A deep dive into the Scales and Exercises, Appendix 1 of the Violoncello School, [Op. 65] — Chapter 3 (Ex. 45-63)

This article is the third chapter of the follow up to the Editorial Notes that can be found in the published edition and available here. The first and second chapters, covering exercises 1 to 22 and 23 to 44, can be found here and here. The book is available in print (coming Fall 2025) as well as digitally (PayPal/Stripe — Apple Pay/Credit card). Five promotional videos have been released for this edition and they can be watched here (No 22, No 26, No 28, No 30, No 47). You can also expect several videos from me explaining these exercises in great detail.

D minor

This scale required the implementation of three suggested fingerings in the descending portion because the only digit added by Dotzauer (on the last A) was of no great help without preceding specifications. This is one of the great risks of being an incredibly gifted artist and of coming to the cello with an already formed familiarity with string instruments. Even if you place the goodwill of wanting to teach something, you always miss some basic details, taking them for granted because you didn’t have to struggle with them yourself.

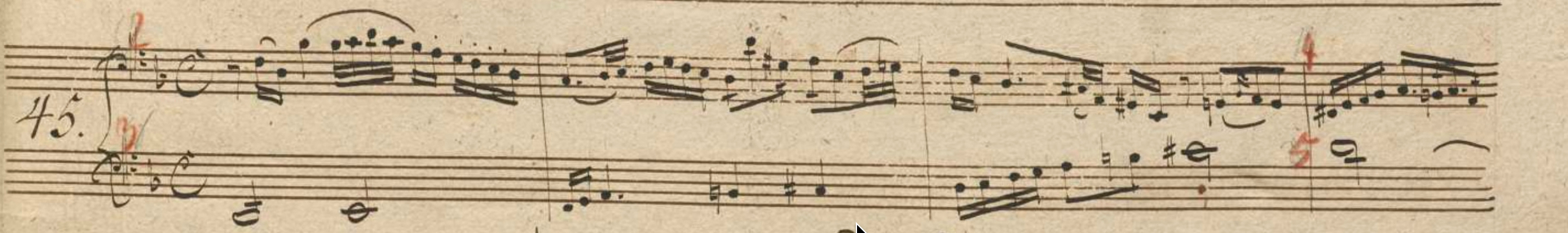

Exercise 45

Triplets of 32nd-notes make a debut here, in what I consider the most interesting duet of the entire collection. The supporting skeleton of the piece is the D minor scale, proposed in such a complex rhythm to make us assume that Dotzauer went over several iterations before finding the proper balance between the two lines. The first cello’s rhythm is hyper-complex too, with ties, dotted notes, both simple and compound syncopes, triplets, and more.

It should be practised—and played—fairly slowly (I suggest a metronome marking of q = 40). An additional notable detail is the Picardy ending in D major. A few courtesy bowing marks have been added in the separate part.

Exercise 46

Possibly realising what he had just done with No. 45, Dotzauer proposes another scale-based exercise, this time with a trivial rhythm for the scale—just half- and whole-notes. The main line, instead, introduces 8th-note triplets for the first time—No. 26 was in 6/8, so those note groups do not technically qualify as tuplets. The first period alternates scale fragments to arpeggios in detached notes, while the second adds slurs to the mix. For the left hand at least, this is a much harder piece than it may seem at first sight. It is paramount that the student practices this in legato by three notes throughout until the left hand is completely automated.

Exercise 47

Finally, with No. 47, we get a major contrapuntal duet in this exercise in 6/8 time. The main line begins, imitated one bar later, a perfect fourth below. The two lines proceed teasing and imitating each other, bringing the first period to a close in B-flat major. A modulating bridge touches G minor, F major, and C major, before coming back to D minor. The initial melody comes back in b 21, with a colourful coda closing the piece on a dramatic tone.

This kind of piece is very useful to prepare for the Gigue from J. S. Bach’s First or Third Suite, and also to make students become familiar with contrapuntal forms. Having such a simply structured two-voice invention allows them to be prepared for when bigger forms, such as fugues, will come by.

One drawback of this piece in its original form is the total lack of bowing suggestions from Dotzauer; it was challenging to devise a truly functional solution, and I hope my proposal in the parts will help you solve the bowing riddle.

B-flat major

While Dotzauer proposes an alternative fingering for the ascent, he doesn’t repeat it for the descent, something that I have already remedied in the score by means of italicised digits.

Exercise 48

Fresh from the inspiration of No. 47, Dotzauer builds this scale-based duet around imitation, the main cello apparently starting with the B-flat major scale itself, with the accompaniment taking over from the second half of the first bar. This exercise should not be played too fast, and great care should be given to bow management. The first two bars should use as much bow as possible, while bb 4–6 should stay in the middle third of the bow. Bars 6 & 8 focus on string crossings, where students should look for a continuous movement of the wrist and forearm. Finally, bar 7 should use a very light and long stroke on the first note, and control the up-bow so that bar 8 begins at the barycentre of the bow.

Earlier, I recommended not to play this too fast; I should add, though, that playing it too slowly is also not ideal either because it will make b 7 impossible to play effectively.

Exercise 49

This duet’s form could be classified as a ricercare, or a prélude form, its focus being exclusively the exploration of the keys around B-flat major using a virtuoso, fast, and technical artifice. The main line plays exclusively 16th-notes in a 1+3 bowing pattern that requires the usage of the upper half (if not the upper third) of the bow. This practice being quite taxing for the right arm, I recommend studying this exercise slurred by four notes, initially with the whole bow. Once the left hand is no longer a distraction, one can start accelerating, eventually applying the correct division of the bow.

The repeat mark in bb 22-3 was almost certainly placed there to save ink, paper, and time, but since removing it did not improve the casting-off, we decided to keep it. The final, concert version should be played as fast as possible without sacrificing clarity.

G minor

Once again, Dotzauer only places a single suggested fingering during the entire descent of this scale, requiring careful additions to avoid misunderstandings.

Exercise 50

The G minor scale in the lower voice of this duet in 3/8 time covers the full ascent with the same rhythm: dotted 8th-note and three 16ths. This forces the main voice to adapt, using long notes and suspended intervals. In the next four bars, the first cello imitates the rhythm proposed by the scale with three slurred 16th-notes followed by three detached ones. The final four bars, instead, focus on large intervallic jumps and syncopes. It is a short exercise, but one from which students can learn a lot.

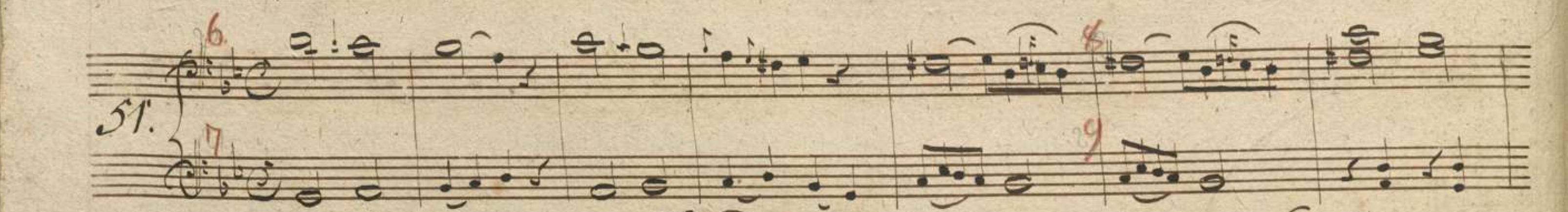

Exercise 51

This duet in common time introduces ornaments, with two of the most common forms: appoggiaturas and acciaccaturas. In this case, consulting the manuscript was fundamental because the engraver of the first edition not only copied several notes wrong, but also deliberately exchanged one kind of grace note with the other.

The piece is divided into three main parts: the first (bb 1-8) is melody-focused, with both parts singing as in a vocal duet. The second (bb 9-16), instead, is contrapuntal in nature, with four bars of imitation and four of accompanied melody. The final part (bb 17-24) goes through a couple of harmonic progressions to reach the desired key before offering a dramatic ascent followed by a scale down to the tonic, and a final, ornament-rich cadence.

E-flat major

Two fingering sets are proposed for this scale, but only for the ascent. The missing helpful fingerings for the descent have been added in italic typeface.

Exercise 52

We continue our exploration of ornaments with this duet in common time: turns, with or without additional accidentals, and mordents, both inverted, standard, and of different lengths, significantly increase the level of proposed difficulty. The text part of the book explains how to realise these ornaments in extraordinary detail, but, for those who do not own that version of the book, I have added Ossia staves in the separate part.

Once again, the manuscript and the first edition differ here: the type of turn used in the first edition is different (and unusual even for modern standards), and, in one occasion, a vertical slash is added to indicate an inverted turn where the manuscript shows no trace of it.

Exercise 53

This duet, the only one in 3/2 time, could be subtitled “the stamina exercise”. It is quite long and features a mordent on the third note of each beat. This may not appear to be a problem in the beginning, but, as one progresses through the piece, finger articulations will begin to get tired. One should not try to practise this in its entirety on the first attempt. Build your stamina over time. Furthermore, familiarising oneself with the notes without ornaments could be an excellent start.

C minor

The C minor melodic scale is offered with two sets of fingerings and should be practised alongside its major parallel to make students familiarise with the different dispositions of the fingers while using the same positions.

Exercise 54

In an unexpected return to more accessible material, Dotzauer writes the first duet in C minor as a simple succession of 8th-notes, with the clear aim of practising regularity. Several rhythmical combinations are proposed.

Exercise 55

This second duet of the C minor group focuses on trills and their resolutions. The first two phrases alternate two bars of trills in unison and forte dynamic with two bars of a dolce melody accompanied by delicate chords. The following phrase integrates upbeat notes to the trills as well, while the second cello definitely embraces an accompaniment role. The ending, in unison and dotted rhythm, restores the epic mood of the beginning.

Trills should be practised with few repetitions at first, lifting the finger high in the air and letting it fall through gravity. Until a concert version can be achieved, it should be possible to almost precisely write the rhythm played by the trill.

A-flat major

As the first scale of the flat portion of the circle of fifths without open strings, A-flat major has only one proposed fingering, the universal one.

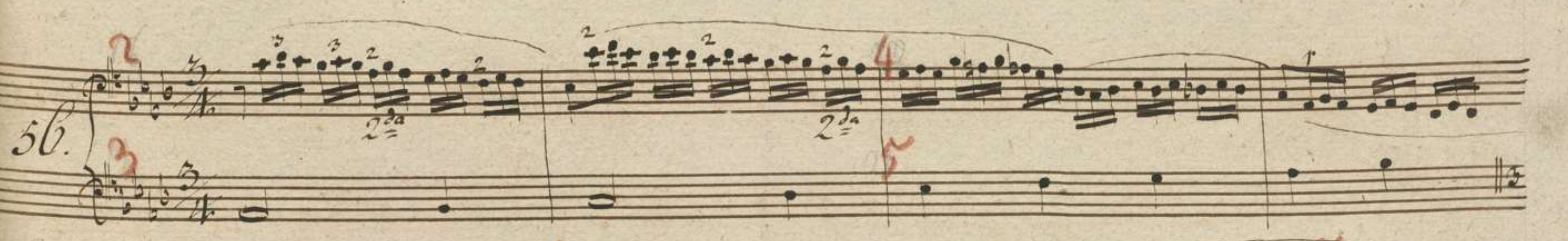

Exercise 56

This duet in 3/4 time focuses on 16th-note triplets whose melodic shape resembles that of a mordent.

It is an extremely challenging exercise, and for two reasons: it cannot be played too slowly, or this will make it too challenging for the bow, nor too fast, as this will make it unmanageable for the left hand, at least for an ordinary student.

Each triplet should be practised independently and repeated several times before moving to the next one, the goal being to get the hand used to the correct movement. Slowly, then, two triplets should be joined together in the same bow, then three, four, and so on until one can forget about the left hand and focus on bow management.

Exercise 57

A moment of respite after No. 56, this exercise focuses on long notes with the whole bow, short grace notes at the point (either in the old or in the new bow, Dotzauer does not specify), two quavers, and a long note to close the phrase. The accompaniment constantly plays a quarter rest followed by three quarter-notes. Bar 7 clearly contains a mistake in the second cello, a missing natural accidental for the D2, which we added in square brackets.

F minor

We are reaching the final stages of this journey, allowing (and encouraging) students to compare scales beginning on the same pitch but constructed in different modes. We have by now learned that Dotzauer was quite sparing with fingerings in the descent, something that we took care to compensate.

Exercise 58

This scale-based exercise is a lesson in scale harmonisation: each bar builds a different chord, although using the same rhythm throughout.

The final four bars also add syncopated patterns to the mix. It is an extremely useful exercise, with the clear aim of building harmonic awareness in the student. This portion of the Appendix, in fact, could be connected with the chapter on accompanying the recitativo, something that Dotzauer considered a key skill for every cellist.

As far as the original bowings are concerned, this piece would end up-bow. One should feel free to change some of the bowing marks in the previous bars if ending down-bow is paramount to you. At the time of Dotzauer, though, ending a piece up-bow was not considered problematic.

Exercise 59

After waiting throughout the entire collection, we finally encounter a full-fledged fugue for two cellos. The most plausible reason why we only have one proper fugue in this book is that a fugue requires a certain amount of space to fully develop all its sections. The shorter exercises we have had in the first two thirds of this Appendix did not meet the basic requirements for complete fugues. The subject is three-bars long and is answered at the canonical perfect fifth above. Already in b 10, we have a new statement of the subject a minor third above (in A-flat major), with the second cello answering at the unison (octave below), but with a delay of just two bars. The next phrase is introduced by the lower line, in E-flat major, with the answer in the upper octave coming two bars later. In b 29, the stretti section begins, with a quick Dominant-Tonic succession in F minor, followed by a serrated alternation of the entrances just one bar apart from each other. The tragic end comes in the last phrase (bb 43ff.) with four F minor chords, preceded by a surprising V/IV – IV – V chordal progression.

D-flat major

The last major scale of the collection should also be performed as C-sharp major and compared to the D major one, to nurture the student’s awareness of the universal fingering system.

Exercise 60

Inspired by the previous fugue, Dotzauer proposes this scale-based duet with the scale starting two-and-a-half bars earlier. The 16th-note quadruplet pattern is practised as an upbeat (bb 3-4, 9-11, 18) and as a downbeat (bb 15-17), with plenty of syncopated rhythms providing the necessary adhesive to the global structure.

Exercise 61

This long exercise focuses on string crossings and on intervals of a sixth. Intonation should be practised in double-stops and in legato, repeating the same dyad twice, one to listen to it first and another to work on the transition between the two. Fingers should be generously lifted in the air to develop the correct articulation. A further practice idea would be to shift the slur forward by one note, thus connecting notes 2-3, 4-5, etc.

The second cello is limited to a support role through a straightforward bass line.

B-flat minor

We have finally reached the last scale with B-flat minor. Once again, this scale should be practised with both proposed fingerings, next to its major sister, and as A# minor.

Exercise 62

This last scale-based duet encourages the practice of trills and their resolutions (bb 1, 4-7) alongside dotted notes (bb 3-8). The bowing shown in the full score is the one found on the autograph copy, while the Ossia stave in the separate part shows an alternative from the first edition. Both solutions work, with the original one being slightly more complex to realise.

Exercise 63

Appendix 1 ends with a long exercise in triplets, useful to practise a continuous alternation between closed and extended disposition of the left hand, especially in the intermediary positions. This is the only duet with a key signature change in the middle, from the home key of B-flat minor to the remote key of A minor. It is also an exercise in stamina, as the left hand fingers are most likely to become tired and experience diminished flexibility until sufficient practice has been completed.

Performance Instructions and Notation

The original notation by Dotzauer has been preserved everywhere possible. Considering the scarcity of fingerings from the author, suggestions have been added in italic typeface where deemed necessary and helpful. Every other fingering is to be considered original from Dotzauer.

The following custom symbol has been added above certain fingering digits to specify that the finger should be laid flat on two adjacent strings to cover the interval of a perfect 5th.

A fingering digit followed by an exclamation mark (e.g., 3!) signals that said finger should go back to its natural position (e.g., an extended second finger coming back to closed position).

An uppercase letter A next to a fingering digit (e.g., 4A) marks the warning that such finger is a half-step higher than where one would expect it to be in its current position. This helps prepare the extended position without needlessly stretching the 1st finger in advance.

Two equal fingering digits joined by a straight line (e.g., 4–4) imply that such finger should slide between the two notes, without being lifted. This technique should be executed without producing a perceptible glissando.

Dotzauer employs a horizontal line to indicate passages to be played in the second disposition of the left hand (extended position). In the original text, the first piece to show this annotation is N° 37. In the edited version of the separate parts, we extended its usage to all previous pieces as well, starting with No. 6. Whenever a single extension was needed, the standard ‘×’ character has been used.

Suggested or implied bowings have been added either through down- and up-bow glyphs or through slurs, exclusively in the separate part. Dotzauer did not repeat equal slurring patterns, nor did he reinstate a previous annotation when he considered it obvious. We have added dashed slurs whenever an omission could have led to confusion and the marking “[sim.]”—as in simile—when the repetition of the previous pattern was unequivocal.

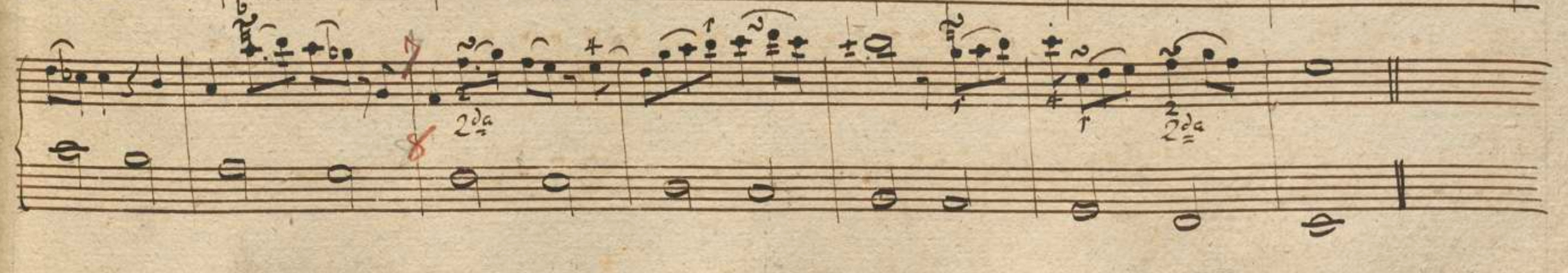

String markings have all been updated to the modern practice of employing Roman numerals (I, II, III, IV), instead of the “1ma”, “2da”, “3za”, “4ta” used by Dotzauer in the first edition.

For bow divisions, I have chosen the German system, where ‘G’ suggests using the whole bow, ‘OH’ its upper half, ‘UH’ its lower half, ‘Fr’ the lower third, ‘M’ the middle third, and ‘Sp’ the upper third. When recommending using the lower or upper two thirds of the bow, I have used a fraction with either “1•2” or “2•3” as the numerator and “3” as the denominator.

Bottom Line

That’s all, folks! Thank you for reading so far.

It was a long journey but we managed to complete it. The next task will be on the 24 exercises and duets in thumb position, so stay tuned for that later in the Fall. I hope you enjoyed reading through this and that you will want to share this with your colleagues and peers. Feel free to leave a comment below, a like, and to subscribe to the blog to be sure not to miss any new release.

Contact me for any questions you may have, either here in the comments or via the contact form on the blog site.

Until next time, thank you!