Phonetic transcription (Part 2)

As we saw in one of the previous lessons, the Serbian language has a most useful peculiarity: you read what you write, you write what you speak! For someone coming from Latin-based languages (Italian, French, English, German, you name it), this is a blessing! We can imagine, though, how our languages may look and sound from a Serbian’s perspective. In this lesson, we will look at some phonemes and at how they are transcribed into graphemes in the different languages.

[k]

The sound [k] is always occlusive, velar, and unvoiced in Serbian, regardless of the vowels following it, and it is written as {k}1. Examples:

- кућа: home – casa

- коњ: horse – cavallo

- кекс: biscuit – biscotto

In Italian, the same sound can be represented as {c} when followed by a, o, u, as {ch} when followed by i, e, and {qu} or {cqu} in specific cases such as acqua (water, вода). The letter X is pronounced [iks] in Italian, and is represented by the {кс} group in Serbian.

[tʃi] and [tʃ]

The sound [tʃi] is written as ћ, while [tʃ] as ч. While they are similar, the first being softer and the second harder, I don’t agree with the book when it says that the soft one ћ corresponds to the Italian {ci} and {ce}. In Italian, we would never use such a soft {c}. Our sound is exactly in the middle of the two, making correct reproduction of both languages by non-natives much harder. In lesson 4, I came to the intuition that the accent of the vowel preceding these consonants can help us understand how to pronounce them. For starters—at least that’s how I’ve begun many years ago—, pronounce the hard one (ч) as if it would be a double letter.

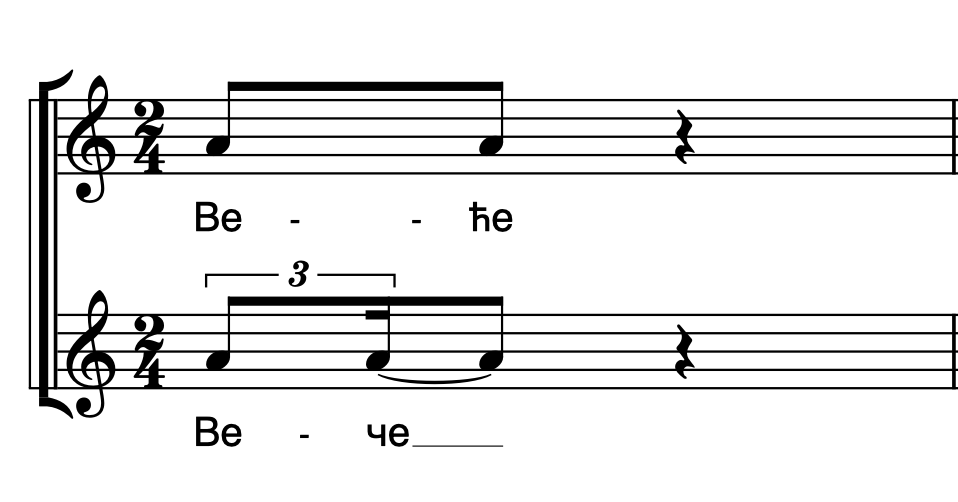

Musically speaking, I would think of the soft one (ћ) as downbeat, and of the hard one as slightly upbeat, but tied into the next beat (thus slightly longer), like this:

A few sample words:

- човек: man – uomo

- вече: evening – sera

- веће: bigger – più grande

You can see how the last two words may be almost impossible to distinguish by untrained ears. I am sure linguists will find this an abomination, but this is how I would try to learn these two words:

It may even be shorter, but it gives you an idea.

[x]

The unvoiced velar spirant, written in Cyrillic as an х, and in Latin as a h, is not pronounced in Italian. It is used in front of vowels to give them different meanings from their lonely counterpart, though:

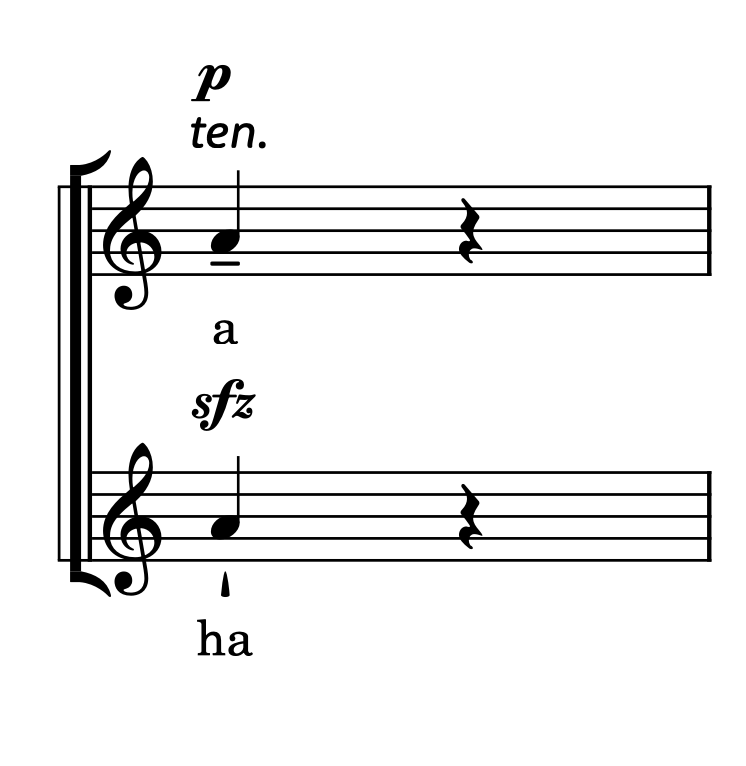

- A: preposition, equivalent to the English preposition “to”.

- Ha: third-person singular of the verb avere, “to have”.

The sound is distinctly different: the preposition is softer and slightly longer, the verb is harder, accented, almost harsh.

That said, the spirant H doesn’t exist in Italian, while it does in Serbian, for example:

- хлеб: bread – pane

- хвала: thank you – grazie

To practice this, try to substitute the H with a K, then progressively soften it until it becomes almost inaudible. It should work!

[g]

The letter {g}, which both in Italian and in English can be pronounced in two ways, has only one sound representation in Serbian, which is that of the unvoiced velar occlusive sound [g]. This is the same sound of the English “garden” (Giardino – башта) and of the Italian “gatto” (cat – мачак).

- Град: city – città

- гуска: goose – oca

- Ге-Дур2: G major – Sol maggiore

[dʑ] and [dʒ]

Before you get scared by the two symbols above, think of how you pronounce the letter J in English and know that the first one is a softer, almost smiling version of it, while the second one is harder and deeper. Once more, I don’t agree with the book saying that the soft G (Serbian: ђ) is similar to the Italian G found in ”gioia” (joy – радост) and ”gente” (people – људи). The Italian one is exactly in the middle, not too soft, not too hard (you know, we Italians have a hard time picking sides and sticking with it!).

To practice it, try to pronounce the J of “joy” with a forced wide smile. The tongue should slap your palate right behind your front upper teeth. That is the ђ. Now, try to form a rounded mouth, as if you had to pronounce U in a tribal way, and then pronounce the J of “Jupiter”, with as bass and deep a voice as you can. That’s the џ. I’m perfectly aware that I’m exaggerating here, but that’s the only way I could find to learn this myself.

- Ђаво: devil – diavolo

- џамија: mosque – moschea (the “ch” group in Italian is pronounced [k])

[λ] and [ɲ]

These two sounds exist in both Italian and Serbian, and in some circumstances in English as well. Serbian represents them with a single symbol in Cyrillic, љ and њ, and with a composite grapheme in Latin, lj and nj. These are equivalent to {gl} + {i} and {gn} + any vowel in Italian. In English, it is a bit more subtle, as the nj may be assimilated to the n in “new”. I am not aware of words that express lj as Italian and Serbian do.

- Љубав: love – amore

- сањати: to dream – sognare

And now, everyone’s favourite: “gnocchi”, which is not pronounced as “hard-G” + “nokki”, but as њоки!

[s], [z] and [ts]

In Italian, we have two kinds of S, one voiced and one unvoiced. The book says that the unvoiced one is that used in “Sun”, but from what I know, the opposite is true. The unvoiced one is, in Italian, written with a small dot under it, though you are not going to find it anywhere apart from in a dictionary (“Ṣ”).

Following the book, the [s] sound is written as с and is found in words such as:

- сунце: sun – sole (curiously, all three languages use a word that starts with the same letter, pronounced in the same way)

- свећа: candle – candela

- срећа: joy – gioia

The [z] sound, instead, is written as з (like a smaller number 3) and is found in words like:

- зора: dawn – alba

- зуб: tooth – dente

- зец: rabbit – coniglio

Finally, the [ts] sound is written as ц and used like so:

- цвет: flower – fiore

- црвен: red – rosso

- ципеле: shoes – scarpe

The [dz] sound found in “zero” in Italian is absent in Serbian.

[Ʒ]

This sound does not exist in Italian, but is borrowed when using foreign words such as garaGe or beiGe. The French j in Bonjour also used this sound. In Serbian, it uses the ж grapheme.

- Жаба: frog – rana

- живот: life – vita

[j]

This is easy: think of the Juventus Football Club. The way you pronounce that J is the same used in Serbian. To be fair, the Italian language had this grapheme until some time in the XIX century, completely fading out at the beginning of the XX century. Words such as ieri (јуче – yesterday) and gioia are pronounced as if they were written “jeri” and “gioja”.

Bottom Line

We went a bit long today, but I hope you found it worthy!

Thank you for sticking with me so far, I hope you liked it!

In the next lesson, we will delve into something new.

If you like what I do, feel free to share this article with your peers.

I also have a newsletter, dedicated mostly to my activity as a music engraver and sheet music publisher. You’re more than welcome to join!

I suggest you also give a look at the rest of my website, to see о чиме се бавим! 😉

See you (hopefully soon) for another lesson.