩

- A digital copy is available here: https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/view/bsb11190934?page=122%2C123 ↩

- Extended link for the printed edition: http://www.geschichtswissenschaften.com/. Accessed July 2, 2025. ↩

- While this opus number was mentioned in a letter to the publisher Schott in 1824, it was never printed on the cover of any reprint. ↩

- With the cello’s fingerboard being about a minor third shorter than it is today, most scales stopped after the third octave. ↩

- The symbol for the thumb (a circle with a trait centred below it) makes its debut here, while Duport was using a simple circle for it (and lowercase letters for open strings!). ↩

- Ignaz v. Seyfried, in: Caecilia, vol. 3, Nr. 12, 1825, p. 249-262. ↩

- Collective review of op. 65 and 126 together with a work by Joseph Merk and Dotzauer’s „6 Rondinos“, without author, signed „d. Rd.“ = „die Redaktion“, in: Caecilia, vol. 17, Nr. 65, 1835, p. 51-56 ↩

3 thoughts on “Dotzauer Project — Episode 14”