This article is an expanded version of the Editorial Notes that can be found in the published edition, available at this link. A promotional video of this score can be watched here.

EDITORIAL NOTES

Having plans when working on a gigantic task such as the Dotzauer Project is essential. Sometimes, though, they should be considered only as guidelines. The project’s first phase, covering the five books of pedagogical cello duets, was completed late last year (2022), while the second phase, on Dotzauer’s chamber music, started early this year with the Two String Quartets, Op. 12, and never progressed any further. Thereafter, the Russian Air with twenty variations, Op. 32, for two cellos, the Six Waltzes, Op. 17, for piano four-hands, and a couple of still unfinished projects got in the way. Since last year, the existence of a sixth book of pedagogical cello duets was discovered, even if its material appears to be lost—for now. Moreover, the feedback received from cello teachers at my seminar in Bari, Italy, in December 2023, convinced me that I had to expand and complete the first phase instead. Finally, my dear friend and colleague Yuriy Leonovich asked me if I could take care of Dotzauer’s Three Easy Sonatas for two cellos, Op. 103, to provide him with access to high-quality material for his lectures on the topic. It seemed, then, that the chamber music phase had to be paused, at least for now.

Hunting for the source

These sonatas are quite well-known among cellists, thanks to the IMC (International Music Company) reprint (plate 899) of the original Peters edition (plate 7439) curated by Alwin Schröder (1855–1928) being freely available online. This edition, though, was published around 1888–91, that is about thirty years after Dotzauer’s death (1860), and around sixty years after their original publication. The French edition, by Richault in Paris, is mentioned in the Bibliographie de la France1 at the end of 1829, while the first edition, by Friedrich Hofmeister, bearing plate number 1382 and lacking a publication date, appears to have originated at least one year before that (1827-8).

The final decision to realise a modern edition of this sonata-collection, when a version of it was already available to the public at no cost, came early in the comparing process. The fact that this was a good choice, though, received its confirmation only when, after completing the engraving of the Schröder’s version, close to 1200 differences were found.

A heartfelt “Thank You” goes to the library of the Conservatorio “Vecchi—Tonelli” of Modena, Italy, for granting us access to the original Hofmeister edition. To this day, no trace of the manuscript has been publicly classified.

The Three Sonatas

Despite the deceptively compelling title, these sonatas are impressive works: 1224 bars in total, and about 45 minutes of playing time when including repeats. They all use the canonical sonata form of the late-Classical period, with a first movement in Allegro-form, a second, slower movement with a lyrical character, and a third, fast, closing movement, usually in Rondò-form.

The original title found on the cover of the Hofmeister edition from 1827 recites, in French: Trois | Sonates | FACILES | pour le | Violoncelle | avec Accompagnement | d’un second Violoncelle | composées | PAR | J. J. F. DOTZAUER. Being aware of this title is critical, given that the Schröder edition takes away the “easy” portion and alters the instrumentation to “two cellos”. The soloist character of these pieces is thus removed from them, tricking the reader into thinking these to be duets, where both parts have a similar weight. It is certainly not the case for these sonatas, where the accompanying cello has very few—if any—moments to shine compared to the obbligato cello.

The adjective “easy” is clearly referring to the left-hand technique needed to play these sonatas: nothing higher than the fourth position is required of the player, if one accepts the occasional jump to the central harmonic as the exception that confirms the rule. A few double-stops, nothing extraordinary, enrich an otherwise smooth and enjoyable playing.

The right-hand technique is a different beast, though, especially in the slower movements, where significant differences in bow speeds give the learner a rough ride. While practicing these sonatas, I realised the noticeable disparity in complexity between the two hands may have caused their dropping out of fashion. By the time a cellist achieves the right-hand technique level needed to play these sonatas with ease, their left-hand technique should already be much further than the fourth position. Schröder changed several bowings, but his contribution did not make these sonatas any easier to practice. If anything, they only prevented us and every cellist who practiced on his version—basically everyone from the XX century onwards—from understanding what Dotzauer truly wanted.

Nevertheless, I believe these to be a worthy addition to every cellist’s repertoire for a simple reason: their beauty! Regardless of the possible benefits to one’s technique, these pieces are full of memorable themes, and provide the perfect material for a couple of professional cellists needing something their audience will not forget and that they will not struggle too much to prepare. They also sound as much more mature pieces than the marketing behind their title would suggest.

Overview

All three sonatas are set in major keys: the first one in G major, the second one in C major, and the third one in F major. The first sonata has the following structure:

- Allegro, C, 126 bb. — Sonata-Allegro form.

- Andante, 6/8, 51 bb. — Rounded Binary form, written out in full due to the differences in the ending, enclosing a middle section in F major between two C major parts.

- RONDÒ. Allegro, 2/4, 208 bb. Rondò form: A-B-A-C (in E moll) and an expanded A with a short coda.

The second sonata, in C major, starts with an Allegro in Common time, 135 bars long, in Sonata-Allegro form. The second movement, Andante, is, actually, only a 16-bars-long introduction, albeit in C minor and in 6/8 time, to the final Allegro. This, again in Common time, clocks at 206 bars and is rich with repeated structures. It also contains a section in F major and another in A-flat major.

The third sonata, in F major, starts with an Allegro in simple triple meter (3/4) which is 207 bars long, with a dancing bridge in the exposition that will fuel most upcoming material. This is followed by the most complex movement of the collection, an Andante in D major, which is actually a theme and variations without the proper labels announcing the sections. This may be the only movement to pose real challenges to the player, especially from the bow-management side, but is also, perhaps, the most beautiful one. The FINALE. Allegro that closes this Sonata is in 6/8, with a half-bar upbeat, and totalling 177 bars in a Rondò form. It follows basically the same structure of the Rondò from the first sonata, with the only difference that, here, part C is much richer and daring in its modulations.

Let’s now dive deep into each of these three sonatas.

Sonata n° 1 in G major

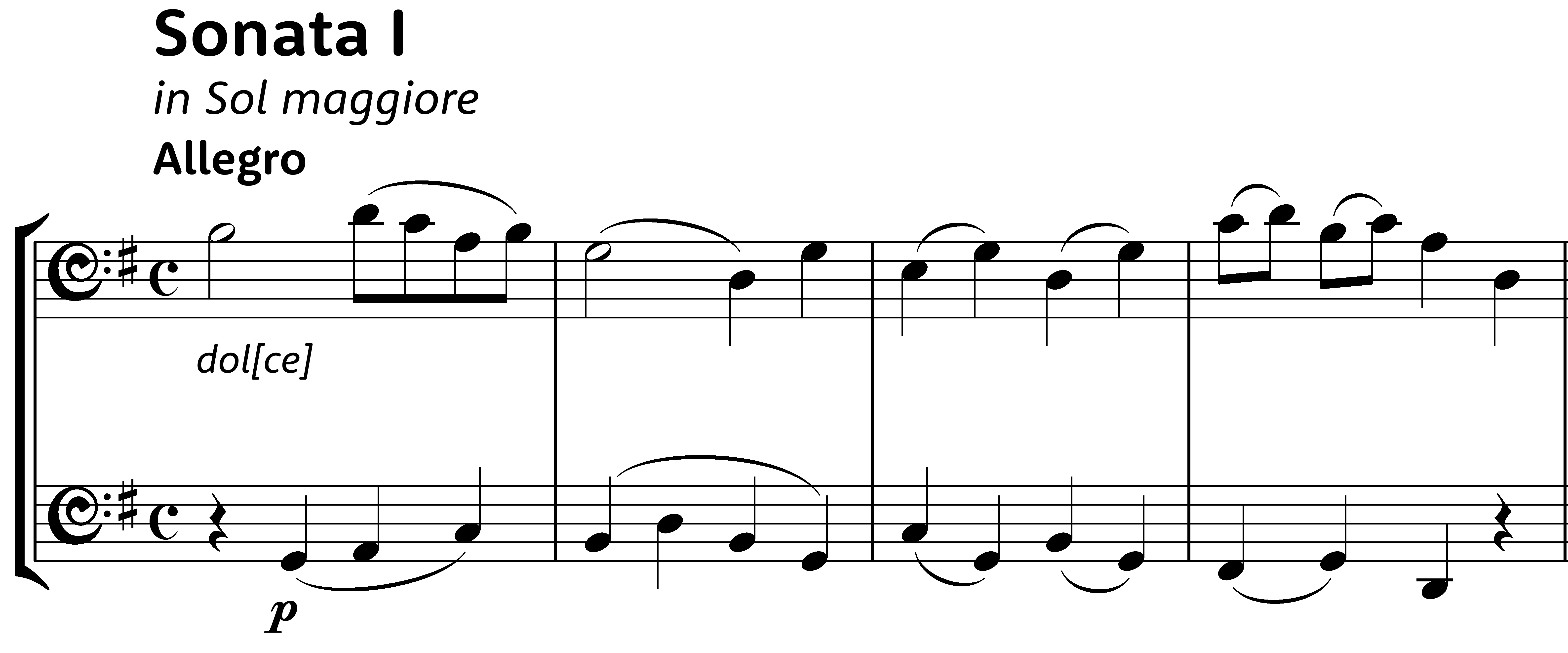

The first movement, Allegro, opens with a singing melody accompanied by a regular counterpoint in the basso line.

The exposition of the theme is fairly long, 24 bars, with the incipit coming back three times. The connecting bridge that follows appears to be wanting to build upon the melodic foundation of the opening melody, but is suddenly pushed aside by an aggressive modulation to D major, using, among other things, augmented sixth intervals. The second theme starts after a fermata and is, as expected, of a contrasting character:

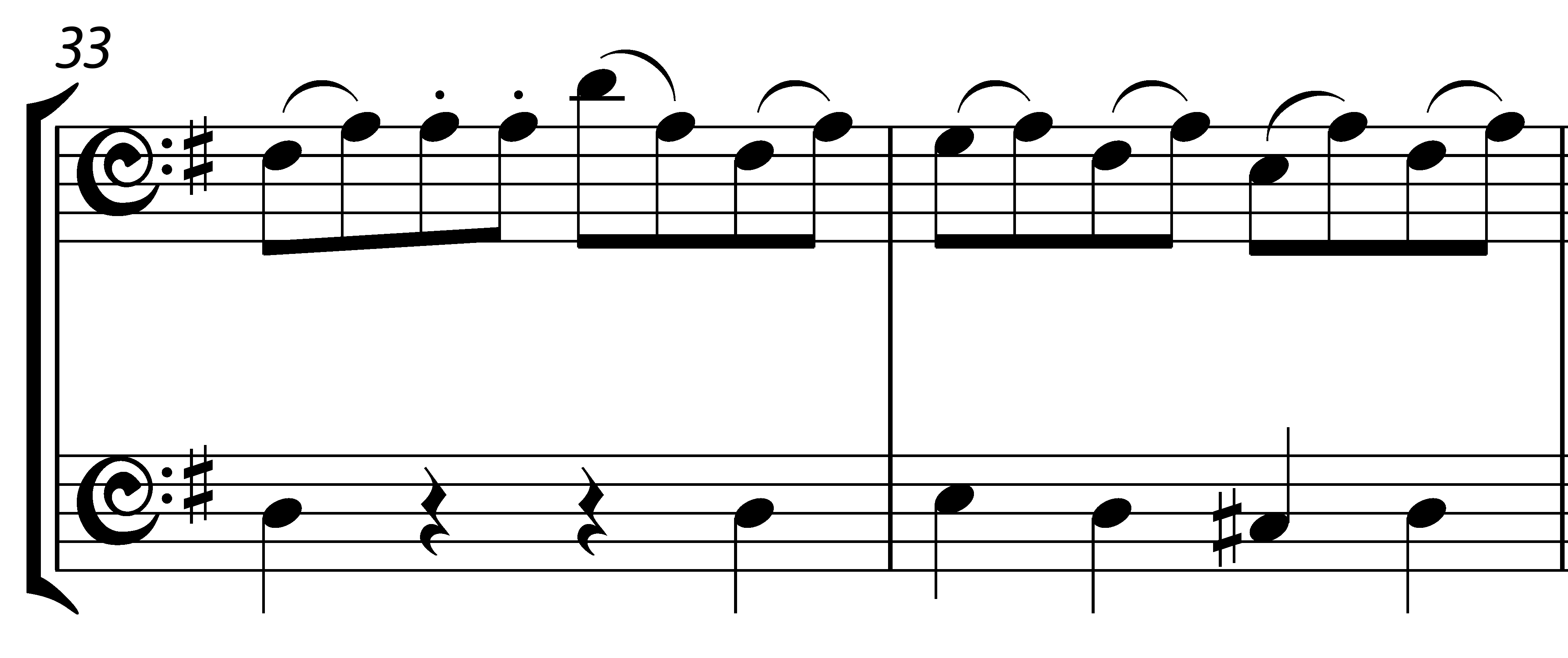

There is no coda of the exposition before the repeat line, with the development then breaking in with a sudden forte line. The rhythm of the second theme is given to the basso, while the obbligato cello elaborates on the first idea:

The modulating journey covers A minor, E minor, B minor (with yet another evolution in augmentation of the first theme), before a short 8-bar bridge introduces the recapitulation. The two themes are this time proposed in quick succession, without any bridge, with the rhythm of the second theme continuing until the end of the movement, which concludes without a coda.

The second movement, Andante, chooses a melody that requires a singing line also in the basso to feel complete. The rhythmical structure is in 6/8, with a quaver upbeat.

This theme, in two 8-bars repeated sections, is simple, never leaving the safety of the home key. The B part of this rounded-binary form changes the key to F major, and doubles the rhythm in a seamless run of semiquavers. The bowings recommended by Dotzauer are just perfect, and should not be changed, as they can teach a lot about proper bow management. The two sections of this second part are four and eight bars long, respectively, and both have repeats. Part A, then, makes its comeback with both sections unrepeated, and an amusing 7-bars-long coda.

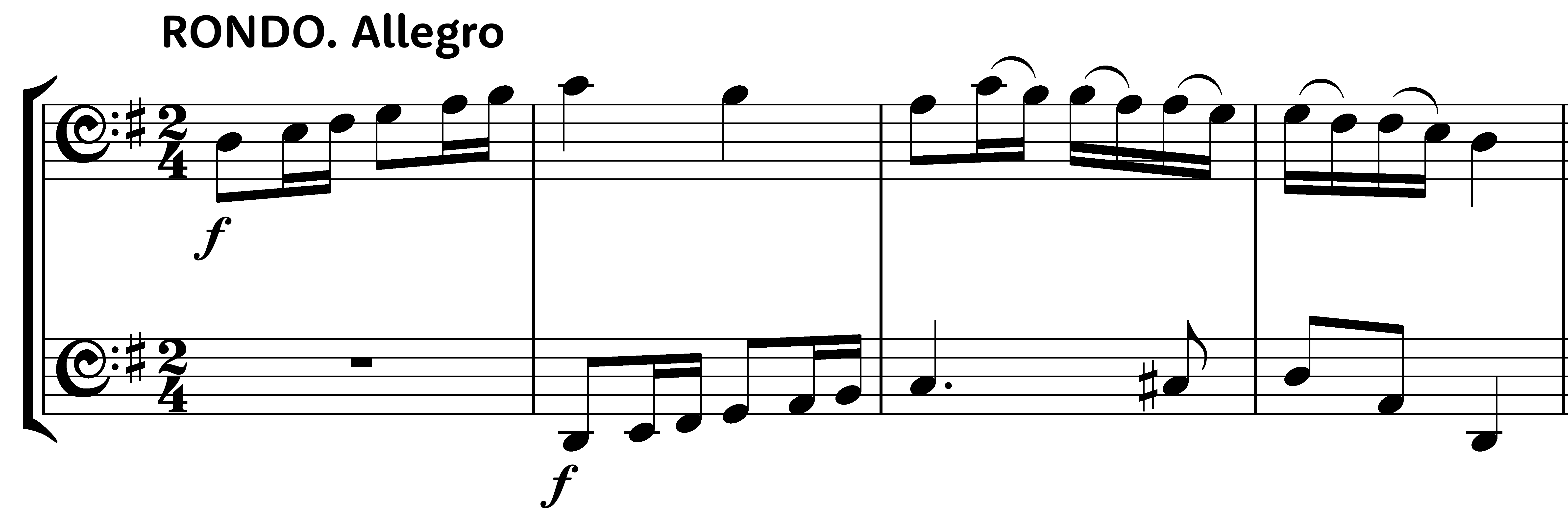

The final movement, Allegro, bears the authentic signature of Dotzauer: a contrapuntal beginning.

While remaining all in the safety of the first four positions, this Rondò offers several opportunities for exercising fingers articulation. The opening A part, with two repeated 8-bars-long periods, is followed by a strongly modulating B part which alternates melodic and rhythmic lines. It touches C major as a secondary dominant then, from the home key of G major, veers towards a chromatically enhanced D major. A short transition brings back the A part, this time only showing the first eight bars. The subsequent Part C, clearly in E minor, begins with yet another contrapuntal idea:

Everything here is a continuous catch-up game, where equal passages are shown to be possible with opposite bowings one after the other. When A comes back, one last time, the accompaniment enriches the imitation with filling bassoon-like quavers, before a final, epic crescendo brings this first sonata to a close.

Sonata n° 2 in C major

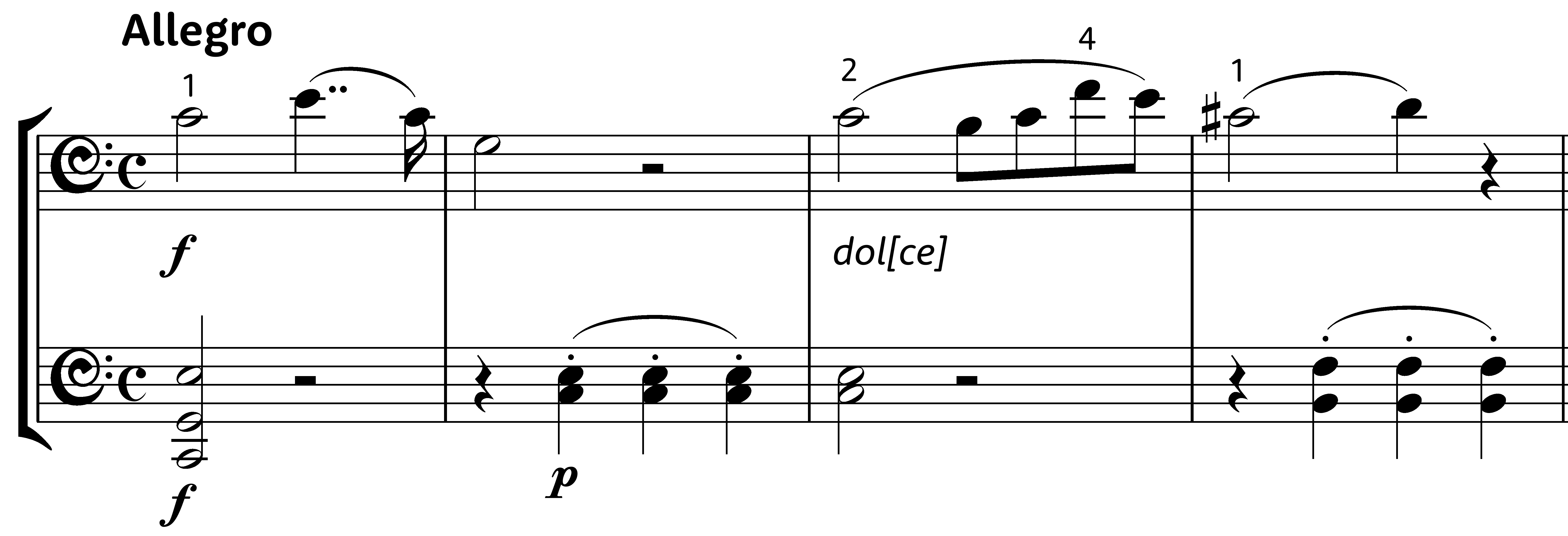

After archiving the first sonata as a warm-up, Dotzauer resolves to begin the second one with a heroic, almost pathetic gesture:

The first, loudest, chordal exclamation is immediately followed by a soft, alluring, melodic line. This almost looks like an introduction to the chromatic line that will constitute the modulating bridge, while the accompaniment supports the chant with regular quavers throughout.

The second thematic idea comes once more after a fermata, and is based in the dominant key of G major:

It retains the chordal outline of the first theme, adding triplets to the mix. These triplets will accompany us until the end of the exposition, with a clever alternation of arpeggio and melodic lines.

The development uses the material of the second half of the first theme as ingredients to propel the musical discourse forward. This is also the first time when the basso has a single chance to shine, with the melody expressed low on the third string. Then, all of a sudden, triplets come back, in a long harmonic progression that touches F major, G minor, A-flat major, B-flat major, and C minor, until a dominant chord leaves room for the obbligato cello to bring us back to the recapitulation with a chromatic scale. This time, the scale of the bridge between the first and second theme is simply impressive. With the second theme expected to be in the home key of C major, Dotzauer explores F major/minor, then G major/minor, before finally allowing the triplets to appear, this time without the need of a fermata. The closing coda is very short, and the whole movement ends with the duo playing a descending arpeggio in octaves before the concluding perfect cadence.

The second movement, Andante, is very short and only serves the purpose of introducing the long, final Allegro. It is in C minor, in 6/8 time, and very challenging for intonation:

The closing movement, in Common time, shouldn’t be taken too slowly or its length will make it difficult for the listener to stay concentrated on it. Its form could be loosely approximated to that of a Rondò, but Dotzauer enriches it with several creative solutions. It begins with a rather simple melody:

The three periods that constitute what we could call Part B are all 8-bars long and with repeats, respectively journeying through A minor, F major, and D minor, with a key signature change to one flat. A short, almost improvised bridge brings back the opening theme in its entirety. At this point, we have another key signature change, this time to A-flat major:

While the obbligato cello sings its melody, the basso follows with a heavily chromatic accompaniment, all in crotchets. The opening rhythm comes back at the end of this part (C), but C major has not yet managed to regain its throne. When Part A finally makes its comeback, it also brings with it the first third of Part B (the A minor section), before launching into a spectacular coda that concludes the sonata.

Sonata n° 3 in F major

The last sonata of the collection is the only one with the first movement (Allegro) in simple ternary time (3/4). It opens with a pastoral dance motif, with the basso playing a drum-like accompaniment:

The bridge between the two themes is worth mentioning because it will be at the base of the development section:

After this apparently innocent unison entrance, the motif breaks between the two instruments, which then begin following each other contrapuntally. We will encounter this again soon, but now it’s time to hear the second theme, in the Dominant key of C major, with the basso playing a waltz-like accompaniment:

Triplets make their appearance in the coda of the exposition, with the development abruptly making space through the upbeat motif of the first bridge. It seems we could go to D minor; instead, a jibe at the last moment veers towards an exhibition of the second theme in B-flat major. Through several reiterations of this motif, we visit the keys of C major, D minor, A minor with hints of the B minor that will follow immediately after, and F-sharp minor. A deceptive cadence in this last one (C-sharp to D) introduces a new section of this rich development, this time based on the upbeat motif of the bridge. Dotzauer uses this to modulate through D major (the submediant of F-sharp minor), G minor, C major, and A minor. At this point, he brilliantly proposes a false recapitulation in A minor, an 18-bars section where the listener is cunningly deceived into believing we have already reached the conclusion.

The real recapitulation follows suit, with the two themes both in F major and with no bridge connecting them, and with the triplets poking their heads at the last minute, just in time to join the celebration.

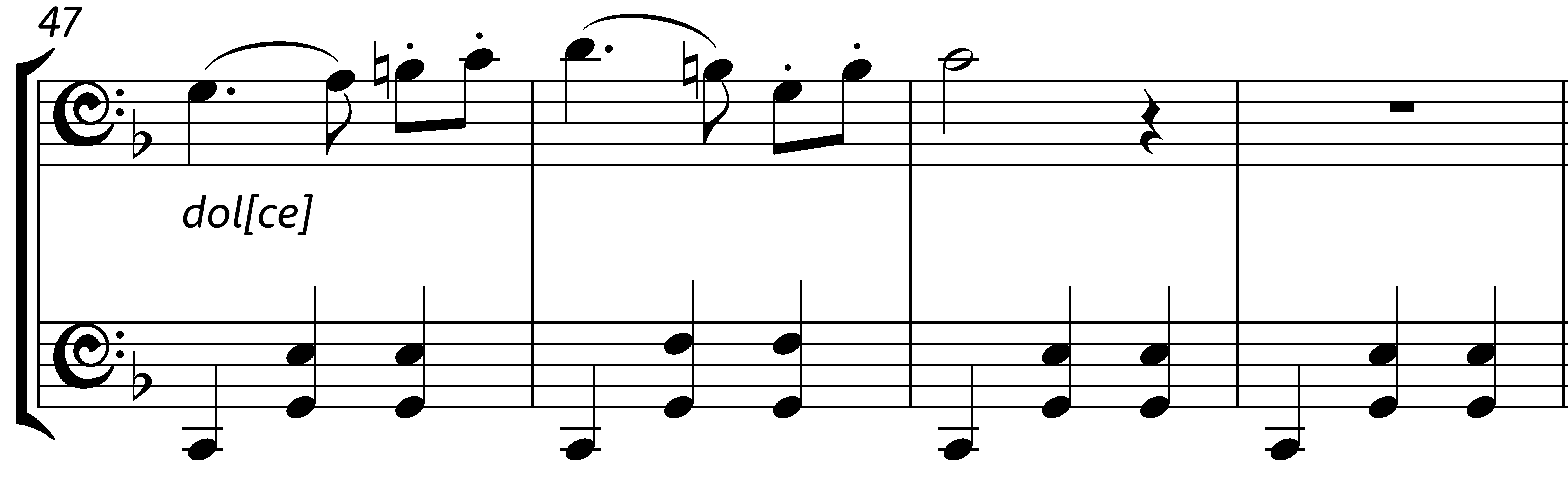

As stated above, the second movement (Andante) of this sonata is the longest one of the whole collection, and the most technically demanding as well. This is already crystal clear from the start:

The choice of speed is also crucial here because the slower one takes this, the harder bow management will become, while going too fast will cause troubles towards the end. The key choice is peculiar and, we can say, finally Romantic, with a descent of a minor third from the home key of the sonata (D major from F major). The basso is much more involved than usual as well, with the second half of the theme gliding through several related keys in continuous contrary motion.

The first variation starts in b 17 with an apparently innocent decoration of the original melody, while the accompaniment modifies only the notes needed to make sense of the harmonic procedure. While both the theme and the first variations were in two parts, each with the repeat mark, what comes next is quite original, even though it could still be considered as a second variation. It is constructed in D minor, the relative minor key of the sonata’s home key, and contains the apex of the movement in the form of a 14-bar section where the obbligato cello shows its technical prowess over a dominant pedal enriched by lowered submediants.

The triplets that ended this part continue in the third variation, back in D major and clearly connected to the original theme also through the formal repeats of the two 8-bar sections. The coda that follows is the only moment when we have double stops used melodically, with triplets never abandoning us until the very last moment.

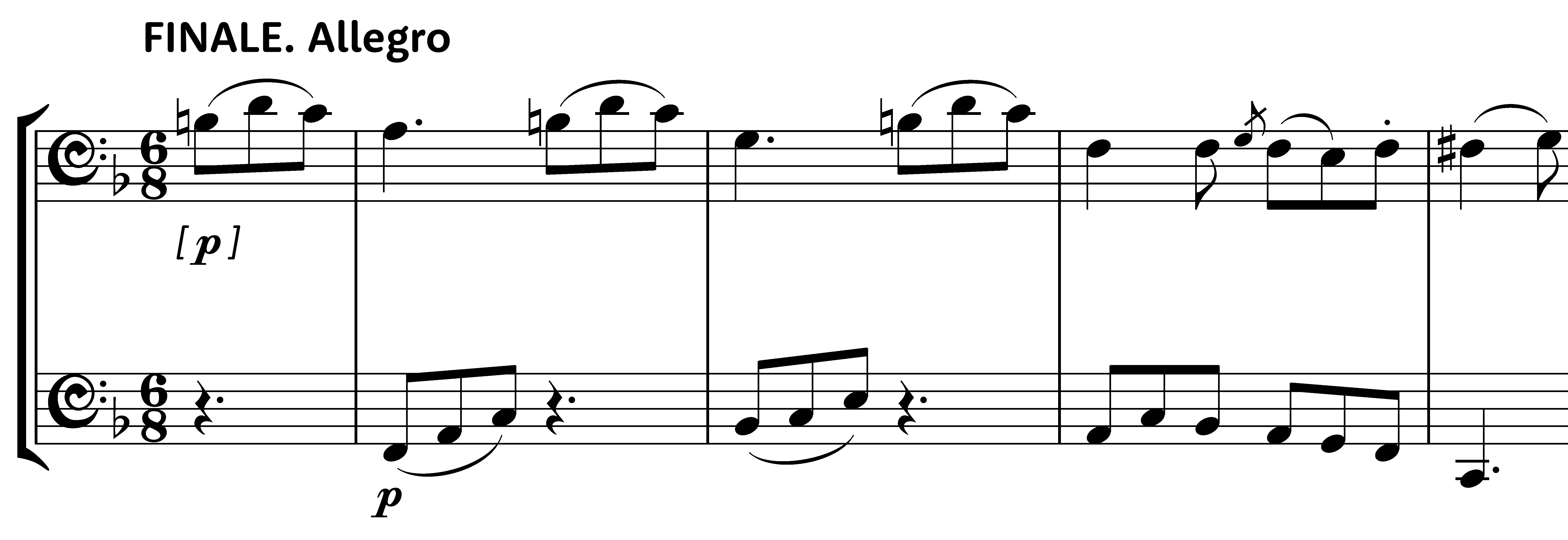

The third movement, labelled FINALE. Allegro, is once more a Rondò, is back in the home key of F major, and is in compound binary time (6/8) starting, though, with half a bar of upbeat. It is possibly the weakest one melodically, but it compensates with the ingenuity of the musical construction.

Exactly as with the previous finales, two 8-bar sections form the opening Part A, both of them with repeats. The Part B that follows uses the three-quaver figures passing through the two instruments as a propeller for a tonality journey that touches D minor, A minor, G major, and finally C major. A new idea emerges just before the return of the opening theme, with both parts offering something unique:

A unison rush of F major Dominant arpeggios brings us to a short recapitulation where only the first eight bars of the main theme are proposed, this time without a repeat. Part C is an 80-bars-long mastodon in which materials both familiar and new are thrown into the arena. It commences with a reprise of the main theme in D minor, which quickly veers towards B-flat major with a new idea:

The double stops then make a comeback in the next section, ranging from B-flat major to G minor, with a deceptive cadence bridging to E-flat major. Through the lowering of the third (G to G-flat) and its enharmonic equivalence to F-sharp, we are hurled straight into B minor, until a short, fugue-like, G major excerpt tries to bring back some order. The double stops in the accompaniment signal that it’s time to change, and here comes back the main theme. The recapitulation lasts only eight bars, and the first period of C also makes a brief appearance, before the unison rush that closed Part B is called back to draw the curtain over this fascinating collection.

About this edition

This edition comes in two main versions: Standard and Collectors’ Edition. The Standard version is based on the closest surviving source, the Hofmeister edition (plate 1382), and contains a score and a set of parts in its modern adaptation. Its uniqueness—besides the design upgrade and the errors’ correction—stands in it offering a full score for the first time. There is also a Critical Commentary at the end of the score.

The Collectors’ Edition, instead, contains two more copies of both score and parts, one based on Alwin Schroeder’s version, from Peter’s edition (plate 7439) and one with my personal bowing and fingering suggestions. The digital version of the Collectors’ Edition, furthermore, includes a PDF of the score that highlights where changes were made, making it incredibly simple to find whether a certain spot was altered from the original intent of the composer. At the end of each of the two additional scores, finally, is a comprehensive list of all changes compared to the first edition.

Any evident error has been corrected without further notice, while editorial additions have been marked within square brackets.

I hope having finally access to the original source of these sonatas will show how fundamental their presence can be in every cellist’s arsenal.

The Editor,

Michele Galvagno

Saluzzo, December 19th, 2023

- Bibliographie de la France 1e série, 18e année (32e de la collection), Nº 38, 19 septembre 1829, p.640, r.251. ↩

2 thoughts on “Dotzauer Project – Episode 9: announcing the “Three Easy Sonatas” for two cellos, Op. 103”