announcing the Six Lieder for Voice and Guitar, op. 18

This article is an expanded version of the Editorial Notes that can be found in the published edition, available at this link. A promotional video of this score can be watched here.

EDITORIAL NOTES

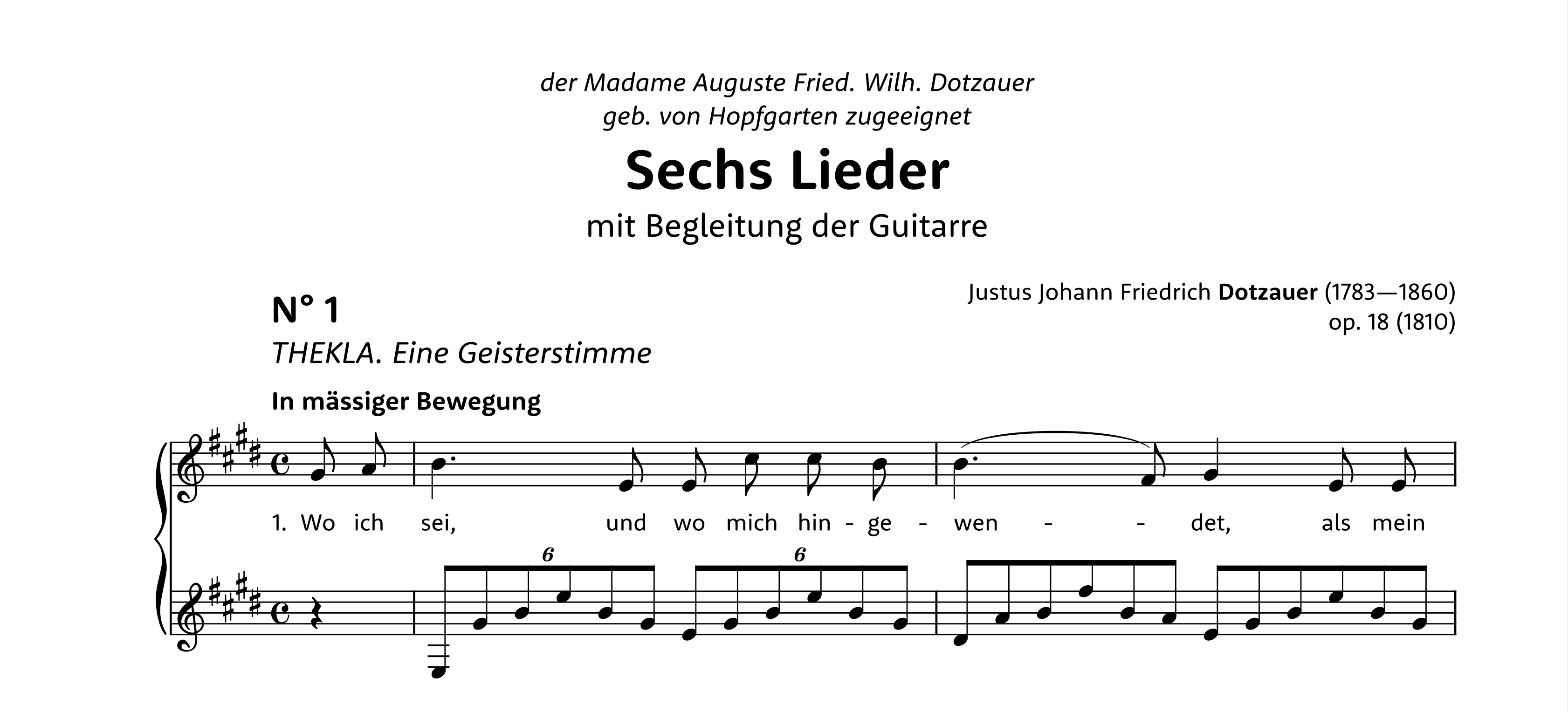

The vocal music by Justus Johann Friedrich Dotzauer (1783—1860) is rare, but so is its beauty. The first edition of this new series in the Dotzauer Project—which we could label Phase 3—starts to delve into his production involving the voice, with a collection of Six Songs (Sechs Lieder), Op. 18, with guitar accompaniment.

Dotzauer and the guitar

If we look at Dotzauer’s production from afar, we can identify several periods in his life when he focused on other instruments than the cello. The bassoon is often present up to Op. 40; the flute gets a Concerto, a Sonata with piano, and three Quartets with strings; the French horn—being it an instrument Dotzauer played himself—would have gotten several pieces, but they all appear to be lost, and the list goes on…

The guitar occupies Dotzauer’s focus on the years 1810 (Op. 18), 1811 (Op. 21), and 1815 (Op. 31), before disappearing completely from his production. A natural question arises, asking whether there could have been a particular guitarist Dotzauer related to when he wrote them. To put it in a nutshell, it is not possible to answer this question for sure, but there are circumstances that may help explain the concentrated use of the guitar in those years.

Firstly, the guitar was in vogue in those years. Around the turn of the XIX century, the instrument finally got the outer appearance it has today, with six strings—compared to five, previously—and several improvements that made its sonority rounder and stronger. The epicentre of the guitar proved to be Vienna, although it managed to conquer the concert stage of London, Paris, and various other European locations. Many composers devoted themselves to creating works with and for an instrument that was becoming increasingly popular. The most outstanding ones were Mauro Giuliani (1781—1829) and Ferdinando Carulli (1770—1841), both of whom—by the way—also learned to play the cello1. On the other hand, many musicians taught themselves to play the guitar as a second or even third instrument, for example the double-bass virtuoso Domenico Dragonetti (1763—1846). We shouldn’t, then, forget about Niccolò Paganini (1782—1840), who was taught by his father to play the guitar and became a virtuoso on the violin as well as on the guitar.

There were hundreds of lesser known musicians, then, who performed on and wrote for the guitar. How broad the movement spread can be seen in the list of songs for voice(s) and guitar in the second edition of Carl Friedrich Whistling’s (1788—1855) Handbuch der musikalischen Literatur (1828), which, in category “BB” (vol. 3, p. 1107–1128), comprises more than 300 composers with their works and dozens of compilations. Dotzauer, being part of the trend with his two song cycles, is among them.

A detail often ignored is that music publishers normally only printed what they were sure to sell, that is, compositions that would have been found to be interesting for their customers. From letter exchanges between Dotzauer and publishers such as Simrock or Schott, we learn that the composer would have either proposed a variegated collection of works to be accepted (or rejected) by the publisher, or that they would have inquired on what they should write, based on popular demand. From these letters, we gain knowledge of many pieces by Dotzauer that will possibly forever be lost, such as a Concerto for Two Horns and Orchestra.

Among the renowned guitarists who could have influenced Dotzauer directly, we find Francesco Calegari (ca. 1798—ca. 1850) and Paolo Sandrini (1782—1813). Calegari was born in Firenze, Italy, but spent a considerable time in Leipzig, where he published his Sechs Lectionen für die Guitarre (Six Lessons for Guitar). Sandrini also came from Italy—he was born in Gorizia—, played guitar, flute, and oboe, and was a member of the Dresden Court Orchestra. He was also a respected composer, dedicating at least five compositions (opp. 12-14, 16, and 18) to the guitar.

We cannot definitely say whether there was a direct influence between all these great guitarists and Dotzauer or not. The most plausible explanation for Dotzauer’s use of the guitar, then, remains the fact that it was in vogue!

The Six Songs for Voice and Guitar, Op. 18

This collection of songs is titled Sechs Lieder mit Begleitung der Guitarre, 18tes Werk or “Six Songs with Guitar Accompaniment, Op. 18”. Just below, we find the dedication, to Madam Auguste Friederike Wilhelmine Dotzauer gebor. von Hopfgarten (Mrs. Dotzauer, born von Hopfgarten). She was the wife of Justus Friedrich Ludwig Ernst Dotzauer (1775—1818), the eldest brother of the composer. They got married in 1807 in Veilsdorf an der Werra, Thuringia. Dotzauer may have dedicated the songs to her because of her passable voice or because she respectably played the guitar, following the fashion floating through Europe in those years.

All six songs bear a simple form: a single musical phrase—except for N° 5 which is in a sort of simple ternary (ABA) form. The music is written only once, with the text found below and often flowing on another page. The guitar part is relatively easy, being possible to play it all in the first few positions. A student in their second or third year of study could have comfortably played them; the pedagogical spirit of Dotzauer may have taken the lead here.

Let’s now look at each song in greater detail.

N° 1 THEKLA. Eine Geisterstimme

This first song is in E major, in common time (c) with an upbeat of two quavers. It is marked with a tempo text of In mässiger Bewegung (in a moderate movement or, in Italian, “Moderato”). It has a comfortable range for a mezzo-soprano voice (or tenor) going from B3 to E5, and the accompaniment is made of continuous arpeggios. Each strophe is eight bars long, without any clear modulation, the most daring chord being a Dominant of the Supertonic (V/IV) in b 5.

The poem is THEKLA. Eine Geisterstimme (Thekla. The Voice of a Spirit) by Friedrich von Schiller (1759—1805), written in 1802 and published in 1805 in Leipzig2. This is the same Thekla von Wallenstein, daughter of Albrecht von Wallenstein, depicted in Schiller’s Wallenstein trilogy of dramas. It was set to music by several authors, the most famous being Franz Schubert (1797—1828), who wrote two different songs on the same text (D 73–August 23, 1813–and D 595–November 1817–). The poem includes six stanzas of four verses each, with rhyme following an ABAB scheme.

The voice of the narration comes from ‘beyond’ the grave. ‘Behind’ the veil of mortality, Thekla reassures us that, now that she has passed ‘over’, on the other side, all is well. Like her father before her, we have to see ‘through’ the illusion that deludes. An interesting, tragic choice for a poem to start the collection.

N° 2 DER PILGRIM

The second song switches to F major while retaining the same structure as the first one: eight bars in common time with two quavers as upbeat. Its tempo is marked as Mässig langsam (Moderately slow or, in Italian, “Moderato lento” or “Piuttosto lento”). The range is slightly narrower, from D4 to F5, and the overall rhythmical structure is very similar to that of the previous song. The accompaniment is, again, all in arpeggios but, harmonically speaking, this song is on an entirely different level than the previous one. Foremost, we start with a Dominant seventh chord, with the Tonic coming only in the second bar. We quickly veer towards D minor, which becomes D major in b 4 to serve as the Dominant of G minor. Another raised third favours the modulation to C, Dominant of F, for a final welcome back home.

The poem is Der Pilgrim (The Pilgrim) by Friedrich von Schiller, written and published in 18033. About four musical versions exist, the more famous being, once more, by Schubert in “Der Pilgrim” (No. 1 from Zwei Lieder, Op. 37 (D 794)), composed in 1823, and published in 1825). There is an interesting parallel between Schiller’s life and the description of the pilgrim’s journey in the poem, and, already after two songs, one may start to see some connections that Dotzauer may have wanted to draw between them and the dedicatee(s). The poem itself has nine stanzas of four verses each, with a circular ABAB rhyming pattern that helps the otherwise slow motion of the song move forward.

N° 3 AN DEN FRÜHLING

The third song is titled An den Frühling ([Ode] to Spring) and is marked Mit Heiterkeit (with cheerfulness or, in Italian, “con allegria”). It is in C major, with each strophe being allocated eight bars in 6/8 compound binary time alongside a quaver upbeat. The merry, joyful spirit is confirmed by the simple, yet effective, harmonic structure. The piece never truly modulates, rather using only a couple of secondary dominants. The vocal range is extremely narrow here, going from F-sharp4 to E5, less than one octave.

The text is taken from the poem An den Frühling, once more by Friedrich von Schiller. It consists of four stanzas of four verses each with the additional repetition of the first one at the end, and a free rhyming pattern. The poem was written by Schiller around 1780, and published in 17824. It was then republished twice, in 1805 and 1810 respectively5, with Dotzauer probably using the 1805 version. It was set to music by more than ten composers, most notably by Schubert (three times: D 283–September 6, 1815–, D 338 for TTBB quartet–circa 1816–, and D 587–October 1817) and, at around the same time as Dotzauer did, by Ferdinand Ries (1784—1838), in his Sechs Lieder Op. 7 (published 1810) for voice and piano (or guitar).

The inner sense of “arrival”, typical of Spring, is crucial to this text, tied in classical mythology to the return of Persephone from the underworld, where she had been held hostage by Hades. It is curious to see how Schiller describes spring as a beautiful young man rather than a fertility goddess like Persephone. This may be caused by the German word for spring, “der Frühling”, being a masculine noun (unlike the Italian “primavera”, which is feminine).

N° 4 MEIN

The fourth song is still in C major, in Common time, but with three quavers as upbeat. It is marked Etwas geschwind (quite fast or, in Italian, “Piuttosto rapido/veloce”) and, this time, gives the guitar a different kind of accompaniment: a bass note followed by a harmonic dyad. This makes sense because keeping an arpeggiated sequence throughout a faster piece would have proven quite more challenging compared to this solution. The harmonic journey of each eight-bar phrase starts briskly with a Dominant of the Submediant (V/vi) and a Double Dominant (V/V), before settling down a more peaceful path in the second half. The vocal range is once again modest, going from E4 to F5.

The text is taken from the poem Mein by Karl Friedrich Müchler (1763—1857). The task of hunting down this text was not trivial, for even if he wrote two volumes containing around fifty poems, the one used by Dotzauer was not there to be found. Thanks to a clever and narrow search in a specific library, it was possible to locate the first—and to my knowledge, only—appearance of this poem. It was inserted in the 44th issue (March 17) of the 7th year (1807) of publication of the Zeitung für die elegante Welt : Mode, Unterhaltung, Kunst, Theater (Newspaper for the elegant world: fashion, entertainment, art, theatre), in column 350 (page 269). Its structure comprises five stanzas of four verses each, the last of which is always made up of a single word: “mein”, with rhyming structure ABAB.

The poem tells the story of a person reflecting on their past and the loss of their youthful joy and innocence. They describe a beautiful time in their childhood that brought them happiness, but now they can no longer find that same joy in their heart. The poem portrays a sense of longing, loss, and unrequited love.

N° 5 STREITFRAGE DER LIEBE

The next song is the only one with a slightly more complex structure. This is due to each stanza of the poem bearing six verses instead of the four present before. The poem has four stanzas in total, and Dotzauer distributes three of them in the first part of the song (bb 1-12) and the fourth one in the conclusion (bb 13-24). We therefore have two musical periods of twelve bars each, with simple and effective harmonic choices that help the discourse move forward. It is in G major, in Common Time with a crotchet upbeat, and marked Im ungebundenen Zeitmas (in unbound time or, in Italian, “In tempo libero”).

The first period is divided in two halves by a double barline. The first half’s accompaniment is reduced to the bare minimum of a few isolated chords, leaving full freedom of expression to the voice. The second half, instead, is marked Mässig geschwind (moderately fast or, in Italian, “Moderatamente veloce”), and proposes the same accompaniment structure seen in N° 4, with a bass note followed by three plucked chords. The only harmonic stretches to be found are a Double Dominant (V/V) in b 5 and a Dominant of the Subdominant (V/IV) in b 9.

The second period bears the same division, but Dotzauer does not add a double barline this time. The rhythm is a direct copy of the first period, while the vocal line and the accompaniment are adapted to the different harmonic structure. One interesting difference is that the whole second part is marked Mässig geschwind, indicating that the first half (bb 13-18) should not be played freely. The vocal range goes from D4 to G5, making it substantially harder to manage than the previous songs.

The text comes from the poem Streitfrage der Liebe (The Controversy of Love) by Johann Stephen Schütze (1771—1839), published in 1810 in Leipzig6. Given the date of publication of Dotzauer’s song, this poem must have been available separately before the publication of Schütze’s collection. Schütze was a member of the circle of Johann Wolfgang Goethe and often visited the house of Arthur Schopenhauer. Four stanzas of six verses each compose the poem, with rhyming scheme ABBACC.

Overall, the poem explores the idea that love encompasses both the playful and physical aspects represented by the red mouth, as well as the deeper emotional and spiritual connection represented by the shining eyes. It suggests that both aspects are important and should be appreciated and valued in a loving relationship.

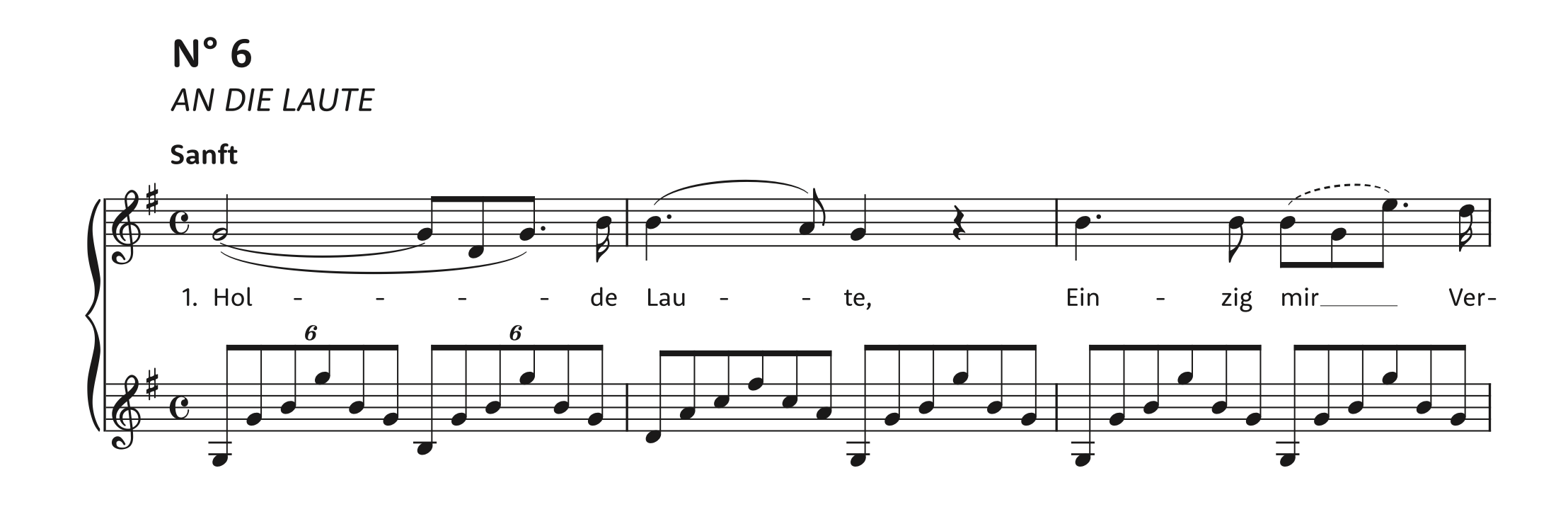

N° 6 AN DIE LAUTE

The last song of the collection is called An die Laute (To the lute), and it is an ode to the musical instrument of the same name. Dotzauer wrote it in G major, and it is the only song not to start with an upbeat, rather in a plain Common Time. It is marked Sanft (soft or, in Italian, “morbido, leggero”), with the musical phrase holding each stanza being twelve bars long. It uses the same arpeggiated accompaniment that we saw in songs n° 1, 2, and 3. The harmonic structure is elementary, with long passages of still chords where the entire burden of keeping the interest alive rests on the appoggiaturas and suspensions of the vocal line. The vocal range goes from D4 to E5, little more than one octave.

While the song is titled An die Laute, the first words of the first three stanzas are “Holde Laute” (gracious lute), which correspond to the original title of the poem by Christian Schreiber (1781—1857). Schreiber was a theologist, philosopher, philologist, poet, and translator from Eisenach, today’s Thuringia, Germany. The grand part of his multi-faceted production is entirely forgotten today, but he is certainly remembered for his authorship of the German text underlaid to Ludwig van Beethoven’s Mass in C major, Op. 86 (published by Breitkopf & Härtel in 1812). The poem used by Dotzauer appeared the first time in the magazine Der Freimüthige, oder Ernst und Scherz (the frank, or severity and pleasantry)7. There it bore the subtitle “Ein Lied für Componisten” (a song for composers), which was obviously meant as a call-up to set it into music. It was set into music by other composers such as Friedrich Methfessel (1771—1807), also for voice and guitar, Friedrich Ludwig Seidel (1765—1831), and Ferdinand Sieber (1822—1895). Other possibly more remembered composers melodised poems written by Schreiber, among whom we have to mention Franz Danzi (1763—1826) in his Opp. 19 & 46, and Ferdinand Ries in the aforementioned Op. 7.

The poem An die Laute consists of four stanzas, each of which having six lines. The rhyming scheme can be described as AABCBC in each single stanza, in which the two initial lines AA always rhyme with the same words: “Laute — Vertraute” (Lute — Familiar).

The poem describes the intimate relationship between the speaker (the poet?) and their lute, an instrument that serves as a confidant and a medium for expressing deep emotions. Dotzauer may have chosen this poem to close the collection to metaphorically express his gratitude to the guitar itself—as a rising star instrument—for allowing him to compose this music. Here, the lute (guitar) is personified as the only one able to understand the narrator, providing a wide range of emotions, evoking cherished memories, and, ultimately, offering silent understanding. Finally, the poet wishes to escape life’s sorrows through the musical creation act.

It would be fascinating to see the reaction of Dotzauer’s elder brother and of his newly acquired sister-in-law at the dedication of this collection, as the emotional temperature of each poem is, to say an understatement, peculiar.

About the edition

The realisation of this edition was possible thanks to the finding of a copy—possibly autograph—of the original text by Dotzauer, held in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BnF), and of a copy of the first edition, published by C. F. Peters in Leipzig in 1810, generously gifted by the Library of the Hochschüle für Musik Köln. The full score has been dutifully reconstructed following both sources and falling back to the autograph when in doubt.

This edition comes in a main book with a single insert. The main book contains these Editorial Notes, the full score of the six songs, and the text of the poems with English translation at the end. The insert contains a separate guitar part, to account for a single page-turn in the score being not ideal (Song N° 5). The beaming for the vocal part follows the classical convention of all music from before the XX century, and has intentionally not been modernised. The pagination has been switched from the landscape orientation of the sources to the modern portrait standard, and the text has been faithfully reproduced according to the sources. All differences between these and other versions of the poems, or between XIX century and modern German language, have been listed as footnotes in the text section at the end of this volume.

Acknowledgements

This edition would have not been possible without the invaluable contribution of Dr. Bernd Krause, the co-author of the updated voice on Dotzauer in the MGG encyclopaedia (Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart, or Music in the Past and in the Present). Dr. Krause, a trained cellist himself, is a musicologist and all-round researcher in history, and many of the information found in this edition would have been inaccessible without his help. He runs an “Office for Research in History”, Büro für Geschichtswissenschaften, which you can learn more about here8.

I would also like to thank M° Emanuele Buono of the Conservatorio “Antonio Vivaldi” in Alessandria, Italy, for analysing the guitar part and for describing to us the technical requirements behind the pieces.

A mention of gratitude goes to the personnel of the music libraries in Paris and Köln for making the purchase of and the access to the required material a smooth experience.

We hope that you will enjoy performing these songs and that this research will enrich the time you will spend in their company.

The Editor

Michele Galvagno

Saluzzo, Italy — April 13, 2024

- On December 8th, 1813 Giuliani performed as a cellist at the first performance of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony, conducted by the composer himself. ↩

- Gedichte von Friederich Schiller, Zweiter Theil, second, improved and expanded edition, Leipzig, 1805, with Siegfried Lebrecht Crusius, pages 31-32. ↩

- Gedichte von Friederich Schiller. Zweyter Theil. Leipzig, by Siegfried Lebrecht Crusius. 1803, pages 306-308; and with Friedrich Schillers sämmtliche Werke. Zehnter Band. Wien, 1810. Commissioned by Anton Doll, pages 190-191. ↩

- Anthologie auf das Jahr 1782, anonymously edited by Schiller with the fake publishing information “Gedrukt in der Buchdrukerei zu Tobolsko” (printed in the typography of Tobolsko), actually published by Johann Benedict Metzler in Stuttgart, pages 123-124. This poem has “M.” as the author’s name. ↩

- Friedrich Schillers sämmtliche Werke. Zehnter Band. Enthält: Gedichte. Zweyter Theil. Wien, 1810. Commissioned by Anton Doll, page 100; and Gedichte von Friederich Schiller, Zweiter Theil, second, improved and expanded edition, Leipzig, 1805, by Siegfried Lebrecht Crusius, pages 140-141. ↩

- “Streitfrage Der Liebe,” in Gedichte von St. Schütze (Leipzig, Germany: J. F. Gleditsch, 1810), 36–37. ↩

- Year 1806. Issue N° 2. Friday, January 3, 1806. Page 7. Digital edition accessible on MDZ here: https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/de/view/bsb10531329?page=16,17 — accessed on April 12, 2024. ↩

- Extended link for the printed edition: http://www.geschichtswissenschaften.com/. Accessed April 13, 2024. ↩

One thought on “Dotzauer Project – Episode 10”