Hello everyone and welcome back to the blog. Today, I have the chance to sit down and chat with Melbourne-based composer Lee Bradshaw, with whom I have had the honour of collaborating with on several projects over the past few years.

Lee’s first opera, Zarqa Al Yamama, will be premiered in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, on April 24th, 2024, and it is a special creation for various reasons, which he will masterfully elaborate on. Please sit back, relax, and enjoy the ride.

MG: Hi Lee, thank you for joining us today. I know you have been quite busy these last few weeks, with more exciting ones just on the horizon. So, why don’t we start out with something easy, like telling us something about you?

Hmmm… what to say??

I live in Melbourne (Australia) with my two cats—Mina and Bram (some folks reading might get the connection…), and a newly established tropical fish tank which sits on my office desk.

I was born in Melbourne, and although we moved away for a long time (to Western Australia)—I feel very much at home there. My recent visit to London reminded me a great deal of Melbourne, only on a larger scale.

I guess I am a little unusual in the scheme of ‘classical musicians’ in that I spent a lot of years working in rock and pop music as a record producer and a rock singer. I think that having worked in this area of the industry taught me a lot about communication and humility, and also—most interestingly—taught me a very visceral approach to making music.

MG: You found me on Facebook a few years ago, and what positively struck me was that, before deciding to begin our work together as a music-production team, you wanted to have a video chat to get to know each other. This made us bond in a way that I had not experienced before in the professional world. Please tell us how important it is for you to build a personal relationship as a ground on which to found a professional one.

A great friend of mine once said: “if you’re not a good hang, the music making will be rubbish”. In other words—relationships are EVERYTHING.

My scores are precious to me—and even though music notation is flawed ‘technology’—feeling comfortable with the people I’m working with is essential.

I try to establish relationships with everyone I work with, and take an interest in them as personally, with the intention of establishing and maintaining contact on a long-term basis.

My life is about my work, as much as my work is about my life—so it stands to reason the relationships in my life come out of the connections I make through my work. As a flow on, it’s my belief that putting the human needs first ensures professional needs are met in the best way. It’s not a strategy, simply the idea of mutual benefit in all things.

MG: As a composer of the younger generation, you are well aware of how badly the industry has axed the budget for new commissions. This, in turn, influenced the way composers can (or cannot) afford to hire a personal engraver. From the onset of our collaboration, you had the idea of budgeting, which I still today consider a stroke of genius. Would you mind elaborating on this, on how this helped you bring your music to a higher presentation level, and on whether this had a positive outcome during performances?

I think people will pay for what they feel has value.

The fact you were open to discussing how to budget your work ensured that I had access to your skillset and product in a way I could manage inside of commission fees. I think of the investment in much the same way I think of an investment into an excellent recording—it is not about recouping an expense or a cost, or to create a profit, but to ensure the work is put into the world in the best possible way.

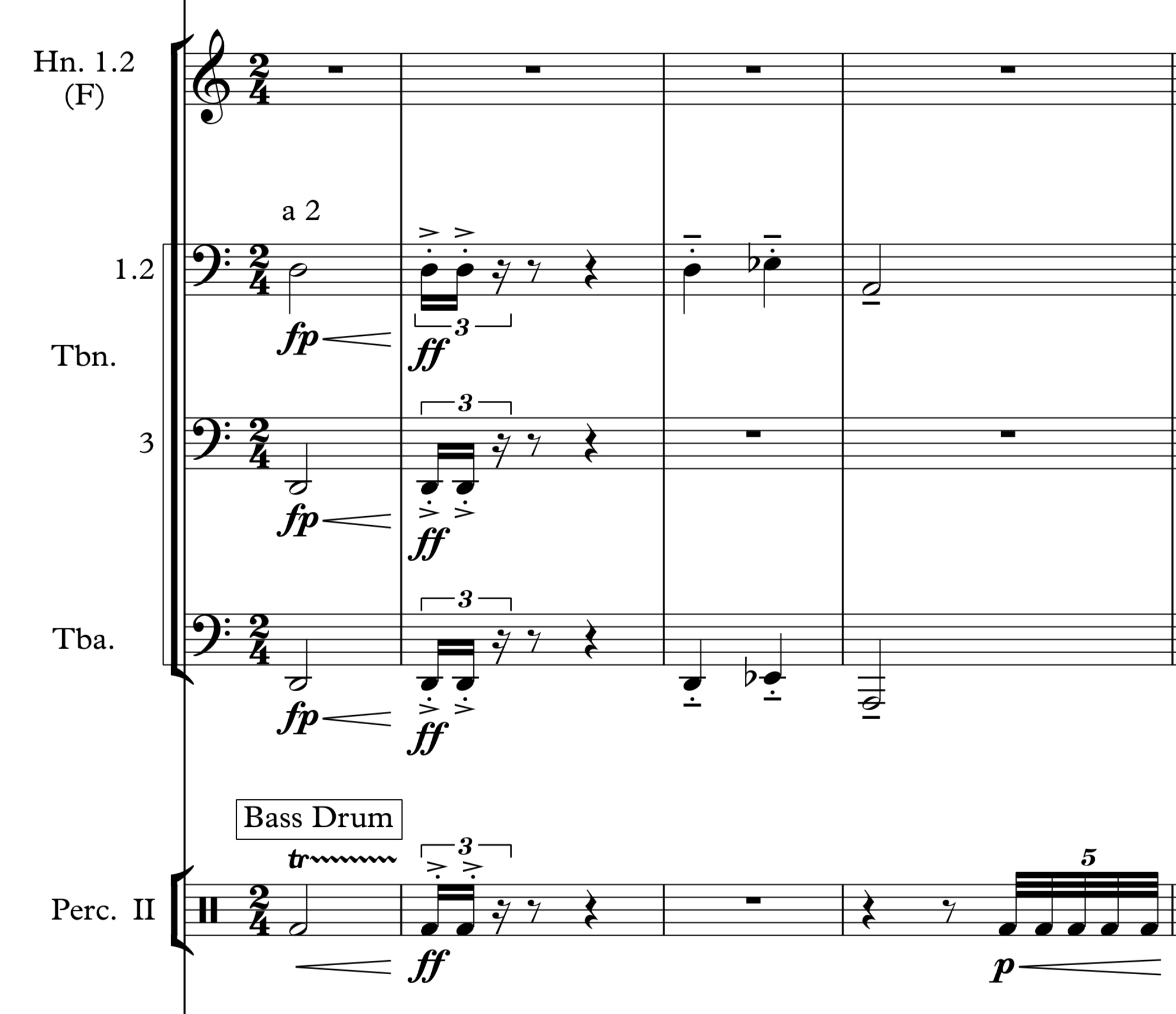

Some of our earliest discussions were to do with the visual affect of a score and how first impressions are made based on what a score (or part) looks like. Given all the hurdles, a new work faces by its very nature—the last thing you want to do is put a musician off with a messy manuscript.

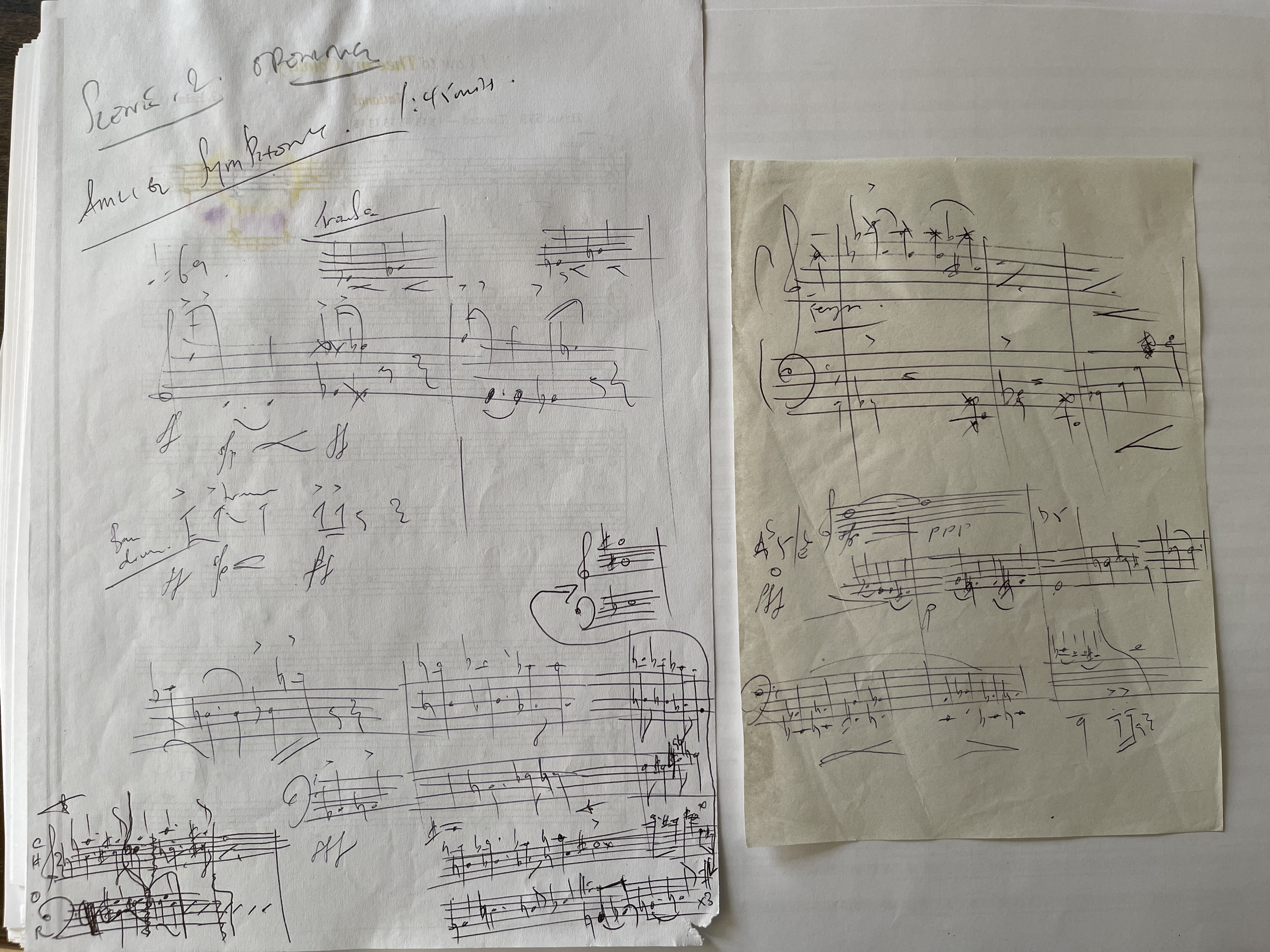

I work by hand—in fact, my first artistic expression as a small child was drawing, and it’s no coincidence I continue to write my scores by hand. It’s more personal. There appears to be a visceral connection to the imagined spirit of a piece of music and the way it’s written down. I think this a hugely important consideration when it comes to preparing a score for publication or distribution, and I wanted to find an ‘artist’ who shared the same outlook, or at least understood it.

Notation software is useful in creating ‘clean’ drafts to work on, and I will continue to work on top of those printouts by hand until I’m done drafting.

The other benefit (for me) working with you (in particular), and aside from your visual artistry—is that you have taken on what I would describe as an editorial/proofreading role (in addition to engraving and layout) which has proven to be especially helpful.

I work instinctively and (as a consequence) often very fast—(to mitigate the fact I can overthink things)—and having someone with such an eagle eye means I can rest assured there will be no stone left unturned.

It’s the final check and balance; half science, half art.

I know that each piece you engrave will be subject to a level of scrutiny, almost like automated quality control—automated for me at least!

In the end—I know that I’m not the only person who has considered what has gone into a work before it goes off into the world. Despite the fact that creating anything is so personal, it is surprising how beneficial it is to have a third-party perspective.

MG: Let’s delve deeper now. Please describe your compositional process, your inspiration, and what drives you as a composer. You once told me you want to build new repertoire. As I once told you, I believe your music sounds (and tastes, more on food later!) new, and yet familiar, daring, and yet comforting. Please guide us through what your creed as a classical music composer is.

I am very pleased with that summary, thank you!

I have always said the greatest masters of our craft never invented anything; what they did do however—was innovating, and that’s the trick.

To reject the fundamentals of music in lieu of experimentation, or invention—has its time and place I suppose—but it never made any sense to me in terms of my objective: to create repertoire and to contribute to the lineage and tradition of music that influenced and inspired me.

I don’t like the idea of creating ‘new pieces’—this concept feels like every new work is its own unique universe; it encourages the toxic habit many musicians have of over-hyping and obsessing with ‘world premieres’ which many collect like scalps for their CVs, as opposed to simply supporting the work of living composers by programming their music regularly AND repeatedly.

Composers need commissions to make a living—of course, but just as important (if not more important) is to have our works played repeatedly so they can become known, and their true value determined.

I like to programme my works next to ‘traditional’ or ‘standard’ repertoire where possible, and one of the best compliments I ever received was from a critic (in Italy) who heard my String Trio played between Beethoven and Schubert and remarked how “the new work was beautiful, and gave one a sense that it belonged there”.

I have developed what I consider to be a fluent musical language, and I can work very quickly with it; a sense of melody/harmony and structure that I have come to grips with in terms of those fundamental elements having become tools for my own expression. It’s not an invented language at all, it is—at its core—tonalism, and it draws on centuries’ established notions of the emotional affect of the diatonic system. Pushing and pulling, stretching and squeezing—seeing where the emotional and expressive potential of those tonalistic tropes can be tested and exploited for expressive and communicative purposes.

I don’t believe it’s an audiences’ responsibility to learn the laws of my ‘sound-world’ simply to understand what I’m saying; I think that type of attitude is an excuse for self-indulgence. My intention has always been to create work that people can use to express themselves with (and through), be they listeners OR musicians. None of that is to say that audiences and musicians don’t also have their own responsibilities—the art of active listening is the audience’s share of the load—but there have been a number of schools of thinking amongst creatives in the last 50–80 years which seem to have at their core a kind of nihilistic narcissism. Those artists subscribing to that outlook—most ironically—then complain that audiences don’t ‘understand them’ properly or aren’t prepared to take the time to decipher their work. Why should an audience? Isn’t it enough that they’re listening at all?

I aim to create music that is familiar enough to invite a listener in in the first instance, but unique enough to keep them listening after.

I was 9 years old when I heard Beethoven’s 5th, and from that moment I knew that that was what I wanted to do. Beethoven is perhaps the greatest innovator we have seen in our art; he really was the perfect storm in terms of timing along the trajectory of western musical development and what he contributed to the lexicon, as well as the personal circumstances which allowed for his output and its nature. That’s a longer discussion, however, and needless to say, he is by far the most significant influence of mine.

Then there are the usual suspects—Mozart, Bach and Handel; and later I was always impressed by Penderecki and Schnittke (even though I HATED Schnittke’s music when I first heard it in my early teens). I consider Bartok to be the most ‘modern’ sounding composer (despite the avant-garde which followed him), and I think Brahms is wonderful and misunderstood. More recently have been discovering the genius of Britten.

Outside that—and it’s impossible to ever give back something you have heard—I am definitely influenced by pop artists such as Paul Simon, Bruce Springsteen and Jimmy Webb; not to mention an Australian singer named John Farnham—who will always be a hero of mine.

I have several colleagues who find this confusing, but there is a workload in creating anything that has an impact on another human being, and all of these Artists have that (at least) in common.

MG: I know you write your music by hand—this is the Way!—and then copy it into a notational software before giving it to me for polishing. Could you describe what your expectations from working with a music engraver are? What do you feel has been improved by working together, and what would you ask if you could change only one thing?

My personal expectations are perhaps different to others for some of the reasons I have outlined above, i.e., that I began my creative life drawing and therefore think the visual impact of a score is extremely important. I am aware however that there are many who don’t think it matters at all—and whilst I can’t necessarily say they’re wrong, I don’t agree.

When I hand over a score to a musician, the common response is often—“it looks beautiful”—and this immediately gives the work credibility. It establishes a positive and collaborative mindset with the musician, as opposed to a combative one. Having a new work, laid out beautifully, gives the work an undeniable advantage.

As far as working with you personally—I think (for me) knowing that you are there to ‘pick up my mistakes’ or (at least) hold me to account for what I’m signing off on—means I can ascribe the total of my focus to the compositional content, knowing that the presentation and layout will be handled expertly. I can stay ‘down in the trenches’ with the music for longer, and that’s important.

When I was a student, and for years afterwards—I would have to make an entire additional effort simply to copy out the score and parts by hand. Working with you has to a large extent returned this time to me so that I can better spend it negotiating with inspiration!

MG: Now, let’s get to the meat—food again, I know, just wait a bit more! Let’s talk about your opera Zarqa. I still recall all the mystery surrounding this project, and how everything got settled in front of a pasta dish! Please tell us what you can share about the opera, especially why is this something unique?

The best things are decided around plates of pasta, no??

I think we can touch on the main points which make this project quite remarkable;

- Zarqa is the first western opera to be sung in Arabic (there have been other Operas sung in Arabic, but they are not strictly western ‘grand’ opera, and perhaps fall into a ‘folkloristic’ category)—for one;

- Second—it is the first grand opera to be produced in Saudi Arabia, and it will open an Opera House built back in the 1970s which has NEVER had an Opera performed in it;

- and Third—it is the flagship project of the newly established Ministry of Culture in KSA, which is spearheading the Kingdom’s Vision 2030 in regard to cultural and social change and development.

This project is designed to take aspects of Arabic culture to the West through an art form the West can understand, and consequently encourage a dialogue between the two worlds which aims to foster more cross-cultural collaboration.

It’s potentially historic, and it’s an incredible honour to be involved.

It is also (remarkably) a feminist piece.

Each character in some way represents an archetype of human nature, yet it is the female protagonists which carry the admirable traits of wisdom, virtue, and innocence.

Dame Sarah Connolly is performing the title role of Zarqa, and we have an absolutely stellar cast of voices from all over the world—including an Australian singer—Amelia Wawrzon, and of course, several Saudi vocalists and countless onstage extras performing acting and dancing roles.

The production is directed by Daniele Finzi Pasca—a true superstar of the stage—and I have to say the visual aspects of this are quite breathtaking. I have high hopes for it.

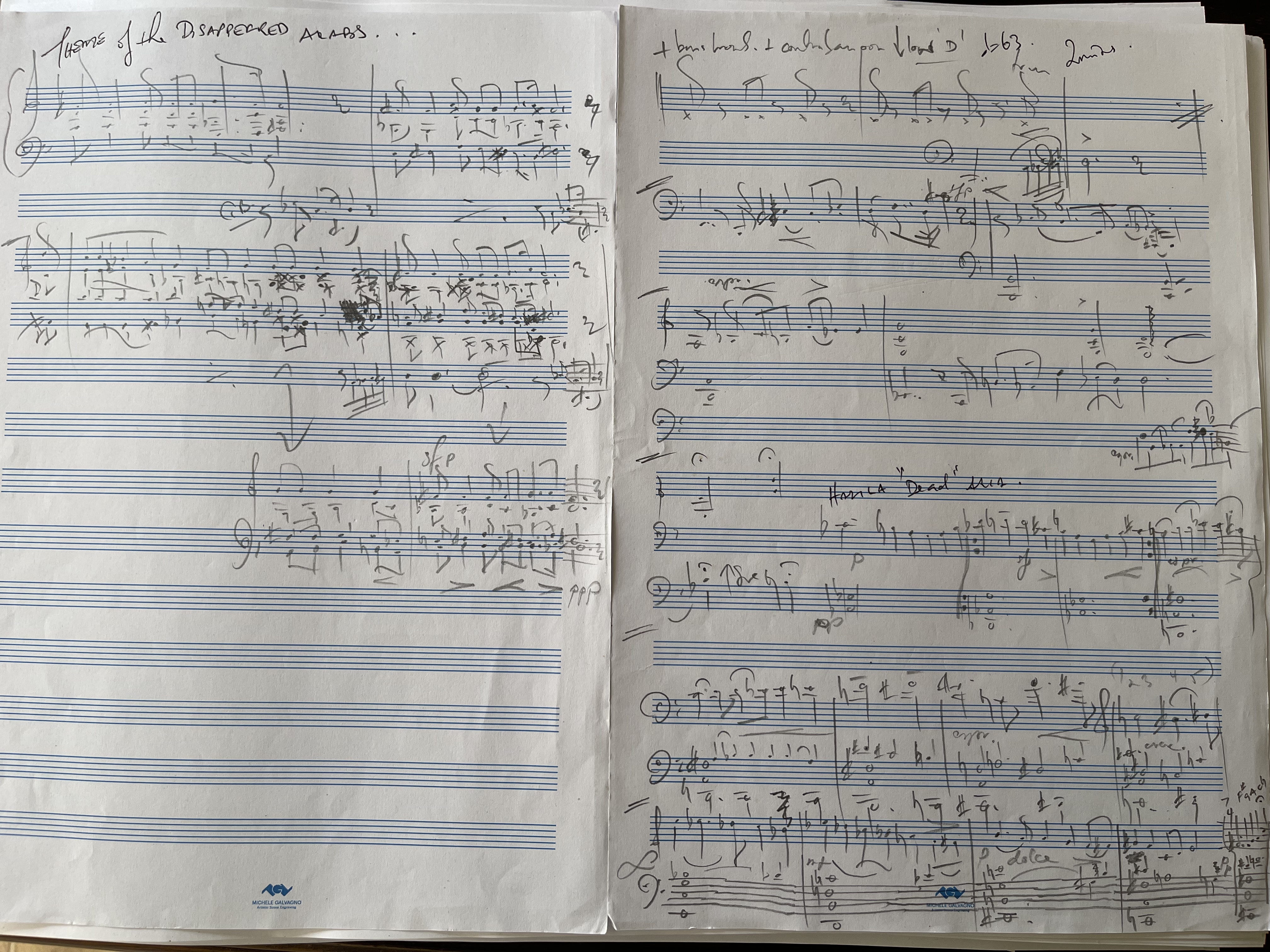

MG: I’m sure you recognise this excerpt:

I’m not the alone in the team thinking this to be the signature interval of the opera. Can you please elaborate more on this?

Ha! King Amliq—the GIANT!

Interesting that you should highlight this motif; as I did a bit of deep dive on it during our London Presentation to the press. Here’s some of what I said:

The three note motif: D — Eb — A contains three intervals related to three modes (or scales). The first; D — Eb (a minor 2nd) is the first two notes of the Phrygian scale—and I would suggest is the interval that characterises this scale, the second two notes; Eb — A (a diminished 5th) form the typifying interval of the major locrian scale, and the final interval A — D (a perfect 4th/5th) represent the dominant to tonic notes of the harmonic minor scale, as well as being the root notes of a perfect cadence.

All three scales are scales used heavily in music from the Arabian Peninsula, and the perfect cadence is one of the most easily recognisable devices in western music.

So what we have here—incumbent within this three note motif (D — Eb — A)—is the representation of three of the most commonly used scales in Arabic music, and a perfect cadence from the west.

Now—was I thinking about any of this when I was composing this music? That’s another question…

My idea of how best to take in an influence from Arabic music was certainly not to be academic, but to be instinctive. I immersed myself in traditional music from the region for months before I began work on the score, and (as a composer) I am generally cognisant of what is going on ‘under the hood’ of almost any music I hear—so it’s not to say I wasn’t aware of patterns and similarities which would emerge and that I could identify intellectually—only to say that I wasn’t dogmatically adopting those elements when it finally came to composing the work.

I did find (interestingly enough) that many of the characterising intervals within Arabic music are intervals I often use within my own vernacular, or musical language—intervals like the minor 2nd/minor 9th and the diminished 5th.

My concept of consonance and dissonance though is perhaps different to others, and so the kind of devices which serve those purposes within my musical language seemed to have a synergy with what I was hearing in Arabic music.

Perhaps it was divine providence?

It has been remarked already how the score sounds unmistakably ‘Bradshaw’ but with a flavour and spirit of Arabic music and influence which is difficult to pin down. And this was my objective, to be honest. I feared an academic approach would yield what some might describe as an ‘orientalist’ outcome, and what I really wanted was a genuine influence on an original score, not a westernised pastiche of clichés.

I give a great deal of credit to my Artistic Director and longtime collaborator—Ivan Vukčević—who counselled me early in the composing process to ‘write what you write. Do not compromise’. This was a critical moment which gave me freedom to create without fear of some kind of committee process, like one might experience working on a film score. Zarqa—in the end—is really a very pure creation in that sense.

MG: Finally, food! I recall how, last year, you wrote to me asking whether I could be in Torino on the next day. How was it finally meeting in person, taking strolls in the medieval city, and enjoying a few specialties together?

Torino is a beautiful city, but in truth it’s difficult to find an ugly city in Italy, so! I only wish we had another day or so to discuss more things!

To meet in person finally was great—of course, and it was the perfect time to do that before embarking on such a gigantic project like Zarqa. You don’t make it through a work of that size and scope without some cuts and bruises, but the strong survive, and these things galvanise a team in my view.

I’d like to think that, for both of our practises (respectively)—that Zarqa has lifted us up to a new and higher standard of achievement.

MG: I know you have been tirelessly producing more music after the opera. Is there something you can share about that or about your future projects?

I did take a bit of time after the Opera… creative hangover, maybe. Zarqa was created in such a vacuum that in hindsight, I feel like I was in a frenzy or a daze. Only recently I went back through all my manuscripts and notes—and I know that I discarded more working materials than I kept—and I have six inches of A3 paper in a tray of materials that eventually became our Opera.

I did (about halfway through composing Zarqa) produce an Oboe Quartet called “The Language of Trees”—which was performed at our Chamber Music Series in Melbourne, but after I had delivered the Zarqa score in late January 2023, it wasn’t until August that I composed anything else.

I did work on some revisions of my Piano Trio from 1999/2018, as well producing a viola/organ version and a cello/piano version of the viola/piano sonata from 2007.

Finally, I wrote a solo cello suite for Australian cellist Josephine Vains (after Bach) and to be performed intertwined with a selection of movements from the six suites; then after my trip to US in September I wrote a number of Trios for different forces (2 x Piano trios—one where the cello part is interchangeable with a bass clarinet; a trio for Horn, Double bass and piano; and a trio for Flute, Viola, and Guitar). In December, I worked on a big piece for Cello and Percussion called “Radiance (or The Black Sonata)” for the Australian National Academy.

I also composed a Quartetto Aria for Zarqa to buffer out the transition from Scene 2 to Scene 3 while I was travelling through the US in September. It was an awful trip, and I wished the entire time that I was at home in Australia—but at least it yielded the Quartetto, so that’s something.

It looks like I will spend a little time later in the year going back to my ‘old life’ as a rock singer, finally issuing an Album (or two) or material that has been waiting to be released for some years now.

Just before COVID-19 we lost a bandmate and great friend—one of Australia’s best guitarists, Stuart Fraser—to lung cancer, and it didn’t seem right to release those recordings until now. I know that he would want us to put the record out, so we’re going to do that. I’m sure that that may surprise some!

MG: Thank you so much for taking the time to chat today, Lee. It’s been a pleasure to have you on the blog, and I can’t wait to see and taste all the music you have in store for us. If people wanted to get in touch with you, listen to more of your music, and to follow you, where should they look? Finally, if there is a single piece of you they should listen, what should it be?

They can always make contact through my website.

Right now, I have to say that Zarqa is the best thing I have ever done, but unless you come to the premiere season in Riyadh you won’t be able to hear it—not yet at any rate!

So, my Album “The Ties That Bind” includes a selection of material that I think summarise my voice—at least within the forces of chamber music; the String Trio “Trigon” is perhaps a good starting point, and the Sarabande for cello; and if one appreciates those then perhaps the next step might be the Concerto for Two before working your way up to the Duo Sonata for viola and cello, or the Rhapsody for viola solo.

Baiba Skride plays the solo “Via Crucis” wonderfully well, though—and it’s not too long, so maybe that is the single best work to try before seeing if you want to order a second course!

MG: That’s great! Thank you, Lee!

I really enjoyed learning about how you collaborated together, thank you for sharing the process. I wish you both the best of luck in your future endeavours. Best wishes Charlotte

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Charlotte. I will contact you in the coming days via email about your inquiry.

LikeLike