A deep dive into the Scales and Exercises, Appendix 1 of the Violoncello School, [Op. 65] — Chapter 2 (Ex. 23-44)

This article is the second chapter of the follow up to the Editorial Notes that can be found in the published edition and available here. The first chapter, covering exercises 1 to 22, can be found here. The book is available in print (coming Fall 2025) as well as digitally (PayPal/Stripe — Apple Pay/Credit card). Five promotional videos have been released for this edition and they can be watched here (No 22, No 26, No 28, No 30, No 47). You can also expect several videos from me explaining these exercises in great detail.

D major

There is nothing special worth mentioning in this scale, which is possibly the most comfortable and rich in resonance on the cello. Two fingering sets are proposed, one with and one without open strings. The alternative fingering is added only during the ascent and should be assumed to stay the same during the descent.

Exercise 23

Sixteenth-notes make their debut in this scale-based exercise in 6/8 time. The opening four bars present big intervallic jumps followed by long descending scales, while the next four bars check whether the student has carefully practised Ex. 1-13. The final phrase alternates ascending and descending scales.

It would be useful to practise this exercise in legato, half-a-bar per stroke, not too slowly but always using the whole bow. Dotzauer’s original fingerings assume the exclusive usage of the first and fourth positions. The additional suggestions in the separate part provide an alternative approach.

Exercise 24

A scale-inspired exercise, No. 24 offers a new practicing idea that should be applied to all scales: start on note 1, play notes 2-3, repeat note 1 and iterate likewise from the following note (e.g., D-E-F-D, E-F-G-E, etc.). It is paramount that this exercise be practised with four-notes legato, first with the entire bow, and then with each half of the bow. The accompaniment begins with a chromatic descent, and finishes with a point-counter-point line in the last four bars.

Dotzauer’s original fingerings could be used to practise string changes, but, ultimately, the alternative proposed in the separate part appeared musically and technically more solid to me.

B minor

This scale is interesting because Dotzauer suggests a different fingering for the descent compared to the ascent. As soon as we get to the top, in 6th position, the G-natural of the return is marked with a 4th finger, in 4th position. This provides a great advantage for intonation, but we also recommend practising this with the backward-extended 1st finger, as marked by the italicised digits.

Exercise 25

A fully syncopated exercise, this duet explores both the half and the advanced-1st position (bb 6-7, 10), alongside quick bow strokes at the extremes of the bow (bb 8-11). Its 11-bar length makes its irregular form musically challenging to internalise.

Once again, Dotzauer doesn’t mark the recommended starting bow direction. Starting down-bow is more useful to practice the weight in the last third of the bow, while starting up-bow is simpler overall.

Exercise 26

At 56 bars of length, this 6/8 duet is the first massive exercise of the series. It is also one of my favourite duets of this collection, if not the favourite. While one should begin by practising it slowly and also in legato by half-a-bar, this exercise becomes truly effective at a faster tempo, proving to be both extremely challenging and superbly enjoyable. The first part (bb 1-16) focuses entirely on the advanced-1st position, a fermata allowing for a good page turn in the score as well. The second part (bb 17-32) modulates to D major, radiating optimism throughout. The opening bars make a comeback, marking this as the first piece with an intelligible major form (A-B-A, or song form). The reprise is, though, quickly cut short by a Neapolitan chord (b 45), a diminished seventh of the Dominant (b 46), and a perfect cadence to welcome a final period of I-V buoyant alternation.

This is certainly not an easy piece, but it is one from which students can learn immensely. To this end, I suggest a proposed target speed of q. = 104. Here, for the first time, I have marked the places where a finger on two strings should be placed (see later in the Performance Instructions and Notation section).

A major

We continue our ascending sharps progression with A major. Once again, there are two sets of fingering and no additional marking on the returning path. The last G-sharp is played with the 2nd finger in 5th position during the ascent and with the 4th finger in extended-4th position when coming back. I propose trying to keep the same fingering in both directions as well.

Exercise 27

This duet focuses on the dotted-8th-note plus 16th-note rhythm (also known as “French rhythm”) and is a plain harmonisation of the underlying scale. Students should be made aware of the chords implied by the melodic line.

Additional practice ideas include: legato by two, with or without a staccato dot on the shorter note; legato by half-a-bar, and by a whole-bar. Finally, the long-short rhythm should be inverted by placing the 16th-note first. The separate part marks wherever the second disposition of the left hand should be kept.

Exercise 28

Like No. 17, this exercise focuses on developing a deep and beautiful tone, with long slurs requiring exploitation of the entire length of the bow. The accompaniment, also melodic in nature, encourages the student to practice the lower line after mastering the top one.

In a few places (bb 7-8, 9-10, 19-20) of the separate part, I have suggested a more frequent usage of the second string.

F-sharp minor

This scale does not offer a 1st-position starting option, opting instead for the upper-3rd position from the outset. The only alternative fingerings are proposed when avoiding the open A string (during the ascent) and the open A- and D-strings (during the descent) is necessary. Once again, Dotzauer is very parsimonious in fingering suggestions in the descending path, something that our italic digits hope to remedy.

Exercise 29

The ascending scale of this duet in 2/4 time covers the first octave in half-notes, the second in quarter-notes, and the whole descent in eighth-notes. The top voice, instead, accompanies it with upbeat patterns. It is fundamental to avoid stiffening the right arm during rests. Do not abruptly stop the bow; instead, make it weightless by thinking of it as a feather gliding on the string.

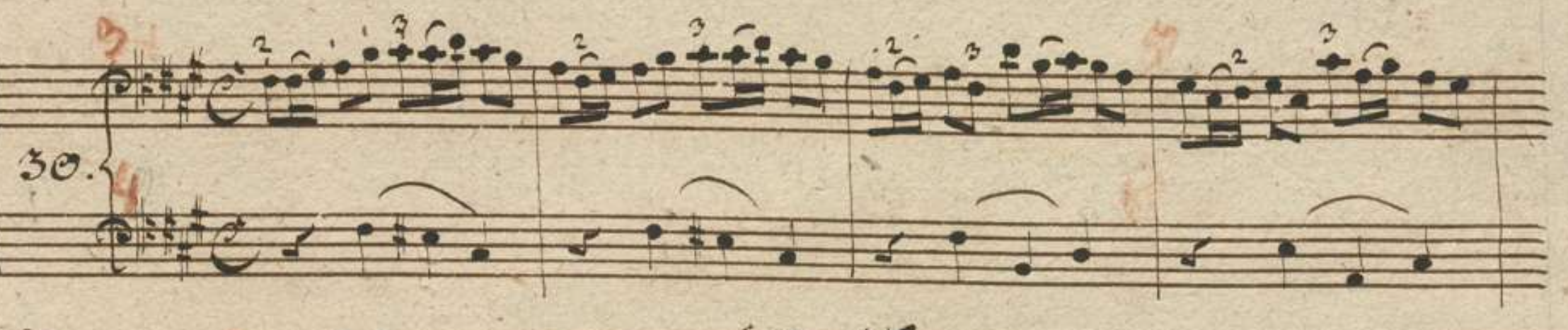

Exercise 30

This longer exercise in common time focuses on the rhythm proposed by the first bar, in a song-like form, with the middle part in the relative key of A major.

The entire duet should be played in the middle third of the bow, paying attention to sound definition, as the short notes may lure students into the trap of playing them too softly.

E major

As the sharps continue to increase, it makes less and less sense to even propose a variant with open strings, but Dotzauer keeps trying, suggesting a quite awkward fingering as its first choice. The second set of fingerings, using the so-called Universal Fingering (three notes per position), is much better and also avoids the strange position change on the second note of the descent. This alternative, though, is not written out in the coming back, prompting students to exercise their memory.

Exercise 31

This brief exercise presents a complex rhythmical structure in its foundation scale, with the main voice emerging through contrary motion. By this point, great confidence in the first three positions should have become a given. Do not forget to practice this melody in half-a-bar legato patterns. In any case, this exercise should not be played too fast (no more than e = 80).

Exercise 32

In complete contrast with the previous exercise, No. 32 offers a simple song form (A-B-A), focusing on a specific rhythmical pattern: five detached notes followed by three slurred ones.

This requires careful planning of bow management, with the fifth note being the one requiring the most bow and the lightest one at the same time. The whole piece should be practised in the middle third of the bow, and particular attention should be given to bb 7 and 28, where the slurring pattern changes to 1 + 7.

An overprinting issue in the first edition makes the initial time signature (c) look as if it were an interwoven double-c, which in certain editions used to mean “cut-C” (cutC). Fortunately, the manuscript is very clear.

C-sharp minor

We finally leave open strings behind with this scale, where at least the ascent has only one proposed set of fingerings. For the descent, Dotzauer proposes a switch from half to first position for the first three notes. This is something that can be practised out of curiosity, but that doesn’t bring any particular advantage over the second option written above.

Exercise 33

This duet is a beautiful example of one of the most basic—and yet most effective—techniques of counterpoint: contrary motion. Double-sharps also make their first appearance here.

Exercise 34

A companion to Nos. 17 and 28, this exercise focuses on looking for a beautiful, round tone in an apparently simple melody. The accompaniment begins one bar later, but immediately engages in a counter-chant that has the goal of teaching the student how to recognise a prominent melody. In this way, they will learn when to emerge and when to leave room for their partner.

In the separate part, I suggest starting from the second position on the D string, something that Dotzauer probably took for granted without specifying it. I suggest a target speed of q = 96–108 in order to gain the maximum from practicing this piece.

B major

For the first time, we only have a single set of proposed fingerings, going from 2nd to 6th position. Since Dotzauer doesn’t cover enharmonic keys, this scale should also be practised as C-flat major.

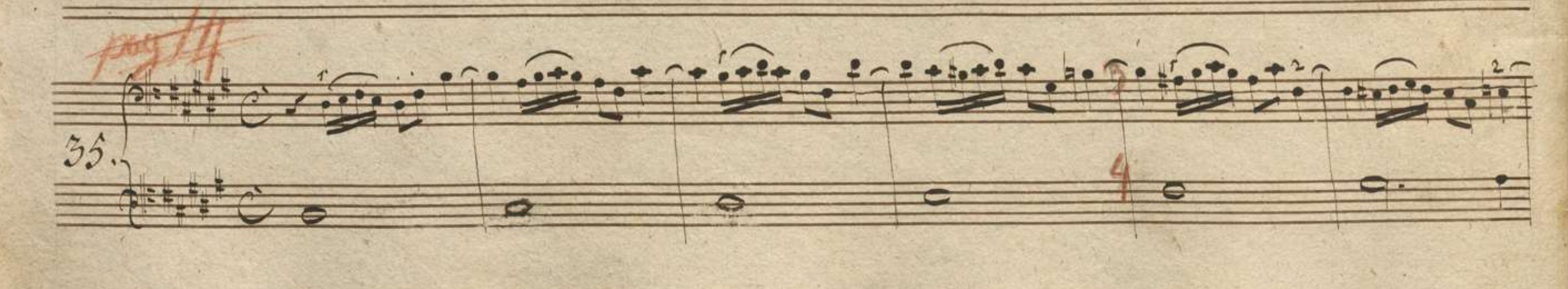

Exercise 35

The scale foundations of this exercise go back to long notes, with the melody above it almost improvising over a constant rhythmical pattern.

In b 10, an A natural is assumed to have been forgotten (or taken for granted) by Dotzauer. The rules for accidentals’ duration were not so strict in the 1820s as they are today, but very few players would have ever had any doubt on what correct note to play here.

There is a single tricky passage in b 13 for which I have provided a fingering suggestion that I think Dotzauer should have added himself.

Exercise 36

This exercise has a beautiful syncopated melody in the second cello, while the first one accompanies it with finger-twisting patterns based on the B-major scale. After the notes have been secured by the left hand, one should not fall into the trap of playing this too slowly. Once again, the proposed pattern should be practised in all other scales.

G-sharp minor

There is nothing special to mention in this scale, which, having only a single clear possible fingering, is quite straightforward. Do not forget to also practice it as A-flat minor.

Exercise 37

This exercise is a crucial one because it silently introduces something that Dotzauer does not cover in the text portion of the book. Modern players may be familiar with the ‘×’ character signifying an extension between two fingers of the left hand, usually fingers 1 and 2. While I have not been able to pinpoint the exact moment in cello history when this became mainstream, it certainly was not so in Dotzauer’s time. Exercise 37, built on a constant rhythmical pattern over the G-sharp minor scale, adds a horizontal line under the notes that are to be played in extended position.

I believe this to be an incredibly helpful and original notation, and something that—ever since having discovered it—I have adopted in both my teaching and personal practice. At the same time, I do not think it should substitute the ‘×’ character, which only refers to extending the space between any two given fingers. Rather, it should complement it.

In the separate parts, I have adopted this practice from No. 6 of this Appendix, and explained my choice in a footnote.

Exercise 38

This duet has the form of a miniature fantasy: it starts as a melody with accompaniment (bb 1-4), it continues with a canonical portion (bb 5-16), and it concludes again with a shortened version of the initial melody. 32nd-notes make their debut here.

F-sharp major

A very straightforward scale, this should also be practised as G-flat major.

Exercise 39

This scale-based exercise focuses on syncopes, with the foundation scale proceeding in quarter-notes and the main line “hiccuping” an 8th-note out of phase. Of particular interest is b 7, where the syncopation becomes increasingly subdivided with the diminution of the rhythm.

Exercise 40

This exercise in 3/4 time has an A-B-A songlike form, with both the outer parts being imitative in nature. This duet should be played with as much bow as possible, and the student should also practise the lower part once the main one has been mastered.

D-sharp minor

In this scale, Dotzauer proposes the open string as his first choice for the C-double sharp, but gives the 4th-position alternative above. This should also be practised as E-flat minor.

Exercise 41

This scale-based duet has a couple of peculiarities: the foundation scale is only ascending while the main part does not have a single note starting on the downbeat until the very last bar, the focus being upbeat notes that extend into the following bars. Emphasis marks decorate these upbeats throughout the piece.

From b 8 until the end, there are no more slurs over the two 16th-notes. In terms of bowing, the exercise works in both ways, and it should be practised in either version.

Exercise 42

The longest exercise in the collection is also the only one in cut-C time.

The entire main part is made up of arpeggios (broken chords), while the second cello plays a very low and dark line. This is perhaps the most technically demanding duet of the first Appendix, mainly for the complex key and for the often awkward hand positions required.

While this should be practised slowly and with the whole bow at first, the final concert version should be played quite fast (I suggest around h = 144) and in the middle third of the bow.

Understanding when to use the second disposition of the left hand and when to simply stretch the fingers is crucial, which is why I clearly marked every occurrence in the separate part.

F major

With all sharp keys exhausted, we can now move forward to flat keys, starting with F major. It is clear, now more than ever, that the order chosen by Dotzauer follows a circle-of-fifths logic and not a difficulty progression. If we exclude the first exercises in C and G major—which are quite simple—a teacher should feel free to jump around this book to pick the exercises they think are most suitable to their students’ needs.

For this specific scale, two fingering sets are proposed, one with and one without open strings, exclusively during the ascent.

Exercise 43

This duet’s main part is based on a simple rhythmical pattern: four eighth-notes, four sixteenths, and two eighths again, with the first and last eighth often being replaced by rests of equivalent duration. The underlying scale, instead, is a regular succession of half-notes.

While one could decide to begin each bar that starts with a rest with an up-bow, I suggest starting up-bow in b 1 and then letting the bow flow naturally following the patterns written by Dotzauer. This approach will prove logical.

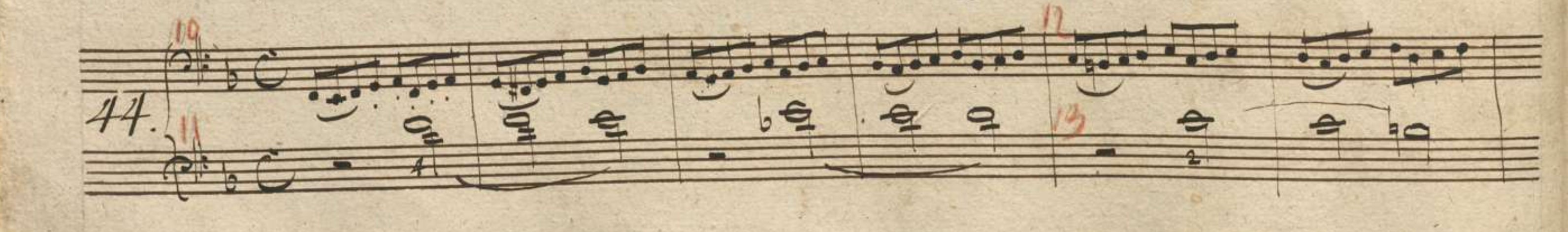

Exercise 44

Leveraging the power of contrary motion once again, this duet proposes a pattern that could (and should) be applied to other scales. Each bar begins on a new note of the F major scale, touching a lower neighbouring tone (e.g., F-E-F), then repeating a three-note ascending fragment based on the main note twice:

The accompaniment descends chromatically for one octave, veering then towards a more standardised bass accompaniment towards the end. A minimum practice speed of q = 104 is suggested once the left hand is no longer an issue.

Bottom Line

That’s all for today, folks! Thank you for reading so far.

Come back next week for the third and final chapter of this deep dive, covering exercises 45 to 63. Subscribe to the blog to be notified of new articles and consider leaving a like if you enjoyed reading this one.

Contact me for any questions you may have concerning this edition, either here in the comments or via the contact form on the blog site.

Until next time, thank you!

One thought on “Dotzauer Project — Episode 14”