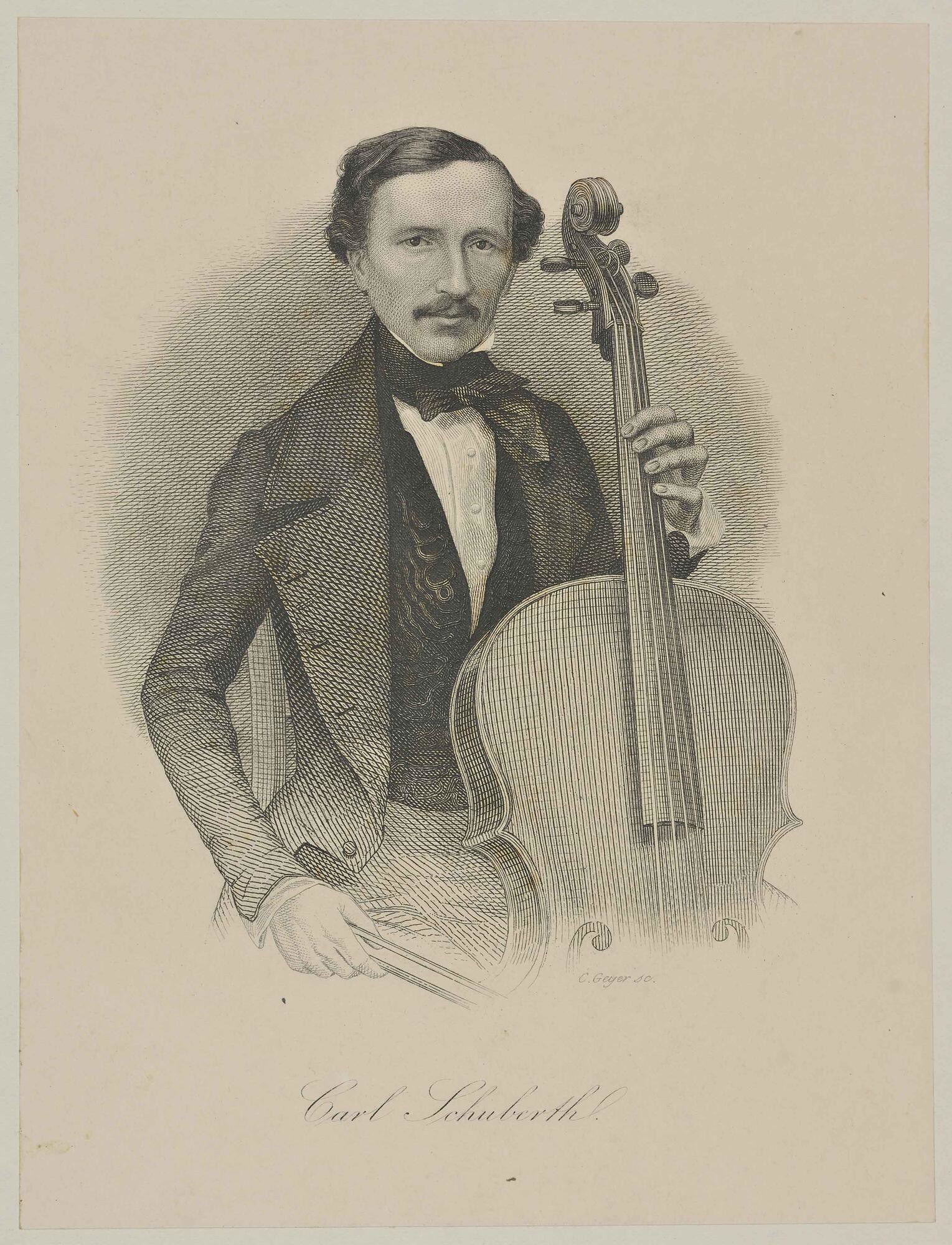

direct descendant of the cellist Carl Eduard Schuberth

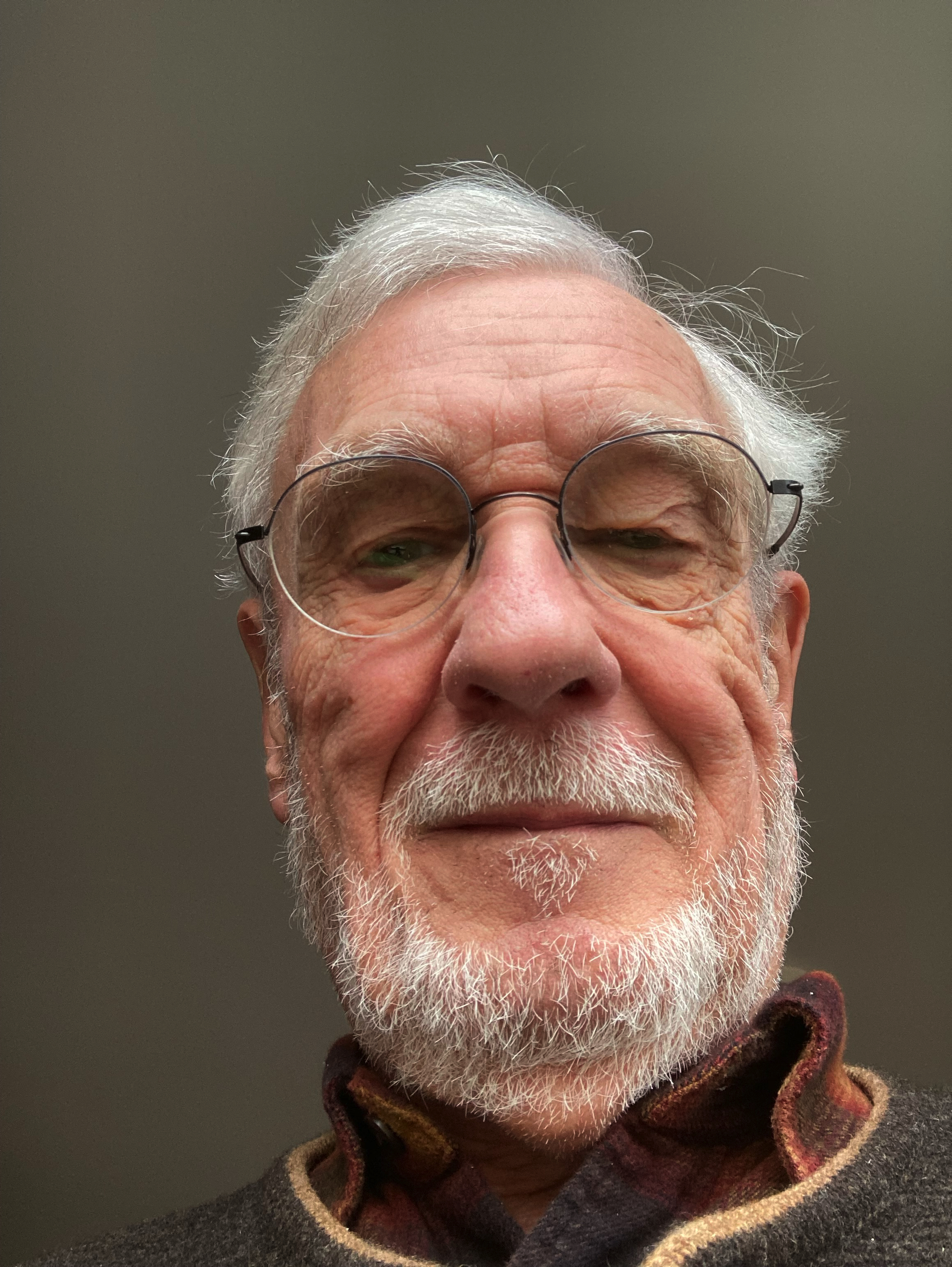

Hello everyone and welcome back to the blog. Today, I have the honour to sit down and chat with Michel Schuberth, a direct descendant of the German cellist Carl Eduard Schuberth (1811–63), student of J. J. F. Dotzauer and legitimate founder of the Russian Cello School. Michel conducted a thorough research on his ancestor and, while looking for more details on the Dresden Cello School, he found our newsletter. His work of revaluation of Carl Schuberth’s work is remarkable and includes conferences, concerts, recordings, and, from now, publications!

Today, the 25th of February, coincides with Carl Schuberth’s birthday and, alongside this interview, we decided to release the first modern edition of his music, the Souvenir de la Hollande, Op. 3, in its version for cello and piano. Please find more on this edition here or here, enjoy a promo video, and watch this space for the announcement of the printed book.

Now, without further ado, let’s get started with the interview. Please sit back, relax, and enjoy the ride.

Dear Michel, thank you for joining us today, it is a pleasure to have you here. You contacted me in 2024 manifesting your interest in Artistic Score Engraving (ASE)’s research and publishing initiative around the Dresden Cello School. Without spoiling anything, would you please introduce yourself, and tell us something about you and your research?

After a long commercial career in the field of graphic arts and publishing, I am now retired. I am descended through my father from the cellist Carl Schuberth. Originally from Prussia, he settled in St. Petersburg in 1836 and gave birth to the Russian branch of our family. I am not a musician, but I have always loved classical music, and it was chance that led me to undertake research on my ancestors and more particularly on Carl Schuberth. From my early youth, I had heard my parents mention “a musician ancestor of Prussian origin who lived in Saint Petersburg”. This had a profound impact on my childhood imagination and, as a young man, I undertook various searches but without success. I always came back to Hugo Riemann’s old music dictionary where there was a brief article retracing the lives of Carl, his father Gottlob and his brother Julius, all three musicians. Carl was always my favorite because he played the cello, my favorite instrument, but also for the audacity he showed in leaving his native Prussia to settle in distant Russia. In 2018, during a chance visit to the Matthias Church in Budapest, I discovered in a display cabinet the score of the Coronation Mass of Franz Joseph and Sisi, composed by Franz Liszt. Surprise: the score was edited by Julius Schuberth, Carl’s older brother. My curiosity was piqued, and the Internet quickly revealed a plethora of information about the Schuberth siblings. What was supposed to be only a final attempt to satisfy my filial curiosity quickly transformed into a long and fascinating research revealing the stature of a forgotten musician. Considered one of the most talented cellists of his time, he contributed to the musical life of the XIX century in Europe and Russia. This is how my youthful questions took shape, and I managed to get to know my great-great-grandfather better. To this day, I continue with the same enthusiasm my research started in 2018.

It was delightful to read the (currently unpublished) research on your ancestor, enriched by a treasure trove of connecting facts. We both know the daily amount of struggle we face when searching for reliable sources during our researches: please elaborate on what were the greatest obstacles in your path. What, instead, were the most positive encounters along your journey?

As mentioned, for a very long time, my quest for information came up against two pitfalls: locating sources and accessing them. These major obstacles have been largely swept away by the appearance of the Internet and search engines. Add to this the flexibility of communication via e-mail and the emergence of translation tools. Although these tools are not perfect, they nevertheless open up incredible possibilities for researchers. The task remains no less laborious, but it is fascinating, even if any discovery requires scrupulous verification.

Now that we warmed up, let’s focus directly on your ancestor, Carl Eduard Schuberth. While there exist several studies on the Dresden Cello School, they are plagued by a wealth of incorrect and inconsistent details, making the reconstruction of a coherent story a true challenge. Please enlighten us on your ancestor’s story, with a particular focus on how he could be regarded as the founder of the Russian Cello School.

Reconstructing a coherent story is indeed a real challenge. Fortunately for me, in 1847 on the eve of Carl Schuberth’s tour in Germany, Julius Schuberth, the music publisher, published in his periodical Kleine Musikzeitung a long story entitled “Carl Schuberth in Saint Petersburg – Sketch of a Life”, which I was able to get my hands on at the New York Public Library. Julius retraces with humor and kindness Carl’s formative years, his first tours in Europe and his beginnings in Russia. As for the rest of Carl’s journey, the research was much more laborious. I did extensive research in the press of the time and other publications (in German, Russian, English, and French), and this is how I was able to put together a chronology retracing his journey in Russia from 1836 until his unexpected death in 1863. Valuable personal information from the Russian National Archives was conveniently added. This bustling period corresponds to the “Golden Age” of Russian music of which Carl Schuberth was, as a cellist, quartet player, conductor, composer, concert and tireless teacher, both the privileged witness and an actor unavoidable. Carl Schuberth was above all remembered as an exceptional cellist and a teacher who counted Karl Davydov (1838–89) primarily among his students. His activities as a conductor and composer are also well documented. My research also revealed the actions he took to make music accessible to all audiences and professionalise his teaching. The concert cycles that he put together trained the ear of a whole generation of soloists and composers to Western music, and he collaborated closely with the pianist Anton Rubinstein (1829–94)1 in the creation of the Russian Musical Society. This institution was the main vector of progress in musical life in Russia and gave birth to the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, the first in Russia. Due to the historical events that marked the XX century, the essential contribution of foreign musicians to the development of Russian musical life has been largely obscured. Carl Schuberth was undeniably one of the musicians “unfairly excluded”. He has recently regained his place in collective memory, both in Russia and in Germany. Today he is not only recognised as a cellist, conductor and pedagogue, but also as the legitimate founder of the Russian Cello School and co-founder of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory. His works are little by little being rediscovered and replayed, and that pleases me a lot.

One of the focuses of our publishing initiative is the Dotzauer Project. Your research reveals several details of your ancestors’ apprenticeship with Justus Johann Friedrich Dotzauer, including a few amusing anecdotes. Would you like to share something of that with us?

Carl Schuberth is considered one of the most talented students of Justus Johann Friedrich Dotzauer (1783-1860) from Dresden. Little is known about his relationship with his master, but undeniably the demands and severity were there. Apparently, Dotzauer’s students lived under his roof and were therefore constantly under the watchful eye of the master. The daily practice of his “Studies” must sometimes have seemed tedious to Carl, but later he fully appreciated its importance. In 1828, he returned to Magdeburg after two years of intense studies and during the summer he gave a series of concerts which were very successful. Building on these first laurels, he decreed that he would not set foot in Dresden again, but Julius quickly put him back on the right path by promising to organise a major tour for him if he completed his course. This is how Carl returned to Dresden to complete his training, and the future showed that the decision had been wise.

Where can our readers find more about your research, the recordings, and the concerts you are promoting? Can you share something of what’s in store for the near future?

As soon as I have finalised my biographical document on Carl Schuberth, I plan to write a summary and insert it on Wikipedia, the free encyclopaedia. There are already two articles, one in Russian and the other in German. The first is incomplete and should be increased, the second contains errors which require rectification. I will add a link to my biographical document to make it accessible to everyone. Works will be listed with links to existing recordings. As for the concerts, I try to give as much visibility as possible to their programming. I also note an increase in announcements and articles on the internet, which is very encouraging.

The older brother of your ancestor, Julius, was a very famous music publisher in the XIX century, and it is thanks to him if we have some of the best editions of the later Dotzauer works, among other things. Would you kindly tell us how Julius’s figure was crucial in Carl’s career both as a cellist and as a composer?

Julius was seven years Carl’s senior. He was a true mentor for his younger brother. Their father Gottlob, too absorbed in teaching the oboe and clarinet, relied very early on Julius to oversee the education of his younger brother. Julius was a recognised publisher and had access to all the high places of European musical life. Not only did he ensure that his boisterous little brother worked hard and followed the teaching of his teacher Friedrich Dotzauer to the end, but it was also he who organised and financed the tours that Carl made from 1833 to 1835, and which took him notably to several cities in Germany, to Gothenburg, Amsterdam, Brussels, Paris, and London. Once settled in St. Petersburg, Carl returned the favour by promoting his publishing house to his fellow composers. Numerous epistolary exchanges and articles published by Julius in the specialised press testify to this synergy within the siblings. J. Schuberth & C° was also the exclusive publisher of Carl’s works.

Our goal, now, is to publish new, modern, critical editions of Carl Schuberth’s works, so that they may find their way back to the stage where they rightfully belong. I am sure our readers will love to see the fruits of our new collaboration together. Is there anything you would like to add before we sign off? Where can people find you and learn more about your research?

Artistic Score Engraving and your research and publication initiative on the Dresden Cello School constitute a great step forward in the field of publishing, and I hope that our collaboration will provide some enlightening elements. If readers would like more information on Carl Schuberth’s background, I suggest that you forward inquiries to me or that they contact me directly by email at mschuberth [at] hotmail [dot] com. I hope to have answered your questions, and thank you particularly for granting me this interview.

Thank you for the time you gifted us today. It was a real honour to have you here with me.

2 thoughts on “A Conversation with Michel Schuberth”